The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (70 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

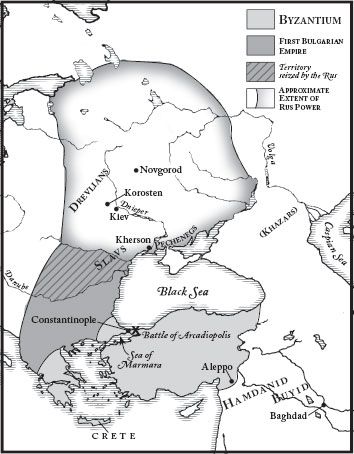

Between 944 and 988, the Rus fight against the enemies of Constantinople, and then attack Constantinople, and finally convert to Christianity

T

HE SENIOR EMPEROR

Romanos Lecapenus was balancing Constantinople carefully on a very narrow spit of political safe ground. The ambitious emirs of the former Abbasid caliphate were continually driven away from his borders by yearly campaigns, costly in men and money but crucial for Byzantium’s survival. On the other side of the city, the triangle of western powers—the Rus, the Bulgarians, and the constantly invading Magyars from the north—were kept at bay through a combination of negotiation, threat, and tribute payment. Assuring Constantinople’s safety was an exhausting and exacting job, but Romanos had managed it for over twenty years.

He was now seventy-four years old and ruled along with four co-emperors. Constantine Porphyrogenitus, son of Leo the Wise, still lived in Romanos’s shadow; he was married to Romanos’s daughter Elena, and was forced to share the title of emperor not only with Romanos but also with Romanos’s two sons and his oldest grandson, all of whom had been crowned as co-emperors.

1

Romanos had arranged the coronations to ensure the succession for his own family. But in 944 his two sons, Stephen and Constantine Lecapenus, grew weary of waiting. With the help of their own personal bodyguards, they pulled their elderly father from his throne and put him on a ship headed for a monastery on a desolate island in the Sea of Marmara.

This turned out to be only the first act in the drama. Apparently all four co-emperors were in on this plot, but Constantine Porphyrogenitus—now thirty-nine, diffident and unassertive by nature—had allowed the two younger men to carry it out. Stephen and Constantine Lecapenus assumed that this gave them the authority of senior emperors, and Constantine Porphyrogenitus wasn’t inclined to argue with them.

But their sister, Constantine’s wife Elena Lecapenus, did not intend to share imperial power with her brothers. She had been married to Constantine Porphyrogenitus for twenty-six years, ever since she was nine, and she had grown to adulthood along with her amiable, unambitious husband. She knew he would never grasp the crown for himself.

She arranged for her brothers to come to dinner, and convinced her husband to authorize their arrest during the meal. The royal guard seized them as they sat down to eat. Both men, along with Romanos’s grandson (the other co-emperor), were put on ships and sent to distant monasteries, suffering the same fate as their father. Constantine Porphyrogenitus was, after nearly forty years of eclipse, the sole emperor of Constantinople.

2

Romanos would die at his monastery of peaceful old age, three years later. He had failed to guarantee the crown for his sons, but his dynasty survived; the heir to the throne, Constantine’s seven-year-old son, was Romanos’s grandson.

C

ONSTANTINE

P

ORPHYROGENITUS

began his reign as senior emperor by negotiating a treaty with the Rus. For over two centuries, the empire of By zantium had turned its battle face east: the armies of Islam had been the single most enduring, most persistent threat to Constantinople. But the Rus, barely civilized in the eyes of Byzantines, were just as anxious as the Arabs to take their turn at besieging the great city by the sea.

Less than thirty years earlier, the Arab geographer Ibn Fadlan had travelled up the Volga, through the lands of the Khazars into the domain of the Rus. His accounts raise the curtain on a people still half-wild: always armed, tattooed from neck to fingertip, living in temporary wooden shelters, copulating in public, and sacrificing to strange bloody gods. “They are the dirtiest creatures of God,” Ibn Fadlan wrote, hardly able to believe the disgustingness of their habits:

A slave girl brings each morning early a large vessel with water, and gives the vessel to her master, and he washes his hands and face and hair. Then he blows his nose and spits into the bucket. The girl takes the same vessel to the one who is nearest, and he does just as his neighbor had done. She carries the vessel from one to another, until each of them has blown his nose, spat into, and washed his face and hair in the vessel.

