The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (64 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

The Bulgarians won the day, chasing the remnants of the Byzantine army southwards. Leo Phocas barely escaped. As for the admiral Romanos Lecapenus, he ordered his ships to pull up anchor and retreated back into the safety of the Black Sea as soon as he realized the battle was lost.

Leo Phocas tried to make another stand right outside Constantinople, but the Bulgarians massacred his remaining men a second time. By the time he managed to struggle back inside the city walls, Romanos Lecapenus was already there. He had sailed straight for the city, and now his fleet was anchored in the water nearby.

Before Leo Phocas could explain his defeat, Romanos Lecapenus struck. He invited the city officials to board his flagship to discuss strategy and then locked them in the hold, after which he marched into the city and removed Zoe and all of her supporters. He was practically unopposed; he had managed to escape blame for the defeat, which had fallen squarely on Zoe and her lover Phocas.

14

Romanos took charge of the council of regents, promising safety and deliverance. Leo Phocas, recognizing trouble, discreetly removed himself from Zoe’s offers of marriage and retreated to Chrysopolis. No one tried to keep him from leaving.

By April of 919, Romanos had gained so much popular support that he decided to try for the crown itself. He sent Zoe to a convent and convinced the council of regents to name him Constantine’s second-in-command. He then arranged for the marriage of his own daughter, nine-year-old Elena, to the thirteen-year-old Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus. As both father-in-law and vice emperor, he had only one more step to ascend to the throne itself.

It proved to be a short step. The patriarch, old Nicholas Mystikos, saw Romanos as a welcome replacement for Constantine VII, who remained illegitimate in the unbending old man’s eyes. Mystikos agreed to crown Romanos as Romanos I, co-emperor of Byzantium, and young Constantine was again in the shadow of a senior emperor. He would stay there for the next quarter century. The court loyalty that had allowed him to assume the crown had shifted to the able older man, pushing Constantine to the side.

When Leo Phocas objected strenuously to all of this from his distant retreat, Romanos sent two men to arrest him. They overstepped their authority and blinded him. Romanos declared himself to be extremely distressed by this turn of events.

15

Meanwhile Simeon I of Bulgaria had regrouped and was again fighting his way towards Constantinople. He had already been to its walls, more than once, and knew that the city was all but unconquerable with a ground force. His only hope of taking it was with ships, and Bulgaria had no navy. He would have to borrow one; so he sent an embassy to the Fatimid caliph al-Mahdi, who had now extended his control eastward to the old city of Carthage, and asked al-Mahdi to make a formal alliance with him.

Al-Mahdi agreed; the alliance undoubtedly struck him as a prudent pre-emptive strike. Unfortunately for Simeon, on the way back from North Africa his ambassadors were taken prisoner by Byzantine soldiers and sent to Constantinople. Romanos then sent an offer of his own to the Fatimid caliph: if al-Mahdi would become his ally, rather than Simeon’s, he would pay tribute and guarantee a peace.

On consideration, Romanos decided that he’d better make sure that neither Islamic empire attacked him, and so also sent offers of peace to Baghdad.

Both caliphs accepted Romanos’s terms. Deprived of his ally, Simeon asked for parley instead. Romanos agreed to meet with him, and careful preparations were made; both sides remembered the Byzantine attack on Simeon’s predecessor Krum. The two kings sent hostages to each other, and a wooden platform with a wall across its center was built in the waters of the Golden Horn. On September 9, 924, Simeon rode up onto the platform from land, on horseback; Romanos sailed up to it on the royal ship; and the two men looked each other in the eye across the wall.

16

Simeon’s ambitions had been thwarted by canny politics and alliances, the same canny politics and alliances that had brought Romanos to the throne. But, face to face with his enemy, Romanos used the language of faith, not the language of war. His speech to Simeon, as historian Steven Runciman points out, is recorded word for word in various chronicles, suggesting that an official record was made of his words. He said,

I have heard that you are a religious man and a devoted Christian; but I do not see your acts harmonizing with your words…. If then you are a true Christian, as we believe, cease from your unjust slaughter and shedding the blood of the guiltless, and make peace with us Christians—since you claim to be a Christian—and do not desire to stain Christian hands with the blood of fellow-Christians…. Welcome peace, love concord, that you yourself may live a peaceful, bloodless and untroubled life, and that Christians may end their woes and cease destroying Christians. For it is a sin to take up arms against fellow-believers.

17

Coming from a man who had just made peace with two different caliphs in order to thwart his fellow-believer, this was a bit thick. Nevertheless, Simeon was taken aback. He agreed to a peace in exchange for restoration of the annual tribute, and returned back home.

In 927, Simeon had a heart attack and died. He was succeeded by his son Peter, who made a lightning-quick destructive invasion of the Byzantine territory in Macedonia and then retreated and offered to make peace. Romanos, taking his cue from the destruction Peter had just wrought, agreed. As part of the treaty, Peter I married Romanos’s granddaughter.

Even more important, Romanos, yielding the point that had begun the whole fight, recognized him as emperor. The Bulgarian king had risen to the same status as the ruler of Constantinople.

Between 902 and 911, Berengar blinds the emperor of the Romans and takes Italy for himself, and Charles the Simple gives part of Western Francia to the Vikings

I

N

902,

THE

I

TALIAN NOBLEMAN

Berengar finally won back the Iron Crown of the Lombards. He defeated Louis of Provence, who held the triple titles “King of Provence,” “King of Italy,” and “Emperor of the Romans,” in battle. As part of his surrender, Louis promised Berengar that he would return to his homeland and would content himself with ruling Provence (as an independent king; he refused to swear allegiance to the king of the eastern Franks) and being emperor of the Romans; he would never enter Italy again.

