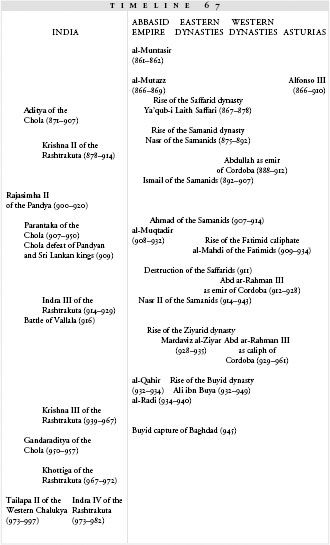

The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (67 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

And then ibn Ra’iq was overthrown, two years later, by one of his lieutenants, and three other Commanders of Commanders claimed and lost the position in short succession. Al-Radi died of illness in 940, and the struggling factions agreed to elect his brother to his position, but the man held no power—and would never observe even the forms of the caliphate.

To the north, the Buyids were on the move. They were battling their way towards the chaos and division of Baghdad. As they approached, the Abbasid puppet-caliph fled; the Turkish soldiers in the capital chose a new caliph, but his time was brief. In 945, the Buyid general Ahmad ibn Buya (brother of Ali) marched into Baghdad and claimed the title “Commander of Commanders” for himself.

The figurehead caliph was deposed and blinded. Ahmad ibn Buya allowed a new caliph to be elected but barred him from any participation in the government of the city. The Buyids were in control of the empire, and Baghdad had fallen under the rule of an upstart family, one that no longer required even the meaningless approval of a powerless caliphate to claim rule.

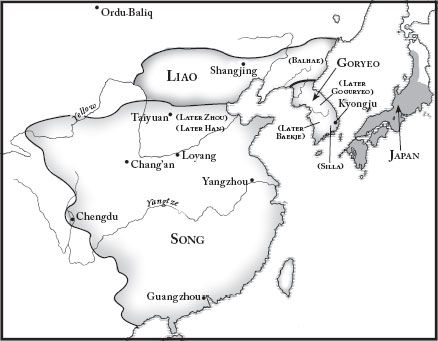

Between 918 and 979, the kingdoms of Goryeo, Liao, and the Song draw the shattered east back together

T

HREE KINGDOMS

now lay on the peninsula east of China, two of them in the hands of rebels who had managed to transform themselves into monarchs. The southwest lands were ruled by the bandit king Kyonhwon, who had named his realm Later Baekje; the north, by the naval officer Wang Kon.

*

Wang Kon, elevated to the throne of Later Goguryeo by court officials who had resented his predecessor’s tyranny, was particularly aware that the crown was only tentatively his. He did his best to erase the traces of past revolt, renaming his kingdom Goryeo, moving the capital city to Kaesong, and announcing himself to be the founder of a new royal dynasty. “Owing to your hearty support, I became king,” he told his people. “By joining together to correct laws, we can rejuvenate the country. Learning from past mistakes, we should look for solutions to problems in our immediate surroundings and recognize the mutual dependence of ruler and subject, realizing that our relations are like those of fish and water. The country will join in the celebration of the peace.”

1

This was a web of wishful thinking; there was no peace on the horizon. Kyonhwon of Later Baekje had not revolted in order to share the peninsula with other kings. Now that he had established his own kingdom, he aimed to wipe out his competitors.

However, Kyonhwon did not immediately invade Goryeo; he set his sights first on the tattered Sillan kingdom to his southeast. The alcoholic King Hyogong of Silla had died childless, and his successors—a series of short-lived royal relatives—were unable to mount a successful defense. The castle lords had no loyalty to the throne. Instead, they treatied with Kyonhwon of Later Baekje or Wang Kon of Goryeo (depending on whose army was closest) as though they were independent rulers.

2

Wang Kon did not immediately take advantage of the Sillan disintegration. His speech to his people had not been entirely untrue: he had glimpsed a truth that Kyonhwon was blind to. Silla, weary of war, was more likely to be won by friendship than by battle.

Kyonhwon, delighted by Wang Kon’s absence from the struggle, fought his way into Sillan territory. By 927, his armies had reached the capital city of Kyongju. The Sillan king of the moment, Gyeongae, could not hold the gates against him; Later Baekje’s soldiers flooded into the city, sacked and burned its buildings, killed civilians and defenders alike, and broke into the royal palace. King Gyeongae was murdered in his own banquet hall.

This gave Wang Kon the chance to play deliverer. “Kyonhwon, having an evil nature that nourished rebellion, killed the Silla king and oppressed the people,” the Goryeon statesman Choe Seung-no wrote. “Hearing this, T’aejo [Wang Kon’s royal title] wasted no time sending troops to punish the crime and finally restored order. Such was T’aejo; remembering his former king, restoring order, and halting a dangerous situation in this way.”