3

Bands of Rus merchants travelled long distances, buying and selling but never bothering to build. To Ibn Fadlan’s eye, they were completely transient, leaving nothing behind them: not even burial grounds, since they preferred to burn their dead.

4

By 945, the Rus had grown some visible roots. They had a capital, a prince, and at least the semblance of a central government: Igor, prince of Kiev, had enough power to swear out a treaty on behalf of his people with Constantine Porphyrogenitus. The treaty bound both parties, once again, to observe the terms laid out in the 911 peace: Rus merchants could enter Constantinople, but they had to be unarmed and in groups of no more than fifty men; if they went back to Kiev peacefully, they would get a month of free food; and if Constantine Porphyrogenitus needed soldiers to keep the Bulgarians or Arabs at bay, the Rus would serve in the Byzantine army as paid mercenaries.

5

The treaty catches the Rus in mid-transformation, partway through the complicated (and by now familiar) morph from tribal collection into kingdom. Igor’s role in negotiating it was kinglike, and the terms of the treaty were Byzantine: “If a criminal takes refuge in Greece, the Rus shall make complaint to the Christian Empire, and such criminal shall be arrested and returned to Rus regardless of his protests,” reads one article, laying out the sovereign right of each state to execute justice on its own people, “and the Rus shall perform the same service for the Greeks.” But the Rus who put their names to it, underneath their princes, were fifty warleaders with a mixture of Viking and Slavic names, each boasting the limited authority of a tribal chief.

6

Right after signing the treaty, Igor met the death of a tribal chief. The Rus had conquered the Slavic tribes on the western side of their lands, the Drevlians, fifty years earlier; but the Drevlians had continued to resist their rulers. On his way back from signing the treaty, Igor made a detour through Drevlian territory to collect overdue tribute. “He was captured by them,” writes Leo the Deacon, “tied to tree trunks, and torn in two.”

7

His wife Olga took over as regent for their son Svyatoslav. Her first act was to burn the Drevlian city of Korosten to the ground and slaughter hundreds of Drevlians in revolting ways, burning and transfixing and burying them alive. But Olga too was changing. Once her warrior-queen revenge was finished, she picked up the task of turning the Rus into a state; she divided her realm into administrative districts,

pogosts

, each one responsible for a set tax payment. The Drevlians became their own

pogost

, with regular payments due to the government at Kiev.

8

In 957, Olga made a state visit to Constantinople, where Constantine received her as a fellow sovereign. The floors of the imperial palace were strewn with roses, ivy, myrtle, and rosemary; the walls and ceilings were hung with silken drapes; a choir from the Hagia Sophia sang as she was ushered into the emperor’s presence; and mechanical toy lions in the throne room roared in her honor. She was banqueted and entertained for over a week. At the end of her visit, she agreed to be baptized. Constantine’s wife Elena stood as her godmother, and Olga of the Kievan Rus was welcomed into the spiritual family of Byzantium.

9

In less than half a century, the Rus had progressed from their wooden shelters by the Volga to the royal reception halls of Constantinople. It was an extraordinarily fast metamorphosis—and it proved to be partly temporary.

In 963, Igor’s son Svyatoslav took power in his own name, at the age of twenty-one. His mother Olga retired from public life and spent her time trying to talk her fellow Rus into accepting Christianity. Her conversion had not brought the entire country within the fold, and Svyatoslav was a throwback. He was an aggressive, war-minded man who rejected his mother’s faith: “My retinue would laugh at me,” he told Olga, when she suggested that he consider baptism.

