The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (66 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

Between 912 and 945, the Fatimid caliph fails to overthrow the Abbasids, the emir of Cordoba becomes a caliph, and the Buyids in the east take control of Baghdad

D

OWN IN

E

GYPT

, the Fatimid caliph al-Mahdi set his eyes on Baghdad. He did not claim to be

a

caliph; he claimed to be the

only

rightful caliph, bearer of holy authority over all Muslims worldwide.

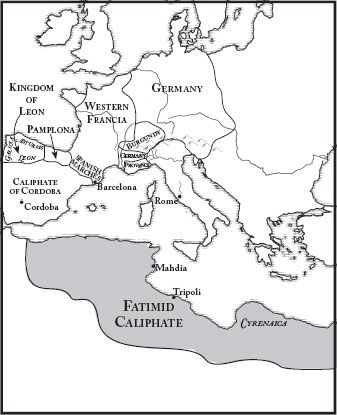

But unless he could work this claim out in victory against the Abbasids, his pretensions would remain merely local. He had established a new capital city on the coast, Mahdia; he had the support of the North African Berbers, who had long resented Abbasid rule; but to lay hold of full authority, he needed to push his way eastward into the Abbasid holdings.

1

In 912, he proclaimed his son to be his co-ruler and his successor, giving the nineteen-year-old boy the title

al-Qaim bi-amr Allah,

“The One Who Executes God’s Command.” He then put al-Qaim at the head of an army, which would proceed to the east in order to wipe out the Abbasid control of Egypt.

2

But al-Qaim and his men had a long way to travel, through North African territory unfriendly to the Fatimid cause, before Egypt would even appear on the horizon. In 913 young al-Qaim (aided by two experienced generals lent to him by his father) forced Tripoli to surrender after a six-month siege. The following year, the Fatimid armies used Tripoli as a base to march even farther east along the coast into Cyrenaica, the far edge of Abbasid control. By August, Fatimid soldiers were streaming into Alexandria. In November, al-Qaim himself arrived in the city, and the mosques of Alexandria were ordered to honor the Shi’a rulers, not the Abbasids of Baghdad, in their prayers.

3

The court at Baghdad was nominally ruled by the nineteen-year-old caliph al-Muqtadir, but unlike his young Fatimid rival, al-Muqtadir had no real power. His vizier and generals planned to respond to the Fatimid threat without his help. They knew that the Fatimid armies intended to march all the way to Baghdad (al-Qaim had sent to his father an exultant letter, promising that he would spread Fatimid power all the way to the Tigris and Euphrates), and so they put the skilled eunuch soldier Mu’nis at the head of the resistance.

67.1: The Fatimids and Cordoba

Mu’nis marched towards Egypt at the head of the Abbasid forces in 915. The Fatimid expansion east collapsed as quickly as it had expanded. Al-Qaim’s men had fought beyond their strength; faced with a determined Abbasid resistance (the treasury at Baghdad was opened, and Mu’nis was given two million dirhams, the equivalent of six and half tons of silver, to fund his counterattack), al-Qaim quickly retreated and gave up his Egyptian holdings. Al-Mahdi built himself a fleet of warships and launched a second attack in 920. This time, the return Abbasid assault all but destroyed his new navy.

4

The Fatimid power was not yet a major threat to Baghdad, but al-Mahdi’s rebellion had an unintended consequence. Over in Cordoba, the emir Abdullah had died in 912, to be succeeded by his grandson, twenty-one-year-old Abd ar-Rahman III; and ar-Rahman III saw in the Fatimid rebellion a possible solution for his own difficulties.

