The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (69 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

Erik Bloodaxe had earned his nickname from his exploits in battle; Hakon, although just as warlike, was labelled “the Good” because of his faith. Most Scandinavians still worshipped the old gods: Odin with his ravens, the warlike Thor with his deadly hammer, and a whole host of others. But Hakon had spent some time as a child at the court of Athelstan, in England, where he had learned Christianity. Harald Bluetooth had also become a Christian at some point, but the conversions didn’t particularly inconvenience either man; being a nominal Christian simply made it easier to deal with both the English and the merchants on the continent. To “take the sign of the cross,” according to

Egil’s Saga

, was “a common custom then among both merchants and mercenaries who dealt with Christians. Anyone who had taken the sign of the cross could mix freely with both Christians and heathens, while keeping the faith that they pleased.”

16

But when Hakon the Good finally died on the battlefield, fighting against his nephew Harald Greycloak, Christianity came strongly to the fore. With the help of Danish troops provided by his uncle Bluetooth, Harald Greycloak, son of Erik Bloodaxe but himself a convert to the new faith, seized the throne of Norway. He soon proved to be a Christian of a more zealous and driven kind. He could “do nothing to make the men of the land Christians,” says the twelfth-century chronicler Snorri Sturluson, but “broke down temples and destroyed the sacrifice and from that…got many foes.”

17

Unfortunately, Harald Greycloak’s sacking of the old places of worship was followed by hard winters, poor crops, and bad fishing: “There was great want in the land,” chronicler Sturluson writes, “and folk lacked everywhere corn and fish.” An unnatural cold snap caused snow in midsummer. Harald Greycloak grew more and more unpopular with his people; resentment grew against him; and this gave his uncle Bluetooth an opportunity.

18

Harald Bluetooth had not supported his nephew’s claim to the throne of Norway out of the goodness of his heart; he hoped to add Norway to his own Danish kingdom. As Harald Greycloak grew less popular, Bluetooth plotted with one of his noblemen, Hakon of Hladir, to assassinate the Norse king. Around 976, the plot came to fruition. Greycloak was betrayed and murdered; Harald Bluetooth took the eastern Norse lands for his own and, for his trouble, awarded Hakon of Hladir control of the upper Norse coast. He did not allow Hakon to take the title of king, though; and so for a time, the Danish and Norse lands lay under the control of Harald Bluetooth. He kept firm hold on them with the help of his son and warleader Sweyn Forkbeard.

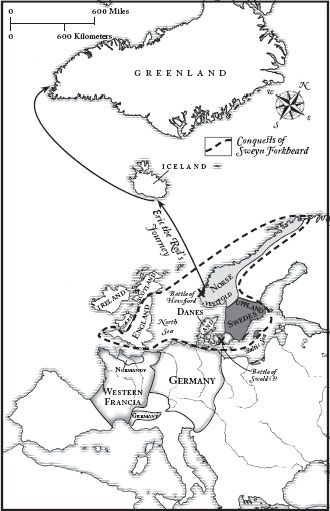

For the next decade, Harald Bluetooth’s soldiers and explorers ranged south and west, pushing the sphere of his power ever outwards. Danish soldiers attacked the borders of Germany, which was now under the rule of Henry the Fowler’s son Otto. More raiding parties went west again to England, where Edgar’s ten-year-old son Ethelred had been crowned as king. And the Norseman Eric the Red sailed northwest, pushing Scandinavian power past the island of Iceland to more distant shores.

Eric the Red, a troublemaker by nature, had been forced to leave Norway and settle in the Icelandic colonies after a feud with another villager that ended in death (Eric’s henchmen, according to the thirteenth-century

Saga of Eirik the Red

, “caused a landslide” to fall on the man’s farm). In 982, he started a brawl with one of his Icelandic neighbors and killed two of the man’s sons. The other colonists forced him to leave Iceland, and Eric the Red set sail, searching for a new place to live.

19

69.2: Spread of Norse Power

After three years of exploring, he settled on a massive island five hundred miles to the west. There were no people on it, which suited his personality, but he had ambitions to found a new colony there. Thanks to the unusually warm temperatures during Eric’s lifetime, the island’s shores were partly free from ice, but it was an inhospitable, bare, sandy place. Eric named it Greenland: as his epic notes, “people would be attracted there if it had a favorable name.” The ruse was successful, to a point. Colonists came, although very slowly, building a tiny outpost of Scandinavian power halfway across the north Atlantic.

20

Back home, old Harald Bluetooth died by the sword. His son Sweyn Forkbeard had hoped that his father would divide his realm and give part of it to Sweyn, but Harald Bluetooth had not fought for his whole life in order to yield his kingdom to his son. As his father’s righthand man, Sweyn had ships of his own. He gathered them and challenged Harald Bluetooth for the throne. In a sea battle fought in 987, Harald Bluetooth turned back his son’s ships. But in the fighting, he was badly wounded. He died just days later, and Sweyn Forkbeard’s followers proclaimed him king.

21

Sweyn inherited the throne of Denmark, the Danish-controlled lands in Norway, and (theoretically) the loyalty of Hakon of Hladir, ruling the upper coastal lands. With an eye to further expansion, he stepped up the raids on England, and the young English king Ethelred found himself unable to stop them. Scorn for the king who was incapable of protecting his people bursts out from William of Malmesbury’s account: “Ethelred occupied (rather than ruled) the kingdom,” he writes. “His life [was] cruel at the outset, pitiable in mid-course, and disgraceful in its ending.”

