The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (65 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

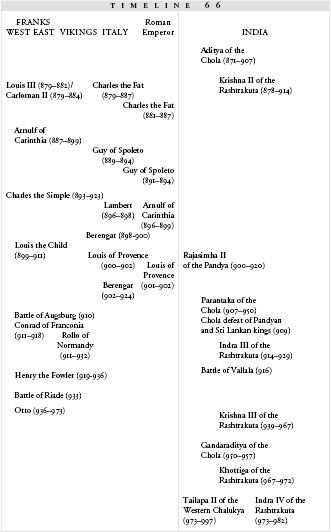

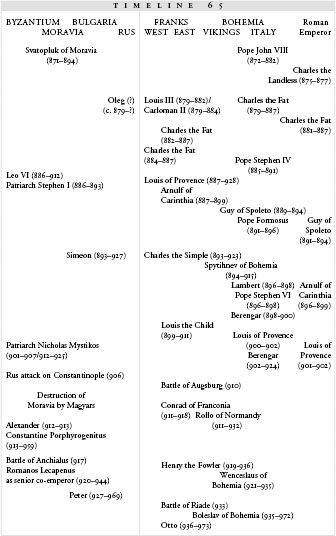

Between 907 and 935, Henry the Fowler transforms Eastern Francia into Germany

W

HILE

C

HARLES THE

S

IMPLE

was solving his Viking problem, Louis the Child was desperately fending off Magyar invasions. As soon as their employer Arnulf of Carinthia had died, the Magyars had romped through Moravia and into Eastern Francia, burning, destroying, killing, and horrifying the Franks with their ferocity: “Nothing pleases them except to fight,” Liudprand of Cremona wrote. “Their mothers cut their boys’ faces with very sharp blades as soon as they come into the world, so that, before they may receive the nourishment of milk, they may learn to endure wounds.”

1

By 907 the Moravian kingdom had disintegrated under their assaults, and the Frankish noblemen had taken on the job of protecting their lands from Magyar destruction.

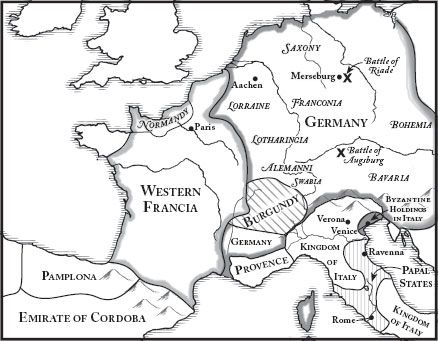

Louis the Child was neither a hardened soldier nor a strong ruler. Crowned at the age of six, he had given over rule to a council of regents and officials and had never fully taken it back; his weak reign had allowed the tribal territories of Francia, the lands that had once belonged to the Germanic barbarian tribes, to regain their character as semi-independent kingdoms, or “duchies.” Although the territories had once been defined by tribal loyalties, those bonds were now in the past. The land of the Saxons had become the Duchy of Saxony, the Bavarians had lent their name to Bavaria, and a handful of other duchies (Lotharingia, Franconia, Swabia) lay around them.

*

Each of these duchies was controlled by a powerful family, and the heads of these families—the “dukes”—were now forced to defend themselves against the plunderers from the east. They raised their own armies, fought their own battles, ruled their own lands, and paid less and less attention to their supposed king.

2

In 910, at the age of eighteen, Louis the Child tried to make one huge push against the Magyars, in a double bid to defeat the invaders and to assert his own power. He assembled the noblemen, their armies, and his own soldiers into a great army at Augsburg, ready to face the Magyar threat.

The Magyars approached more quickly than Louis expected and attacked before dawn, catching many of the soldiers still in their beds. Hours of fighting followed, with heavy casualties on both sides: “the meadow and the fields completely littered with corpses, and river and banks turned red by the blood that mixed in.” Towards evening, the Magyars pretended to retreat; when the Frankish army broke rank and chased after them, the Magyars doubled back around and attacked from behind. The Frankish resistance was broken, the army scattered. Louis’s bid had failed. The defense of the Frankish lands returned to the hands of the dukes. Louis retreated to a monastery and died there, less than a year later.