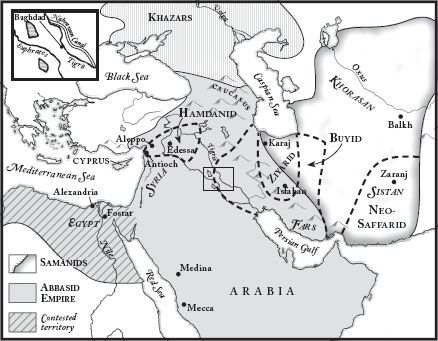

67.2: Competitors of the Samanids

The Spanish Marches, the mountainous lands between the Emirate of Cordoba and the Frankish border, had been occupied since the end of Charlemagne’s reign by independent warlords who were propped up by the power of the Frankish kings. These warlords, who often bore the title of count, had grown increasingly independent and aggressive, and their power threatened the emirate’s lands in the northeast; the count of Barcelona had proved to be particularly troublesome. To the south, an elusive rebel named Umar ibn-Hafsun had been leading guerilla attacks on Cordoban forces for almost thirty years; Abdullah had been unable to either catch or drive him out.

5

Directly to the north, the Christian kingdoms of Pamplona and Asturias were thriving in an alarming fashion, doing their best to reconquer the Muslim-held land in al-Andalus. The king of Asturias, Alfonso III, had managed to draw together the territories of Asturias, Leon, and Galicia into a triple-sized Christian realm known as the Kingdom of Leon. He had also married a Pamplona princess, creating a solid wall of Christian alliance against Cordoban power.

And just across the mouth of the Mediterranean, on the southern side of the water, al-Mahdi had declared himself caliph, rightful ruler of all Muslims, including ar-Rahman III himself. Ar-Rahman had come to power at the eye of a hurricane.

Unsurprisingly, he spent the first fifteen years of his rule fighting. He launched yearly attacks against the southern rebel ibn-Hafsun until the revolt finally disintegrated; he fought against the soldiers of the Spanish Marches; he campaigned against the Kingdom of Leon.

6

Against the caliphate of North Africa, he took an even more aggressive stance. He would not swear loyalty—but neither would he continue to swear loyalty to the distant caliph in Baghdad. The emir of Cordoba had no more reason to give even surface allegiance to any fictional leader of the Muslim world.

Instead, he aspired to become a leader himself. On January 16, 929, ar-Rahman declared himself to be caliph of Cordoba, Commander of the Believers, Defender of the Religion of God. Unlike the Fatimid caliph, ar-Rahman was not claiming to be the one true caliph, supplanter of the Abbasid rule. Instead, he was declaring his complete and total independence from both the Abbasid and Fatimid claims. Ar-Rahman would rule on his own account, claiming his authority from his Umayyad ancestors; he had placed himself outside of the Fatimid-Abbasid conflict.

7

Now there were three caliphates in the Muslim world, with three caliphs claiming imperial power. And the Abbasid caliph at Baghdad was the weakest by far.

8

T

O THE EAST OF

B

AGHDAD

, the emir of the Samanids was acting with almost complete independence from Baghdad. Samanid merchants travelled all the way up the Volga river to trade with the Khazars and the Rus, and the Samanid realm had grown increasingly wealthy, increasingly strong. In 911, the Samanid emir, Ahmad, had captured the remaining strongholds of the rival eastern dynasty, the Saffarids. This had extended Samanid control across the east.

9

Ahmad was now the ruler of a de facto Muslim kingdom, and he decided to make Arabic the official language of his Samanid court. This was quite in line with the myth that he was acting as a lieutenant for the caliph in Baghdad, but he had underestimated the national feeling of the Persian speakers in the old Saffarid lands. They didn’t want to be folded into yet another Arab-dominated Muslim kingdom; they wanted their own Persian lands back again. Ahmad found himself putting down continual rebellions in the old Saffarid province of Sistan, centered around the city of Zaranj. He had just begun to triumph over the revolts when, in 914, he was assassinated in his own tent by his servants.

His son Nasr became the Samanid emir in his place. But Nasr was eight years old, and power lay in the hands of his regent, the vizier al-Jaihani. At this, Abbasid officers in Sistan rebelled and claimed Sistan, making it into their own little country and finding a Saffarid family member to install as their puppet-emir. This faux-Saffarid domain would last until 963.