3

In fact, Wang Kon was now taking over by stealth. Once Kyonhwon had done the hard work of breaking down the capital city’s walls, Wang Kon sent his own army in, drove the Later Baekje forces out, and elevated a royal cousin named Gyeongsun to the Sillan throne. He married one of his daughters to Gyeongsun, garrisoned the capital city with Goryeon troops, and announced that he had rescued Silla.

4

Gyeongsun was, of course, a puppet-king. Wang Kon’s strategy, which placed both the government of Silla and the loyalty of its castle lords firmly into his hands, won him the great prize: rule of the entire peninsula. Kyonhwon tried to retake the Sillan land, but over the next nine years Wang Kon drove him steadily backwards. In 932, a deciding battle between the Later Baekje and Goryeo armies ended with the surrender of most of Kyonhwon’s troops. Kyonhwon himself kept on fighting, doggedly, with no more than a handful of soldiers still loyal to him. Finally, in 935, his sons turned against him and imprisoned him, taking the defense of the remaining Later Baekje territory into their own hands.

Once again, Wang Kon showed himself capable of playing a very deep game. First of all, he demanded the abdication of his Sillan son-in-law, the puppet-king Gyeongsun. The young man hurriedly obliged, and Wang Kon folded the remains of Silla into his own realm. He was now the only other king on the peninsula.

Then, some months later, Kyonhwon escaped from prison in Later Baekje. Most probably he had help from Wang Kon’s agents, because within weeks he was up in Goryeo, a prosperous slave-owner, living in peace with his old enemy. The slaves were a present from Wang Kon, a bribe intended to turn his one-time opponent into a friend. “T’aejo honored Kyonhwon,” the

Samguk sagi

records, “and gave him the South palace as an official residence. His position was made superior to those of the other officials…. [he was given] gold, silk, folding screens, bedding, forty male and female slaves each, and ten horses from the court stables.”

5

The bribe worked because Kyonhwon was furiously angry with his sons—and already ill with the cancer that would kill him. Not long after settling in Goryeo, he asked Wang Kon for an army: “It is my hope,” he told the king, “that you will enlist your divine troops to destroy the traitorous rebels, and then I can die with no regrets.”

Nothing could have pleased Wang Kon more. He dispatched his oldest son, the crown prince Mu, and his most trusted general to accompany Kyonhwon back into Later Baekje with ten thousand soldiers. He himself followed at the head of another strong division. The army of the rebellious sons was crushed; the three oldest brothers, the ringleaders, surrendered, and Wang Kon ordered them put to death. He ceremoniously gave the kingdom back to his old enemy. Just days later, Kyonhwon died of his illness, and Later Baekje fell into Wang Kon’s hands. All three kingdoms were now under a single crown.

6

“In the past,” Wang Kon told his people, in a set of injunctions intended to shape the future of his newly unified country, “we have always had a deep attachment for the ways of China, and all of our institutions have been modeled upon those of the Tang. But our country occupies a different geographical location and our people’s character is different from that of the Chinese. Hence there is no reason to strain ourselves unreasonably to copy the Chinese way.” Under Wang Kon, the country of the Koreans would take its shape. Silla had only been a foretaste of unification; after Wang Kon, the peninsula would remain a single nation for the next thousand years.

7

O

VER ON THE MAINLAND

, the northern nomads known as the Khitan still longed for Chinese ways.

The Khitan had now adopted a more settled existence under the warchief Abaoji, who had become their Great Khan in 907. Freed from the shadow of the Tang, the Khitan kingdom—like Goryeo—had the chance to mature according to its own lights.

But Wang Kon’s Goryeo had hundreds of years of tradition to build on, and the Khitan had nothing but the very recent nomadic past. Abaoji, distancing himself from the uncertain and unsettled life of the nomads, grasped onto the customs of the extinct Tang. By 918, he had given himself the Chinese royal name “Celestial Emperor Taizu,” built himself a new Tang-style capital city at Shangjing, and had named his oldest son to be crown prince and heir. Blood succession was not a Khitan tradition; the nomads had always chosen their leaders for their skill in battle. But a settled kingdom with a settled capital needed a settled royal line.

8

Just before his death in 926, the new Celestial Emperor began to fight his way towards Balhae, the kingdom north of Goryeo. The Khitan armies invaded Balhae’s land, sending its people flooding down into Goryeo for refuge. Just as the Balhae capital fell, Taizu died—leaving his people with a newly expanded territory, an inexperienced crown prince, and an unfamiliar set of royal traditions.