3

When he died, Charles the Simple claimed, as an obvious truth, that Western Francia and Eastern Francia should be reunited under his rule. But the dukes of Eastern Francia refused, unwilling to give up their own power to a Carolingian king who would insist on his right to control them. Instead, they elected as king one of their own: Conrad, duke of Franconia.

Conrad was supposed to rule as a leader among equals, not as a king with unquestioned royal power, but the other dukes had mistaken their man. Once he had a crown on his head, Conrad began to act like a Carolingian monarch, with all of the accompanying pomp; the crown, Liudprand of Cremona dryly notes, “was not just decorated but

burdened

with most precious gems.” He insisted that the dukes acknowledge his power and follow his bidding. When they refused, he spent the next seven years fighting against them, trying without success to force them into obedience.

4

When Conrad died in 918, the dukes gathered together and decided to try again. This time, they elected the duke of Saxony to be their leader. Henry the Fowler (the nickname came from his love for bird-hunting) was in his early forties, had been duke of Saxony for seven years already, and had a keen appreciation for the independence of the duchies; he too had resented Conrad’s attempts to rule as a monarch. In his first three years as king of Eastern Francia, Henry negotiated a series of oaths between himself and the dukes of Eastern Francia. The oaths of “vassalage” laid out an almost-equal relationship; they acknowledged that both kings and dukes had responsibilities towards each other, and recognized the dukes as “senior partners” in the job of governing, with authority to administer their own laws and lands as they pleased.

5

When the noblemen in Western Francia rebelled against Charles the Simple in 922 (they were unhappy with his decision to give away Normandy), Henry the Fowler took the opportunity to claim a slice of the western kingdom as his own. By 925, five duchies—Franconia, Saxony, Bavaria, Swabia, and Lorraine—made up the core of Henry’s kingdom, and Henry controlled Aachen itself, Charlemagne’s old capital.

6

65.1: Germany

But Henry still made no effort to become a “Carolingian” monarch. In Henry’s hands, Eastern Francia was becoming something new. It was no longer a kingdom of Franks, but a kingdom in which the old Germanic tribal identities were playing a larger and larger role: a Germanic kingdom, a kingdom of Germany.

H

ENRY’S OPEN-HANDED RULE

made it, paradoxically, easier for him to unite the dukes behind him when necessary; they no longer feared that answering a royal command might chip away at their own power. In 933, he summoned the duchies to join him in halting the Magyar advance.

The armies met at the Battle of Riade, near the eastern fortress of Merseburg. Perhaps mindful of Louis the Child’s horrendous defeat twenty-three years earlier, when Henry himself had been in his mid-thirties and fighting with the Saxons, Henry gave his troops very specific directions:

Let no one try to advance beyond his comrades, though he has a faster horse; instead, take the first strike of their arrows on your shields…then rush on them with the fastest charge and with the most vehement attack, in such a way that they cannot fire a second volley of arrows on you before they feel the cuts of your weapons upon them.

7

Liudprand of Cremona explains, “The Saxons, mindful of this most salutary warning, charged with an orderly, even line, and there was no one who outran the slower with a faster horse; and they took on their shields the harmless strikes of the [Magyars’] arrows…. [O]nly then did they surmount the enemy with a vigorous charge.”

8

The Magyar advance had been broken; after the Battle of Riade, they retreated back to the east, leaving the German borders in a temporary peace.

As part of his strategy to keep them permanently away, Henry planned to turn the little dukedom on his eastern flank into a vassal state that would act as a buffer between Germany and another Magyar advance. The dukedom was called Bohemia, and like the duchies of Germany it had once been a Germanic tribal territory. When the Magyars had begun to make raids into Moravia, the Moravian nobleman Spytihnev—a Christian whose father had been baptized in Moravia by the missionary Methodius—moved his family to the west, away from the Magyar threat. With the help of Arnulf of Carinthia’s Eastern Frankish soldiers, he had established himself as ruler of the peoples there: the first duke of Bohemia.