This promise lasted only until 905, when Adalbert and the other Italian nobles invited Louis back again. Berengar, says Liudprand of Cremona, was “perceived to be tiresome,” which probably means that he was behaving in a more royal manner than they liked. The Italian nobility was accustomed to having a fair amount of independence, and Louis of Provence had been a hands-off ruler.

1

So Louis came back into Italy and set himself up with great ceremony in the city of Verona. He knew that Berengar would attack him again, but he had been guaranteed soldiers from the private armies of Adalbert and the others, and he was confident of victory.

He was a little taken aback, though, by the size of the private armies—and by the luxury in which Adalbert and the others lived. Tactlessly, he remarked to one of his generals that Adalbert seemed to aspire to royal splendor, and that only the lack of a royal title made Adalbert less than a king.

Adalbert’s wife overheard the conversation. It struck her as a veiled threat and she warned her husband that Louis of Provence might not prove quite as willing to let them go their own way as he had once been. Behind the scenes, as Louis set himself up for battle, the noblemen consulted, argued, and then agreed to withdraw their support quietly from Louis’s cause. Berengar, getting wind of the change, offered a substantial bribe if they would let him into Verona late at night while Louis was off guard.

They agreed, and while the unsuspecting emperor of the Romans slept, Berengar and his men crept into the city. Berengar’s guards found Louis and dragged him in front of Berengar, who snapped, “I let you go out of pity, when I captured you before, and you promised that you would never re-enter Italy. This time I will spare your life, but I will take your eyesight.”

2

His men then gouged out Louis’s eyes. Louis survived the operation, but now that he was mutilated and unable to function without help, he was forced to relinquish the title of emperor as well as the Iron Crown of Italy. He returned to Provence, where he lived almost twenty years. For the rest of his life, he was known as Louis the Blind.

3

Berengar, once more on the Italian throne, hoped to become emperor of the Romans in Louis’s place, but the pope made no motion to offer him the title. Berengar was not a Carolingian, and there was no guarantee that he would be king of the Italian territory for long.

*

Back up to the north, the kings who

were

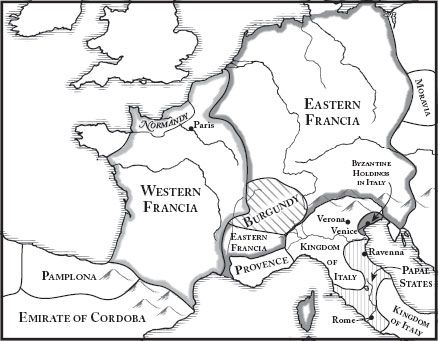

Carolingian were too preoccupied with their own difficulties to campaign for the title of emperor. The jumble of Frankish mini-kingdoms had begun to sort itself out as some of the minor players were conquered, or murdered, or simply fled. Arnulf of Carinthia had died right after hiring the Magyars to harass northern Italy and had been succeeded, as king of Eastern Francia, by his six-year-old son Louis the Child. The noblemen of Western Francia had elected Charles the Simple, grandson of Charles the Fat, to rule them. The upper part of Burgundy, which had rebelled when Charles the Fat offered it to the Vikings as a playground, remained independent under one of its own nobleman, Rudolf of Burgundy. Invading Magyars troubled the eastern Frankish lands, and Vikings harassed Charles the Simple in the west.

The Viking raids, brought temporarily under control by Charles the Landless’s fortified bridges, had once again intensified. In 911, Charles the Simple settled on a drastic solution to the Viking raids. He decided to give part of his land in Western Francia to Viking invaders, in a treaty that would guarantee protection for the rest of his realm.

He chose to negotiate this deal with a Viking chief who was already known to him: a man named Rollo who had already spent a good part of his adult life fighting in Western Francia. He had been a junior commander of the fleet that besieged Paris in 885, and had returned on a regular basis ever since: raiding, fighting, accepting payment, withdrawing, and then raiding again.

Charles the Simple offered Rollo a homeland of his own on the western coast and promised to make him ruler of it. In exchange, Rollo would have to agree to accept Christian baptism, to be loyal to the king of the Western Franks, and to fight against any other Viking invaders who might trouble Charles’s kingdom.

64.1: The Creation of Normandy

Rollo agreed to the deal. He picked Robert as his baptismal name, and the Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte transformed the Viking warrior into the first duke of Normandy. It also transformed him into Charles’s son-in-law; to seal the treaty, Robert of Normandy married Gisela, Charles the Simple’s daughter.

But seeds of trouble were visible, even at the ceremony that awarded Rollo his new land. One of the nearby bishops ordered Rollo to kiss the king’s foot, a common gesture of respect from a subordinate to the king. According to the contemporary

Gesta Normannorum Ducum

, Rollo at first refused. Then,

pressed by their prayers he eventually ordered one of his soldiers to kiss the king’s foot. This man promptly took it, lifted it to his lips, and pressed a kiss upon the foot while standing upright, so that the king fell over backwards. This resulted in a great roar of laughter and a mighty tumult among the people.

4

Having demonstrated his intention to remain independent, Rollo then cheerfully took all of his oaths. He would rule in Normandy for the next two decades, theoretically in subjection to the king of the Franks, but in reality doing exactly as he pleased.