The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (63 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

But his rule lasted only three months. Tadahira ordered a price put on his head; the heavenly sovereign didn’t have a standing army, but he had plenty of money. Two other great landowners, one of them a Fujiwara and the other a member of Masakado’s own clan, banded together to fight against the New Emperor (and claim the reward). Three months after Masakado had crowned himself, his two opponents descended on the northern border of his captured territory with their own private troops.

Masakado’s army, like all the other armies in Japan, was in flux; the men who served him were not full-time soldiers, and they tended to come and go so that they could take care of their private lives. At the moment of attack, it had temporarily shrunk to about four hundred men. The tiny force was wiped out, and Masakado was killed. “His horse forgot how to gallop as the wind in flight,” says the

Shomonki

, the contemporary history of his revolt, “and the man lost his martial skills. Struck by an arrow from the gods, in the end the New Emperor perished alone.”

16

Masakado’s armed revolt was the unruly provincial version of the Fujiwara grab for power in the center of the kingdom. It was less successful than the sophisticated political maneuvering in Heian, but it was a foretaste of things to come. For the next century, the Fujiwara would continue to dominate, in their hereditary semi-legal dictatorship; but their power would not go unchallenged. The heavenly sovereign had been slowly boxed into a smaller and smaller space, and outside that space the aristocratic families of Japan fought for power with increasing ferocity.

Between 886 and 927, Leo the Wise defies the patriarch of Constantinople, the Bulgarian king demands the title of emperor, and Romanos Lecapenus explains that Christians should not fight wars

L

EO

VI,

LEGAL SON OF

B

ASIL

I, was twenty when he became sole emperor of Constantinople. Almost at once, he began to earn himself the nickname “Leo Sophos,” or “Leo the Wise.” This title did not necessarily suggest enormous skill in government; it meant something more like “Leo the Bookish.” Leo read widely, had a prodigious memory, and occupied his evenings by writing military manuals, revising legal codes, composing hymns and poems, and preparing sermons, which he delivered on feast days and special occasions.

1

He was not the first emperor to preach sermons—his predecessor Leo III had given a whole series of anti-icon homilies—but Leo the Wise had his hands in church affairs up to the elbows. The theologian Arethas of Caesarea called him

theosophos

, “wise in the things of God,” which may be a code phrase for “meddler in sacred things.” He had barely come to the throne when he decided to replace the patriarch, the senior churchman in Constantinople, with his own nineteen-year-old brother, Stephen, and after Stephen’s death he appointed the next two patriarchs on his own authority as well.

2

The second of these patriarchs, the monk Nicholas Mystikos, proved less malleable than Leo the Wise intended. By 901, Leo had to face the unpleasant truth that the succession to the throne was in danger. At nearly forty, he had married three times, but he had not managed to father a son; in fact, he had been forced to crown his brother Alexander as co-emperor and heir.

He had not given up hope, though. When his third wife died in 901, Leo tried to marry again, this time choosing his mistress, Zoe Karbonopsina, “Zoe the Black-Eyed.”

At this the patriarch Nicholas Mystikos balked. Even marrying three times was not exactly legal; an arcane bit of church doctrine said that while it was perfectly acceptable to marry again if your spouse died, you should only do it once. The patriarch had squinted at the third marriage, but he’d have had to close his eyes for the fourth, and this he was unwilling to do.

Leo put up with this through the birth of Zoe’s first baby, a girl. She became pregnant again at the beginning of 905; when she went into labor, Leo moved her into the porphyry-walled palace chamber where, by tradition, empresses gave birth to royal heirs. To be born in the Purple Chamber meant that the court had admitted you into its center; and the court of Constantinople was much more powerful, as a whole, than any single emperor. “Emperors might and did come and go,” writes the historian Arnold Toynbee, “able adventurers might and did oust an ephemeral dynasty, but the Court lived on.” Venerated by the court, the emperors of Constantinople were also hostage to the court’s goodwill, and an emperor’s power was only as great as the loyalty of his ministers and officers.

3

Leo’s court was loyal enough to support his quest for an heir, so Zoe delivered in the purple room, surrounded by the traditional attendants. Much to Leo’s relief, her baby was a boy. Reaching for every strategy that might help legitimize his new son, the emperor gave him the hallowed royal name “Constantine.”