9

The new duke of Bohemia was a young man named Wenceslaus, who was a Christian and enthusiastic about an alliance with the powerful German king. Wenceslaus was the grandson of Spytihnev, the first duke; he had inherited his title when he was only fourteen, and his regents had been his Christian grandmother Ludmila, Spytihnev’s widow, and his mother, Drahomira, a young woman who clung to the ancient religions of her Slavic ancestors and refused to be baptized.

Ludmila, who was a forceful matriarch, had taken over the education of the young Wenceslaus, instructing him in Christianity, and she now intended to teach him how to rule as a Christian king. But Drahomira sent two of her palace guards to strangle her mother-in-law and, with Ludmila dead, took over the sole task of regent.

10

Drahomira then began efforts to convert her son back to the ancient ways. But Wenceslaus refused to give up his Christianity, and as soon as he turned eighteen, in 925, he exiled Drahomira and took power in his own name. When Henry the Fowler approached him for an alliance, Wenceslaus agreed.

This was not a universally popular decision. Some of the Bohemian officials at his court thought that Henry was dangerous, that Bohemia’s independence was threatened, and that the Christian religion—which had originally come to them as a tool of domination—only made Bohemia more vulnerable to conquest. Led by Wenceslaus’s younger brother Boleslav, this faction insisted that Wenceslaus break the alliance and give up Christianity as well, all in the name of a strong and autonomous Bohemia.

But Wenceslaus refused. In 935, he came to church in the predawn dark for an early mass; Boleslav and the dissident officials met him at the church’s door and stabbed him to death.

Boleslav then declared himself prince of Bohemia, an act that explicitly rejected Henry’s attempt to make Bohemia into yet another German dukedom. But despite the political nature of the assassination, Wenceslaus was hailed by the Christians in Bohemia as a martyr for Christ. Stories blossomed around him. The fourteenth-century emperor Charles IV made a personal collection of these tales; it is from his manuscript that we hear the story of Wenceslaus walking in the snow with one of his soldiers, in a storm so great that the soldier is afraid they will freeze:

Wenceslaus said to him, “Place your feet in the prints left by mine.” The soldier did so, and his feet became so warm that he no longer felt the cold in the least. But stains of blood could clearly be seen in the prints the glorious martyr left.

11

(This last detail did not make it into the Christmas carol.)

Henry I did not take revenge for his ally’s death, because he had grown ill. In 936, the year after Wenceslaus’s murder, he died. In a decisive break from Frankish tradition, he excluded all but one of his sons from the inheritance, and left the German kingdom whole to his son Otto.

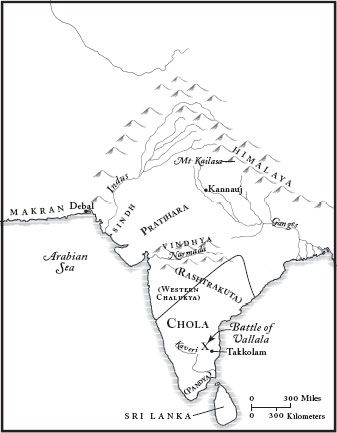

Between 907 and 997, the Chola kingdom rises and falls, the Pandya kingdom falls and rises, the Rashtrakuta kingdom falls, the Western Chalukya kingdom rises

T

HE

R

ASHTRAKUTA KING

, situated uneasily between Pratihara ambitions in the north and Chola expansion in the south, realized that his days were numbered. The Pratihara had already reached its height and was fading, drained by the effort of fighting wars on its southern border and holding off the Arabs in the north. But the southern Chola realm was still in its ascendancy, its greatest years yet to come. Aditya, the ambitious Chola king who had defeated the Pallava, had just died after a thirty-six-year reign; his son Parantaka, inheriting his crown, would inevitably push north against the Rashtrakuta.