10

Instead he “followed heathen usages” and generally behaved like a tribal chief from earlier times:

When Prince Svyatoslav had grown up and matured, he began to collect a numerous and valiant army. Stepping light as a leopard, he undertook many campaigns. Upon his expeditions he carried with him neither wagons nor kettles, and boiled no meat, but cut off small strips of horseflesh, game, or beef, and ate it after roasting it on the coals. Nor did he have a tent, but he spread out a horse-blanket under him, and set his saddle under his head; and all his retinue did likewise. He set messengers to the other lands announcing his intention to attack them.

11

He spent the first years of his solo rule fighting against the Khazars, the Slavic tribes, and the Turkish nomads called Pechenegs on his east, as Olga’s dream of a Christian people receded.

Meanwhile, in Constantinople, Constantine Porphyrogenitus had died in his mid-fifties, after a reign of indifference to affairs of state.

12

He was succeeded, briefly, by his twenty-one-year-old son, Romanos II, grandson of the usurper Romanos Lecapenus. Like his father, Romanos II was amiable and pleasant and easily manipulated. “He was distracted by youthful indulgences,” Leo the Deacon explains, “and introduced into the palace people who encouraged him in this behavior…. [T]hey destroyed the young man’s noble character by exposing him to luxury and licentious pleasures, and whetting his appetite for unusual passions.” The “people” in question probably refers to his wife Theophano, the beautiful daughter of an innkeeper who had caught his eye when he was eighteen.

13

For the four years of Romanos II’s reign, Theophano and the general Nikephoros Phocas (a career officer who had sworn an oath of chastity after his first wife’s death, and now channelled his energies into conquest) ran the empire. It was a good four years for Byzantium. With his nephew John Tzimiskes at his side as second-in-command, Nikephoros Phocas first led the Byzantine navy in recapturing Crete, and then led the Byzantine army in the conquest of Aleppo, retaking territory that had been lost to the Arabs for decades.

14

In March of 963, the same year that Svyatoslav took control of the Rus, young Romanos II died of a fever. He left his two sons, Basil II (five) and Constantine VIII (three), as co-emperors, with the empress Theophano as regent.

70.1: The Rus and Byzantium

Theophano was still in her twenties; she was not enormously popular (she was suspected by Leo the Deacon, among others, of poisoning her husband with hemlock), and she was afraid for herself and her babies. The general Nikephoros Phocas was on his way back to Constantinople after fighting at the eastern front, and Theophano sent messengers to him, making private offers of alliance and support.

15

It isn’t clear exactly what these offers promised him; Nikephoros Phocas was more than thirty years her senior and had sworn that awkward oath of chastity. But the empress’s letters inspired Nikephoros Phocas to claim the crown. His army proclaimed him emperor in July, while still on the march, and he arrived at Constantinople in August. The patriarch agreed to coronate him in the Hagia Sophia in exchange for Nikephoros Phocas’s promise that he would never harm either of his toddler co-emperors, and on August 16 he became Nikephoros II, emperor of Byzantium.

16

In a matter of weeks, he had also married Theophano, which kept her on as empress and made him the stepfather of the heirs to the throne. But although contemporary historians claim that he was bewitched by her beauty, the marriage was likely a business arrangement. Nikephoros Phocas may well have kept his vow of chastity. Certainly he spent more time on the battlefield, over the next few years, than in the bedroom; he returned to the eastern front and went on fighting the Arabs, while Theophano began a hot and heavy affair with his nephew and chief lieutenant John Tzimiskes, a dashing officer in his late thirties.

Nikephoros Phocas was a lifelong soldier, and now that he was emperor he saw himself not as Defender of the Faith or Chief Administrator of the Empire, but as Supreme Commander. He was a man who could not bear to simply maintain his borders; he was compelled to expand them. In 968, he hired Svyatoslav of Kiev and fifty thousand Rus mercenaries to fight for him and declared war on Bulgaria.

Svyatoslav had just finished reducing the Khazar empire to rubble, and Bulgaria was the next and nearest big target. Like Nikephoros Phocas, the leader of the Rus was a man who had to fight in order to rule. He marched down to the Danube and launched a shattering attack on the Bulgarians—so shattering that he was able to seize the entire north of the country for himself. Peter I of Bulgaria had a stroke and died, leaving his son Boris II in charge of the remains of the country.