The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (61 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

Theological conviction can founder in the face of defeat though, and Alfred kept his place in the pantheon of divinely appointed rulers by emerging from the Athelney marshes with a strong and desperate army behind him. In the late spring of 878, he met the Great Army of the Vikings at the Wessex town of Edington and triumphed. “Fighting fiercely, with a compact shield-wall,” Asser writes, “he persevered resolutely for a long time; at length he gained the victory through God’s will. He destroyed the Vikings with great slaughter, and pursued those who fled.”

14

After the battle at Edington, the Viking chief Guthrum agreed not only to sign a treaty with Alfred but also to convert to Christianity. He brought thirty of his strongest warriors with him, and all of them were baptized on the same day. Afterwards, they retreated to their own land. The agreement signed by Alfred and Guthrum, the Treaty of Wedmore, divided England in two. The south and southwest remained in Anglo-Saxon hands; Alfred ruled the southern lands, and placed the rule of the shrunken Mercian kingdom in the hands of his daughter and son-in-law, who governed it under his supervision. Guthrum and his Vikings were awarded independent control of Northumbria, the eastern coast, and the eastern half of Mercia.

Alfred’s victory at Edington may have been decisive, but the Vikings had suffered greater defeats without surrender. The truth was that the Viking troops, once raiders and havoc-makers, had now been in England for almost fifteen years. They had rooted themselves into the English countryside, married Anglo-Saxon women, fathered children, planted farms, and lost a little of their piratical edge. They had begun to feel like natives, not invaders; they were ready to start new lives; and they were willing to accept the new faith if that would give them their farms and families. And Alfred’s men were no less anxious to go back to their fields, their wives, and their lives.

In the years after Wedmore, Alfred was forced to put down several Viking attempts to seize more land for themselves. But the division of England into two kingdoms, the Anglo-Saxons and the Danelaw, would stand. The Treaty of Wedmore was a compromise, but it gave everyone what they wanted. Guthrum and the Viking warlords got a new home; Alfred was able to lay claim to the greatest Anglo-Saxon kingdom yet, a southern realm he could pass on to his son Edward; and Alfred’s followers, the exhausted and war-beaten Anglo-Saxons of Wessex and Mercia, were finally permitted to return to their old, barely remembered lives.

It was for this that Alfred was remembered with gratitude: he was both conqueror and peacemaker. “Renowned, warlike, victorious, the zealous supporter of widows, orphans, and the poor,” the twelfth-century historian John of Worcester concluded, “most dear to his people, gracious to all…. [H]e awaits the garment of blessed immortality and the glory of the resurrection with the just.”

15

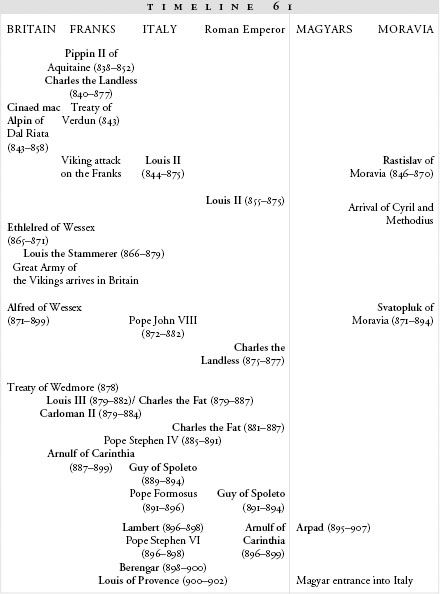

Between 875 and 899, Charles the Landless buys the title “Emperor of the Romans,” Charles the Fat inherits the entire empire by chance, and the Magyars arrive in northern Italy

I

N

875, C

HARLES THE

L

ANDLESS

became emperor of the Romans by the most direct method possible. He offered Pope John VIII a huge bribe; the chroniclers agree that John crowned him, on Christmas Day, in exchange for

dona, pecunia, multa et pretiosa munera

.

1

This infuriated Louis the German, who thought that the title should have come to him. Their older brother Lothair had died in 855, leaving his son Louis II the Younger as king of Italy and emperor of the Romans; Louis II had died earlier in 875, and Louis the German, the oldest Frankish king left, had expected to be the next emperor. He was now sixty-nine years old; he had seen the title passed to brother and nephew, and he wanted the imperium for himself.

Apparently it hadn’t occurred to him to pay for it. But now that the coronation was over, all he could do was take revenge. While Charles the Landless was still in Rome, Louis the German stormed into his western Frankish lands, destroying and burning in fury. Charles hurried back home, but before the brothers could face off, Louis the German died. A lifetime of frustrated ambition had come to a sudden end.