Not too many years later, the Samanids also lost control of their territory near the Caspian Sea, when a soldier named Mardaviz al-Ziyar helped the local Samanid officials to seize power and then took it himself. His little emirate, the Ziyarid dynasty, expanded quickly to cover land south of the Caspian Sea, as far as the city of Isfahan. It also gave birth to yet another rival dynasty: in 932, one of al-Ziyar’s own officials, Ali ibn Buya, seized the city of Karaj and used it as a base to battle south into Fars.

Now the Samanids had spawned three rival lines in the east: the neo-Saffarids in Sistan, the Ziyarids south of the Caspian Sea, and the Buyids battling the Ziyarids for territory. At the same time, the governors of Aleppo, all members of the Hamdanid family, were establishing their own independent domain.

*

This patchwork rivalry did not remain all Muslim. Counting on local feeling to help keep him in power, Mardaviz al-Ziyar announced himself the restorer of the old Persian empire, a follower of Zoroastrianism, undoer of the Muslim conquest. He was probably insane (he claimed to be a reincarnation of Solomon, son of King David, although it is difficult to see how this made him Persian), but he was a powerful and charismatic personality, and the willingness of the natives to support him demonstrates just how shallow the conversion to Islam had been in many parts of the empire. He was so successful that the competing emir Ali ibn Buya, governing his own land farther south, followed his lead and began to call himself not “emir” but “shah” of his newly conquered territory, using the old Persian honorific.

10

Over the next decades, the dynasties of the east would form confederacies, break apart, and rejoin, each clan hoping to check the power of the others, each governing family limited by the ambitions of its neighbors. And as the east disintegrated, the Abbasid caliphate slid further into irrelevance.

In 932, the figurehead caliph al-Muqtadir, who had remained alive because he had been content to be powerless, was deposed by his brother al-Qahir, who ruled as caliph for two years. Unlike al-Muqtadir, al-Qahir tried to exercise power, which ended badly. Only two years after becoming caliph, he was deposed and blinded by his Turkish courtiers and soldiers. He spent the last years of his life begging on the streets of Baghdad. His nephew al-Radi, son of al-Muqtadir, became puppet-caliph instead.

Like his father, al-Radi ruled with no authority. But until this point, the Abbasid caliphs had continued to carry out the ritual responsibilities of their office: they sat in council, led Friday prayers in Baghdad, appeared at assemblies, gave alms to the poor. Al-Radi too walked through these motions, but he would be the last to do so. By 936, al-Radi—twenty-nine years old, caliph for barely two years—realized there was no way for the caliph to continue on as head of the Abbasid state. The breaking away of the eastern territories meant that the tax base of the empire had been ruined. He could not pay his soldiers; he could barely supply his own court; he certainly could not fight off any real challenges to his power.

11

His most powerful general, Muhammad ibn Ra’iq, had taken control of the lands southeast of Baghdad and was refusing to send the taxes he collected there on to the capital. Now Muhammad ibn Ra’iq offered the caliph a solution. If al-Radi would agree to recognize ibn Ra’iq with the title

amir ul-umara

, “Commander of Commanders,” the general would come into Baghdad with his handpicked band of Turkish soldiers, bring his collected tax revenues with him, and take over the administration of the empire—allowing al-Radi to remain caliph in name.

With no other options left to him, al-Radi finally agreed. He awarded ibn Ra’iq the title and gave him what little power the caliph still had. Ibn Ra’iq arrived in Baghdad with his loyal Turks, disbanded the existing Baghdad army, and put the current vizier to death.

12

It was the end of the Abbasid caliphate in all but name. From now on the Commander of Commanders would control the remains of the empire, while the Abbasid caliph was left with little more than the title.

Far from bringing peace, ibn Ra’iq set off a struggle in Baghdad for control of the caliphate. His tenure as Commander of Commanders came close to destroying what was left of the empire. In his battles with his rivals, he even ordered the breaching of the Nahrawan Canal, the man-made water system that stretched two hundred miles across the salty dry plains just east of Baghdad; this temporarily blocked the advance of one of his challengers, but it also destroyed the irrigation that kept the plains populated. The farmers who had sent their produce to Baghdad began to move away; their farms withered.

13