But first, Parantaka embarked on the conquest of the remaining Pandyan resistance in the south. The Pandyan king, Rajasimha II, knew that he could not resist the Chola armies all alone. Finding an ally was no easy task, though; after nearly four decades of Chola expansion, few kings were willing to defy the new Chola king.

Instead, Rajasimha II was forced to send a message across the southern strait, to the island of Sri Lanka.

1

The Sri Lankan king agreed to the alliance. In 909, Sri Lankan armies sailed across the water and joined with the Pandyan forces. Together, they fought against the Chola threat—and were completely defeated. Parantaka’s commemorative inscription boasts that the Chola army not only crushed the two kings but also slew “an immense army dispatched by the lord of Lanka, which teemed with brave soldiers and was interspersed with troops of elephants and horses.”

2

Rajasimha II of Pandya survived the battle but fled with the Sri Lankan king back to the southern island, where he remained in hiding. He took with him his crown and his royal regalia, and for the next decade he planned and schemed in exile to get his throne back.

Meanwhile, the Chola steamroller made a turn to the north and met the Rashtrakuta armies. Krishna II, whose rule had been even more disastrous than that of his long-lived father, had just died in 914, and his grandson Indra III became king in his place. Right at the beginning of his reign, the inexperienced king was forced to defend himself against the Chola threat.

Sometime around 916, the two armies met at the Battle of Vallala. Once again, the Cholas triumphed.

The Chola king Parantaka had now defeated three kings in succession: the rulers of Sri Lanka, Pandya, and Rashtrakuta. His dominance seemed inevitable. Down in Sri Lanka, the exiled Pandyan king gave up all hope of ever recovering his throne. He left his crown and regalia in Sri Lanka and went home, back to his mother’s ancestral lands on the southwestern coast of India, well away from the places where he had once held power. The Pandyan kingdom had disappeared, swallowed by the Chola aggression.

3

The Rashtrakuta still clung to life, though, and after his defeat at the Battle of Vallala, Indra III of the Rashtrakuta tried to regain his power by turning north against the unstable Pratihara. He managed to fight his way all the way to the crown jewel of the Pratihara kingdom, the city of Kannauj itself, and conquer it. For a brief moment, the Chola and Rashtrakuta kingdoms dominated the subcontinent between them, while the Pratihara dwindled away almost to nonexistence.

But Indra III died prematurely in 929, and his successors fought over the throne. Four kings followed in quick succession, as the Rashtrakuta kingdom turned inwards. Parantaka of the Chola, relieved from the immediate threat of Rashtrakuta invasion, was able to firm up his hold on the south. Around 943, he sent an expedition down into Sri Lanka on a secret mission to find and bring back the regalia that the Pandyan king had left there, more than twenty years earlier. The effort failed, but even without the regalia, the Chola had now become the strongest kingdom in all of India.

4

Parantaka’s four decades on the southern Chola throne had been glorious, but it all fell down in a hurry. The Rashtrakuta chaos came to an end when Krishna III, great-nephew of Indra III, seized the throne. He would prove to be a talented administrator, a fierce warrior—and the last great Rashtrakuta king.

5

Krishna III marshalled his forces to attack the dominant Chola, and in 949 the two kings met in battle at the city of Takkolam. Their forces were evenly matched, and a bow drawn at a venture decided the victory; a chance arrow killed Parantaka’s son, the crown prince Rajaditya Chola. When he fell, the wing of the army under his command scattered, and the chain reaction infected the whole Chola army. Parantaka was forced to retreat and to hand over northern territory—and, as the lack of inscriptions over the next decades indicates, was probably forced to pay homage to Krishna III as a subordinate ruler.

6

66.1: The Height of the Chola

It was a sudden and shattering reversal. Grief-struck, his power fractured, Parantaka of the Chola died in 950. He had made his younger son Gandaraditya crown prince, after the death of his eldest and favorite child. And Gandaraditya, who was a careful and pious man, dealt a death blow to the empire.