22

The Danes ravaged Wessex, burned the city of Exeter, pillaged Kent. The death of able-bodied Englishmen in battle and the destruction of crops plunged England into deepening famine and distress. In 991, the East Saxon nobleman Brihtnoth, leading a massive force against the Danish enemy, was killed at Maldon and his army was routed. Ethelred’s advisors suggested that the time had come to pay off the invaders; and, following their lead, Ethelred agreed to hand over ten thousand pounds of silver to the Danes.

23

Sweyn Forkbeard accepted the payment, known as the Danegeld, and withdrew. But Ethelred’s solution turned out to be self-defeating. Sweyn’s original intention had been to conquer the island; the chronicler Snorri Sturluson claims that Sweyn made an oath, at his coronation feast, “that ere three years were gone he would go to England with his army and slay King Ethelred and drive him from his land.” But he now realized England could be far more useful as a source of income. So Sweyn had extended his own deadline; it was better to allow Ethelred to pay his expenses than to try and conquer him. In 994, Sweyn himself returned and fought all the way to London. Once again Ethelred bought him off. But the English king’s ability to raise ransom money from his noblemen was almost tapped out, and no one doubted that the Danes would return.

24

In the meantime, Sweyn used the English cash to fund his conquest of the rest of Norway. Late in 994, Hakon of Hladir died, and control of upper Norway was claimed by a grandson of old Harald Tangle-Hair, Olaf Tryggvason. Sweyn Forkbeard was a formidable enemy, and Olaf’s reign was short. In 1000, his warships clashed with Sweyn’s in the western straits of the Baltic at the Battle of Swold. The Norse ships were sunk, one by one, and King Olaf found himself standing on the deck of his own flagship, the

Long Serpent

, surrounded by the dead. “So many men on the

Serpent

were fallen that the railings were empty of men,” Sturluson says, “and [Sweyn Forkbeard’s] men began to come aboard on all sides.” Olaf leaped overboard and was never seen again. Triumphant, Sweyn Forkbeard claimed all of Norway for himself.

For years, it was rumored that Olaf would return from the depths and free Norway from its Danish overlords. “About King Olaf, there were afterwards many tales,” Sturluson concludes, “but he never again came back to his kingdom in Norway.”

25

Now in control of both Norway and Denmark, Sweyn Forkbeard turned back to the English project.

Ethelred of England, now in his early thirties, had spent his entire reign so far fighting against Danish invasion. In an attempt to get the Normans on his side against the Danes, their distant relations, he had offered them a powerful alliance: he would marry Emma, sister of Duke Richard the Good of Normandy, if the Normans would provide him with soldiers to help fight off the Danes. “For Richard was a valiant prince, and all-powerful,” writes the chronicler Henry of Huntingdon, “while the English king was deeply sensible of his own and his people’s weakness, and was under no small alarm at the calamities which seemed impending.”

26

Ethelred had already been married once and had fathered four sons, so it wasn’t likely that any of Emma’s children would ascend to the English throne. Still, the duke of Normandy liked the idea of an English alliance; it would further prove his independence from the kings of Western Francia. In 1002, Emma travelled to England for the wedding and was crowned queen of England.

But even with Norman reinforcements, Ethelred could not muster a force large enough to turn the Danes away. Nor could he raise enough money to buy them off. He was staring defeat and death in the face. Right after the wedding, he flew into a panic and ordered a drastic step. All Danish settlers in England were to be murdered: man, woman, and child.

The massacre was carried out in a single day. On November 13, 1002, the king’s men spread throughout the island, slaughtering the Danes in every village. In Oxford, Danish families fled to the church of St. Frideswide; the soldiers burned it down with them inside. “All the Danes who had sprung up in this island,” Ethelred later wrote, defending his actions, “sprouting like weeds amongst the wheat, were…destroyed by a most just extermination.”

27

Sweyn Forkbeard had already determined to conquer England. The massacre lent him the justification of revenge. William of Malmesbury insists that Sweyn’s own sister, who had married an Englishman, was killed on November 13. This may or may not be true, but without a doubt, relatives of Sweyn’s own soldiers died in the purge, and anger as well as ambition now fueled the Danish attacks.

28

Sweyn continued to fight a measured, planned war. Over the next ten years, he sent multiple armies to England. The invasions occupied all of Ethelred’s time, killing his soldiers and draining his treasury. The Danes would attack, sack and burn, accept a payment, and then withdraw; each time, Ethelred seems to have hoped that the Danegeld would keep them away for good; each time, they returned.

In 1013, Sweyn Forkbeard himself arrived on the northern coast of England, ready for his final push against the English king. His forces swept southward across the countryside, and the English surrendered, one village at a time. As he approached London, where Ethelred had taken shelter, the Londoners shut their gates. “The inhabitants of the town would not submit,” the

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

tells us, “but held out against them with full battle because King Ethelred was inside.”

29

With the rest of the country in his hands, Sweyn turned aside from London and went to Bath, the city where the first coronation of an English king had taken place. In Bath, he announced himself “King of England,” and demanded that all the English recognize his title.

The city of London, which was the only holdout, had been inspired by Ethelred’s presence. But as soon as Sweyn Forkbeard left for Bath, Ethelred fled to the Isle of Wight, sending his wife Emma and her two sons to Normandy to stay with her brother, the duke Richard the Good. Without their king, the Londoners crumpled. They sent tribute and hostages to Bath, acknowledging the Dane as their ruler.

30

Sweyn Forkbeard now ruled a North Atlantic empire that stretched across the Baltic and the North Sea. He celebrated Christmas in England as its king. A century and a half after the Great Army of the Vikings landed on English shores, the island had finally fallen under Scandinavian rule.