Shortly afterward, Charles the Landless died of sudden illness; his son and heir, Louis the Stammerer, barely survived him by two years. The complicated mass of Frankish kingdoms devolved onto the surviving heirs: Louis the German’s two sons Carloman and Louis the Younger (Louis III) divided the eastern Frankish realms between them, but when Carloman had a stroke, his lands passed on to his younger brother Charles the Fat, who was already ruling in Italy. The western Frankish kingdom was ruled jointly by Charles the Landless’s two grandsons.

The Frankish kings negotiated and jousted for position. In 881, the pope decided to crown Charles the Fat of Italy as the emperor of the Romans. This had less to do with Charles (who was not much of a warrior) than with the fact that he was technically in control of Italy. The pope was worried that the Papal States might come under attack from one of his neighbors: Guy, the ambitious duke of Spoleto. If the pope were to invest any other Frankish king with the title of emperor, Charles might not allow him to come into Italy in defense of the pope—even though that was the purpose of the title.

Charles accepted the title of emperor, but after his coronation he never returned to southern Italy again, and certainly never bothered to help the Papal States against Guy of Spoleto’s raids. But despite his disinterest, Charles the Fat—originally a younger brother with no chance of inheriting anything for himself—was soon not only emperor of the Romans, but the most powerful monarch in the west. In 882, two of the Frankish kings died of separate natural causes. In 884, the third was killed while hunting. All of these realms, one at a time, were added to the kingdom of the remaining legitimate heir: Charles the Fat. Chance and fate had managed to reunite the old empire and title of Charlemagne under a single king—with the sole exception of the territory of Provence, which had rebelled and declared itself independent.

*

What Louis the German had failed to do in a lifetime of fighting, negotiating, and sweating blood, Charles the Fat had gained without lifting a finger.

2

But gaining and keeping were two different things, and Charles the Fat—weak and inept, with no legitimate son or heir and no plans for ruling his enormous new empire—almost immediately ran into trouble. In 885, the year after the entire empire had fallen under his rule, he began to have increased trouble with Vikings. They had been raiding his lands on a regular basis, but he had generally managed to buy them off with silver and (occasionally) hostages. Now the invasions grew more severe. Not all of the Great Army of the Vikings had settled in England; some of the warriors, not liking the idea of farming, had made their way back to the mainland to resume their life of raiding. They had also branched out from raiding by ship. Now, they were apt to land horses on the coasts and thunder across the countryside on horseback, raiding and killing in a much wider swath. “The Northmen do not cease capturing and killing the Christian people,” lamented a Frankish monk,

destroying churches, demolishing fortifications, and burning towns. Everywhere, there are only corpses of priests, laymen, whether noble or not, women, young people, suckling babes. There is no road, there is no place, where the ground is not strewn with corpses.

3

Charles the Fat seemed entirely unable to stop the raids. He assembled an army that marched against the Vikings at the city of Louvain, where the Franks were badly defeated. Victorious, the Vikings captured the city of Rouen, then organized a massive invasion up the Seine: seven hundred ships sailed up to the walls of Paris and laid siege to the city.

4

Charles, who was far away from Paris at the time, sent an army, which failed to lift the siege. In desperation, he offered the Vikings seven hundred pounds of silver and winter quarters in Burgundy in exchange for their retreat.

The Vikings agreed to the bargain and lifted the siege of Paris. But Charles the Fat had lost whatever sympathy his people still had for him. They were furious: if he were going to hand over their tax money instead of driving the invaders away, why hadn’t he done so at the beginning of the siege and spared them a great deal of trouble? The Burgundians, particularly annoyed by the cavalier offer of their homeland, revolted. Charles’s nephew, Arnulf of Carinthia, raised an army, and in 887 he marched into the Frankish territory to remove his uncle by force.

In the face of all this hostility, Charles the Fat agreed to give up his titles as king and emperor. His willingness to surrender may have had something to do with his health; he had been suffering from a serious condition in his skull, even undergoing trepanning in an attempt to relieve his pain. In January of 888, just months after his abdication, Charles the Fat died.

The empire disintegrated into even smaller pieces than before, and a scramble for the title of emperor of the Romans began. Arnulf of Carinthia became the king of Eastern Francia; two Italian noblemen, Berengar of Friuli and Guy of Spoleto (the same duke of Spoleto who had been threatening to trouble the Papal States), began to quarrel over the right to become king of Italy; five different noblemen claimed other parts of the empire.

*

“As though bereft of a legitimate heir,” writes the chronicler Regino of Prum, “the kingdoms that had obeyed him no longer waited for a ruler given by nature, but each chose to create for itself a king from its own innards. This situation sparked tremendous warring.”

5

In such chaos, the pope, Stephen V, protected his own interests. He declared Guy of Spoleto king of Italy and crowned him, in 891, as emperor. This bore the earmarks of a deal: the papal sanction and the title of emperor, in exchange for Guy’s agreeing to leave the Papal States alone. It was, perhaps, not exactly what Charlemagne had meant when he declared that the emperor of the Romans had the responsibility of protecting the pope.