4

Both the name and the birth in the Purple Chamber were props to the baby’s legitimacy, but to ensure his position beyond challenge, Leo still needed to marry his son’s mother. He suggested again to the patriarch that he should wed for a fourth time. Again the patriarch refused. Leo,

theosophos

that he was, decided that patriarchal permission was unnecessary, and married Zoe anyway, in a lavish public ceremony that infuriated the senior churchmen of Constantinople. “The mother was introduced into the palace, just like an emperor’s wife,” Nicholas Mystikos later wrote, in a letter to Rome, “and the very crown was set on the woman’s head…. [T]he archpriestly and priestly body was in uproar, as though the whole faith had been subverted.”

5

Despite his objections to the marriage, Nicholas Mystikos was essentially the emperor’s man. But the loud yells of outrage from the other churchmen in Constantinople forced him to uphold the church’s authority. Since Leo had defied the church, Nicholas Mystikos barred him, reluctantly, from entering the churches of his own city.

This was unacceptable to Leo. In 907, he sent his soldiers to remove (by force) and exile not only Nicholas but also the whole tier of priests who had objected to Zoe’s installation as empress. Then, when Constantine reached the age of six, Leo crowned him as co-emperor. He gave the little boy the royal name “Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus,” meaning “purple-born,” to remind everyone who approached the new emperor that the court had supported Constantine’s right to inherit.

He intended to make the succession as secure as possible before he died, because Byzantium was under hard pressure from the outside. For at least two centuries, the Islamic armies had been the greatest threat to Constantinople’s safety. Now, the Abbasids were preoccupied with their own troubles, and the main locus of the threat had shifted west.

The Bulgarian king Boris, who had presided over his country’s formal conversion to Christianity, had been distant but cordial, and had even sent his son Simeon to be educated in Constantinople. But Simeon, once on the Bulgarian throne, turned into an enemy.

*

Like Leo the Wise, Simeon was a reader: Nicholas Mystikos described him as a man whose “love of knowledge led him to reread the books of the ancients,” and his reading had fired his imagination. He wanted to turn Bulgaria into a great empire like the empires of old, and while Leo was absorbed by his marital troubles, Simeon was able to advance Bulgarian forces all the way to the walls of Constantinople. In 904, Leo had been forced to make a treaty giving the entire north of the Greek peninsula to Bulgaria—which made Simeon the emperor over almost all of the Slavic tribes in the lands now known as the Balkans.

6

This had lifted one western threat, but another was approaching. In 906, the same year that Constantine Porphyrogenitus was confirmed as co-emperor, the Rus also pushed their way to the gates of Constantinople.

The Rus had been growing in strength since their conversion. Their own accounts tell us that Rurik, the legendary Viking warrior who settled at Novgorod, had steadily spread his power among the surrounding peoples, and that when he died in 879, he left both his kingdom and the guardianship of his young son to another Rus nobleman, Oleg of Novgorod. Oleg took power for himself and three years later moved the center of his power to Kiev.

Since this same Oleg apparently was still alive and active seventy years later, most historians suspect that “Oleg” is a title rather than a personal name. The story reflects a general spread of Rus power under their warrior leaders; by the end of the ninth century, the Rus had forced the neighboring Slavic tribes to pay them tribute. The

Russian Primary Chronicle

lists a multitude of subjected peoples, including the eastern Slavic tribe of the Drevlians, who were forced to supply troops for the 906 attack on Constantinople—a total of two thousand ships, stuffed with men from twelve different nations. According to the colorful but unreliable

Chronicle

, the Rus made “wheels which they attached to the ships, and when the wind was favorable, they spread the sails and bore down upon the city from the open country. When the Greeks beheld this, they were afraid.”

7

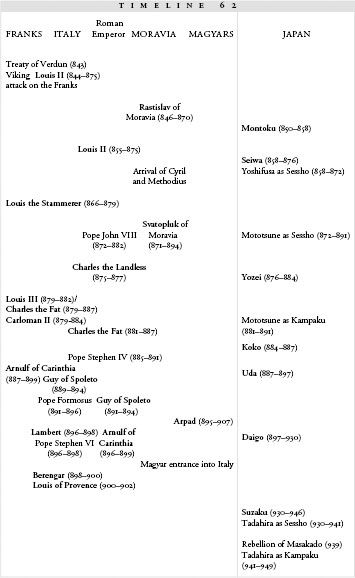

63.1: Loss of the Balkans

Whatever terrified them, the people of Constantinople agreed to pay a huge tribute so that the Rus would retreat. A second treaty in 911 established a fragile peace, but the future looked grim to Leo. He died in 912, predicting on his deathbed that the empire would totter in the hands of his heirs.