His redoubtable wife kept the Khitan empire from falling apart.

In the tenth-century chronicles she is called “Shu-lu shih,” which merely means “of the Shu-lu clan.” But her skills as a leader were as great as her husband’s. The dead Celestial Emperor had appointed their oldest son as heir, but Shu-lu shih preferred her second son, Deguang. She assembled the tribal leaders, mounted both boys on their horses, and then told them that Deguang deserved to be the new emperor. Then she added, “I love these two sons of mine equally and cannot decide between them. Grasp the bridle of him who seems to you the worthier!”

9

The tribal leaders, taking the unsubtle hint, chose Deguang, who from this point on ruled (along with his mother) as the emperor Taizong; Shu-lu shih had successfully reimposed on her husband’s royal line the old Khitan succession of the worthiest. The erstwhile crown prince, the older son Bei, took Balhae as his own (renaming it Dongdan) and ruled it as an independent kingdom.

Meanwhile, Shu-lu shih developed a useful way of making sure that her wishes became law. Whenever a Khitan leader opposed her, she sent the leader to her husband’s tomb in order to ask his advice—at which point the guards who watched over the dead emperor’s final resting place did away with the visitor. Together with her prime minister, Han Yanhui, she continued the Celestial Emperor’s mission of turning the Khitan horde into a Chinese kingdom.

10

In 930, the displaced older Bei fell out with his brother, the Celestial Emperor Taizong. Taizong sent his own son to govern Dongdan; Bei fled into the chaos of China. By 936, Taizong had simply annexed Dongdan and had given his empire a new name to go along with its new customs: the old Khitan realm became the kingdom of the Liao. The northeast now lay under the rule of two strong and unified kingdoms, Goryeo on the peninsula and the Liao empire across the north.

Meanwhile a bewildering assortment of states and kingdoms rose and fell south of the Liao. Not until 960—with the Liao stable under the reign of Taizong’s son Liao Muzong, and Goryeo prospering under the rule of Wang Kon’s son Gwangjong—did one of the would-be royal dynasties of China manage to root itself firmly into the former Tang landscape.

This dynasty grew out of the Later Zhou state, which had occupied the land around Chang’an and the lower curve of the Yellow river from 951 until 960. Nine years was a fairly average survival time for a ruling dynasty during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period; the Later Zhou ruler had overthrown the Later Han dynasty, which had ruled in the same area for all of three years, and the Later Han itself followed on the heels of the Later Jin (eleven years), the Later Tang (thirteen years), and the Later Liang (sixteen years), all occupying more or less the same territory.

In 960, the Later Zhou dynasty went the way of its predecessors. Its emperor (the second in nine years) died, leaving only a baby as heir and a young empress as regent. The officers of the Later Zhou army disliked the empress, who had no experience with war. Afraid that the army would lose its pre-eminent place in Northern Zhou society, they rebelled and declared their favorite general to be emperor, founder of yet another new dynasty: Emperor Taizu of the Song.

There was no particular reason why Taizu’s dynasty should be more successful than any of the ones that had come before. Yet he seemed to have an unusually strong sense of what needed to be done to restore the China of the past. “From the moment that he grasped the reins of power,” one of his chroniclers notes, “his mind seemed to be absorbed with one great thought: to restore the unity of the empire.”

11

Taizu, like the rulers before him, had taken his crown by force; but like the great Chinese rulers of the past, he managed to weave a story around himself that lent him the sheen of heavenly approval. “Immediately after he was born,” the chronicler tells us, “the sky was filled with reddish clouds that overhung the house where the child was, and for three days the dwelling was pervaded by a most fragrant odour. People at the time remarked to each other that all this portended a great future for the boy.”

12

After-the-fact prophecy had always worked well for Chinese emperors who could back up the prophecies with victories in battle, and Song Taizu was a good fighter.

He had also learned from the past. The army had made him emperor and could dethrone him just as easily. As soon as he was firmly on the throne, he summoned all of his officers to a banquet and made them an offer: if they would renounce their ranks, give up all military authority, and retire to the countryside, he would give them handsome severance pay and turn over to them “the best lands and most delightful dwelling-places,” where they could pass their lives “in pleasure and peace.”

13

This unexpected act seems to have broken the cycle of revolt that had brought one dynasty after another into power. Song Taizu reformed his army from the ground up and then led them in a series of campaigns against the surrounding states. There were six states to his south and one to his north, but just beyond the northern state (the Northern Han) lay the enormous Liao. Song Taizu decided that he first would tend to the south, where no powerful enemy lurked behind the divided landscape.