After only three years as emperor of the Romans, Guy of Spoleto died unexpectedly, intending his fourteen-year-old son Lambert to succeed him as king of Italy: “an elegant youth,” writes the historian Liudprand of Cremona, “and, though still an adolescent, quite warlike.” Berengar of Friuli, who had not given up hope of becoming king of Italy, was still causing trouble in the north; he at once advanced to the city of Pavia and declared himself rival king.

6

In the midst of all this, the pope—Stephen V’s successor, Formosus—sent a message to Arnulf of Carinthia, now king of Eastern Francia, and promised him the title of emperor if he would come down and restore peace. To Formosus’s mind, his predecessor had overstepped himself by granting the honor to a random Italian warrior rather than to a king from the family of Charlemagne. Arnulf of Carinthia, Carolingian by birth, was the obvious candidate for the position.

Arnulf agreed and, in 896, finished the long journey to Rome at the head of his army. Lambert, hearing of the Frankish king’s approach, had fled to his father’s old homeland, Spoleto; Arnulf allowed Formosus to declare him not only king of Eastern Francia but also king of Italy and emperor of the Romans, and then began to march towards Spoleto to deal with Lambert.

But on the short journey between Rome and Spoleto, he suffered from a stroke, which partly paralyzed him. Abruptly, he gave up the plan to defeat Lambert and returned home.

Lambert emerged from Spoleto and reclaimed the title “King of Italy,” but before he could get to Rome and punish Formosus, the pope died. Lambert barely allowed this to stop him. With adolescent outrage, he ordered Formosus’s successor, Stephen VI, to open Formosus’s casket. The dead pope was dressed in vestments and set behind a table, and Stephen VI convened a synod of churchmen to condemn and defrock the body. “Once these things were done,” writes Liudprand of Cremona, “he ordered the corpse, stripped of its holy vestments and with three fingers cut off, to be tossed into the Tiber.” The fingers were those with which Formosus had blessed the people of Rome. The synod itself was labelled, later, as the

Synodus Horrenda

, the “Trial of the Cadaver.”

7

With his feelings relieved, Lambert marched back up north and made a deal with Berengar: Lambert would rule the southern lands of Italy, Berengar could govern the north, and Lambert would seal the deal by marrying Berengar’s daughter, Gisela. Berengar agreed. He probably had no intention of keeping to the terms of the deal, but he had no chance to violate it. Just months later, at the age of eighteen, Lambert broke his neck. Liudprand of Cremona wrote, in the first draft of his history, that Lambert was out hunting boars and fell off his horse; later, he revised his draft to add, “There is another account which seems to me more likely.” In this second version of events, Lambert had been murdered by a young man from Milan whose father had been executed, and the assassin had then arranged the body so that a hunting accident would be suspected instead.

8

However it happened, the death allowed Berengar to announce himself as king of all Italy. But although he had finally grasped his crown, an evil coincidence was about to remove it.

61.1: The Magyars

To his north, a storm was gathering. Once again a warrior had united separate tribes into a nascent nation: this time, the tribes were Finno-Ugrian, like the peoples among whom the Rus had settled. The warrior’s name was Arpad, and he had created an alliance in which he was the first king. “Before this Arpad, they had never, at any time, had any other prince,” wrote the Byzantine emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus, in his history of the Magyars.

9

Under Arpad, soldiers of the Magyar alliance began to move westward. Around 895, they had arrived at the edge of Moravia; in 898 they attacked Venice but then retreated. But in 899, just as Berengar claimed the Iron Crown of the Lombards, they advanced towards the north of Italy. They had been encouraged to do so; Arnulf of Carinthia, back in Eastern Francia, had offered them clothing and money if they would direct their energies towards northern Italy. Arnulf had been forced to give up the conquest of Italy, but he had not given up hope of removing his competitors.

10

Berengar and his army fought back, but the Magyars were fresh, hungry, and hard to defeat. They were also experts at guerilla warfare, and for the next year, they sacked Italian towns and retreated before Berengar’s men could catch up with them. Berengar began to lose the support of the Italian noblemen who had been willing to support his rule; if he couldn’t get rid of the Magyars, what use was he?

Led by a northern Italian duke named Adalbert, whose lands had been hit hard by the Magyars, the noblemen invited a minor Carolingian prince, Louis of Provence (great-great-great-grandson of Charlemagne on his mother’s side), to come into Italy and take up the Iron Crown. Berengar put up a token fight, but his army had shrunk, while Louis of Provence’s supporters were increasing in number. Berengar was forced to flee from northern Italy, leaving the Iron Crown in the hands of his rival and the Magyars victorious in his wake.