The Chola, after all, had laid the foundation of their empire with their swords. They claimed power by right of conquest. The great warrior-kings of the previous century had forced cities and warlords to swear allegiance to the Chola throne, and had then boasted of the extent of their kingdom based on the vast amount of land under their sway. The development of any kind of infrastructure had lagged far, far behind. A weak double web—the threat of the king’s armies, and the building of Hindu temples in the king’s name—held the Chola expanse together.

Until Gandaraditya’s coronation, the building of temples had been a valuable tool of Chola dominance. The kings who ruled after Vijayalaya, the founder of the empire, were Shaivite: like the northern empire-builder Harsha and his sister long before, they were devotees of the god Shiva and his divine consort. Later inscriptions tell us that the great Chola expander Aditya, most certainly a man of war, had built temples for Shiva to inhabit “all along the Kaveri River,” a sacred watercourse. Like the Pandyan regalia, the temples were a symbol of power. The Chola kings did more than simply fight; they had invited the god to come and live in their empire, and the invitation was itself a boast of their dominance.

7

But the temple-building, although important, had been a secondary tool of Chola dominance—until Gandaraditya. He and his queen, Sembiyan Mahadevi, were particularly devout followers of Shiva. Together they began to build new temples and repair old ones, all through the Chola realm. This stamped their names across the countryside; at the same time, though, Gandaraditya let the exercise of political power slide through his fingers. Piety was more to his taste than warfare. So far as we know, Gandaraditya fought no major battles. Instead he made his younger brother Arinjaya his heir and co-regent and handed the day-to-day administration over to him.

Arinjaya was not a talented ruler, and the Chola kingdom began to fade. Before long, the Chola authority was so weakened that a relative of the Pandyan king came out of obscurity and claimed the old Pandyan lands for himself. By 957, both brothers were dead, and the Chola kingdom had dwindled back down to a tiny state. Its northern territory was occupied by the Rashtrakuta, under the rule of Krishna III; in the south, the Pandyan pretender had reclaimed his land.

8

The sudden Chola decline might have allowed the Rashtrakuta king to swing the balance of power back in his direction, but the Rashtrakuta empire too was troubled by rot at the top. In 967, Krishna III died. He had ruled for nearly thirty years and had managed to save the Rashtrakuta empire from disintegration. But now it too began to fall apart. Krishna III’s successor, the weak Khottiga, faced a welter of revolt around the edges of his realm; and in 972, after less than five years on the throne, he was killed in a minor battle at the border.

Now revolt moved to the center of the empire. A Western Chalukya warleader named Tailapa had been waiting, watching the empire disintegrate from the top down. He declared independence and crowned himself as Tailapa II, king of the Western Chalukya—the first Western Chalukya leader in two hundred years to claim sovereignty.

The unfortunate royal relative who held power in the Rashtrakuta palace, a young man named Indra IV, was forced to take up arms against this rebellion. But in 975, Tailapa inflicted such a horrendous defeat on the Rashtrakuta army that all hope of Rashtrakuta recovery was gone. Indra IV’s chief ally, his uncle Marasimha, was so humiliated that he retreated from the war, set the struggle for power aside, and starved himself to death. The ritual suicide, called

sallekhana

, was an honorable way out: it earned merit for the one courageous enough to commit to it, and offered the possibility of a permanent end, the cessation of the cycle of birth and rebirth.

9

Centuries of war had done nothing but turn the wheel of fortune, bringing one empire and then another to the top.

Sallekhana

might not stop the wheel, but at least Marasimha could make a stab at getting off.

After another seven years of struggle, Indra IV too gave up. He followed his uncle in

sallekhana

and died of starvation in 982: the last Rashtrakuta king. Tailapa II of the Western Chalukya seized his territory, in one stroke becoming ruler of the center of India and soon, with aggressive campaigning, extending his empire all the way up to the Narmada. Kingdoms fell; kingdoms rose; the wheel turned on.