8

With Leo’s death, his brother became senior emperor. Alexander, now forty-two, had been a crowned emperor without power for thirty-three years. He had spent most of his adult life drinking, hunting, and waiting for his brother to die, and his new authority went to his head. He was no fool; he dismissed Leo’s court officers and recalled instead old Nicholas Mystikos, who was not likely to support any effort of the improperly born Constantine VII to usurp his uncle’s authority. But then Alexander immediately announced that Constantinople would not pay the Bulgarian king Simeon I the yearly tribute Leo had promised.

9

This defiance simply begged Simeon to descend on Byzantium and prove that he was no paper king. Simeon I took up the dare and doubled it; the historian Leo the Deacon writes that he sent a message to Constantinople, demanding that the new emperor acknowledge that Simeon too was an emperor,

basileus

of the Bulgarian people and so equal in rank to Alexander himself.

10

Alexander, of course, refused.

Leo the Deacon is no fan of non-Greeks—using the ancient and dismissive term for Bulgarians, he chalks Simeon’s demand up to “customary Scythian madness”—but in fact Simeon now had been not only cheated of his money but also insulted, and so could justify to his own people the risk of besieging the great city itself. As he began to march towards Constantinople, Alexander, having started the fight, died; he had a stroke in the middle of a post-dinner game of ball on horseback (a sort of medieval polo), living only long enough to appoint Nicholas Mystikos as his young nephew’s head regent. His death left the city in turmoil, ruled by a child and facing an approaching Bulgarian army led by a determined and insulted warrior king.

The decision of how to deal with Simeon I was thus left to Constantine VII’s council of regents, now headed by old Nicholas Mystikos. The patriarch was still smarting over Leo’s decision to overrule his judgment in favor of the pope’s, back when Constantine was a baby. Should Nicholas Mystikos admit without reservation that Constantine VII was legitimate and therefore the rightful ruler of Constantinople, he would also be admitting that the bishop of Rome had been right and he had been wrong—not a likely scenario. When Simeon I appeared outside the walls of Constantinople, Nicholas Mystikos found himself in an awkward position: supporting the rule of an emperor he thoroughly believed to be illegitimate.

He agreed to admit Simeon to the city for a parley and proposed a peace treaty. Byzantium would pay tribute to the Bulgarians, Constantine VII would agree to take one of Simeon’s daughters as his wife, and he himself, the patriarch of Constantinople, would crown Simeon as emperor of the Bulgarians:

basileus

, bearing the same authority (although only over his own people) as the emperor of Byzantium.

Undoubtedly Nicholas Mystikos would have been much more reluctant to take this route had he not firmly believed that Constantinople

had

no legitimate emperor. There was no harm in allowing Simeon I to take the title of emperor, since no one (in his view) actually

held

it at that particular moment.

11

Constantine’s mother, Zoe, was naturally appalled by the proposal, as were a good many of the soldiers and courtiers at Constantinople. Once Simeon was safely out of the gates, Zoe led a palace revolt, threw Nicholas Mystikos out of the palace (he remained regent, but she warned him to mind the business of the church and stay out of hers), and took control of the council. She then cancelled the entire peace treaty with Simeon.

In revenge, Simeon embarked on a series of raids and attacks. He began to capture cities on the border between the two countries with increasing and worrying frequency. By 917, it was clear that the Byzantine army would have to launch a major strike against the Bulgarians.

Constantine VII was still only eleven, so the planning of the strike lay in Zoe’s hands. She had two commanders to make use of: Leo Phocas, general of the Byzantine ground forces, and Romanos Lecapenus, admiral of the Byzantine navy. Romanos Lecapenus was a skilled officer, but he was also the son of a peasant and did not cut much of a figure in Byzantine society; Phocas, who was generally thought by army men to be a commander of limited talent, was a handsome aristocrat. But Liudprand of Cremona tells that he “ardently desired to be made father of the emperor,” and Zoe decided to entrust the attack to him.

12

He marched his army north along the Black Sea coast to meet Simeon I and the Bulgarian army at Anchialus, on the shores of the Black Sea, while Romanos Lecapenus lay off the shore with his fleet. On August 20, the two armies clashed. Accounts of the battle contradict each other, perhaps because most of the eyewitnesses died; the Battle of Anchialus was the bloodiest day of fighting in centuries. Almost all of Leo Phocas’s officers and tens of thousands of regular soldiers fell. The battleground was unusable for decades afterwards because of the corpses stacked on it; according to Leo the Deacon, piles of bones still cluttered the field nearly eighty years later.

13