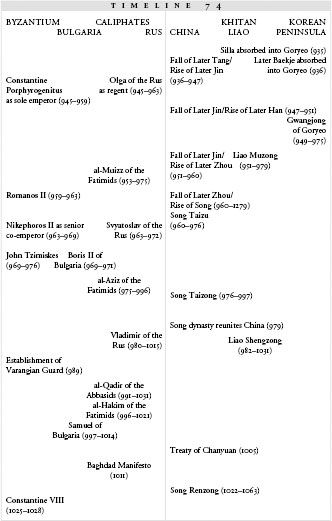

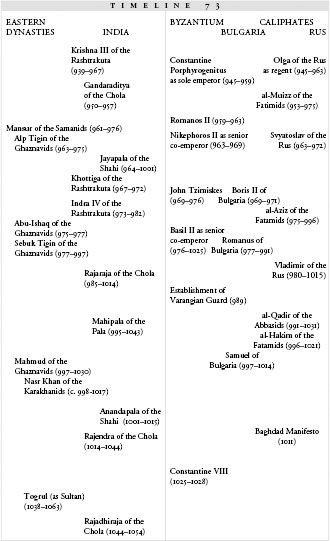

The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (74 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

While the east boiled, Basil led the Byzantine army in a final enormous assault on the Bulgarian border. The two forces met near Kleidion, just north of the Aegean Sea in the old Macedonian lands, on July 29, 1014.

Basil’s break from the war, his refusal to take revenge on the Fatimid regime, had allowed him to rebuild his army into shattering strength. The Bulgarians were laid waste. A contemporary historian claims that fifteen thousand Bulgarian troops were taken captive and arrayed before the victorious Basil.

Basil had absolutely no tolerance for treachery—even treachery carried out in the open by nationalistic freedom-fighters. He ordered ninety-nine out of every hundred captives blinded. The hundredth man was left with only one eye so that he could lead his comrades back to Samuel, who had remained back in the capital city of Ohrid. At the sight of his mutilated troops, Samuel—now an old man, veteran of nearly forty years of war—had a heart attack and died.

12

Without their chief, the Bulgarian resistance faltered. Over the next four years, Bulgarian nobles began to surrender to Basil II, one at a time. By 1018, Bulgaria was again enfolded into Byzantium—this time, all the way to the Danube river.

Meanwhile, al-Hakim of the Fatimids had quietly gone mad. In 1016, he declared himself divine and ordered his name inserted into Friday prayers in place of Allah’s. At this his Muslim subjects joined the Christians and Jews in revolt. Al-Hakim ordered vicious reprisals, but in 1021, with his realm in total chaos, he rode off into the desert alone and disappeared from view. He was thirty-six years old; his successor, his young son, was guided by al-Hakim’s sister, and the Fatimid realm slipped further into disarray.

13

Basil made no attempt to take control of the east. He was an old man by the time al-Hakim disappeared; his life-long war against the Bulgarians had earned him the nickname “Basil the Bulgar-Slayer.” He died in 1025, at the age of seventy-two, and his crown passed on to his younger brother Constantine.

Constantine was now seventy years old and totally incapable of coping with either revolt at home or trouble abroad. Basil, who had spent his entire life stamping out rebellion, had never taken the time to marry; he left behind him an empire built on blood, but no heir.

Between 979 and 1033, the Song emperors fight to prove that divine favor is theirs

T

HREE EMPIRES

had spread themselves across the fractured east: the Song, drawing together the bits and pieces of China; the northern Khitan, transforming themselves from nomads into the Chinese-style kingdom of the Liao; and the single realm of Goryeo. All three had united their lands by force, and the impulse to conquest did not stop just because the worst of the divisions were overcome.

Song Taizong, now in his third year of rule, had done what his brother could not: he had conquered the last holdout state in the old Chinese territory, the Northern Han. Rather than halting, he decided to go on and attack the Liao borders.

Unfortunately, his army was massively beaten just west of Beijing, in a defeat so shattering that it put Song Taizong’s crown in jeopardy. He was already under a cloud of suspicion—more than a few army officers had muttered that his brother’s death was too convenient to be anything but poison, and others objected that Song Taizong had usurped the throne of the dead man’s son, Taizong’s own nephew—but his victories against the Northern Han had temporarily silenced his critics.

1

Now, in defeat, the complaints became audible again. The Song emperors had aligned themselves with the great Chinese emperors of the past, claiming the Mandate of Heaven to bring the divided country back to its former unity. The Mandate of Heaven always had a sting in its gilded tail, though; the Mandate was conditional, held by the ruler only as long as he could prove himself worthy, and it made the removal of unworthy rulers a positive moral duty.

Even more tricky was the

proof

that an emperor held the Mandate. The Mandate descended from the divine realm upon those who were morally upright, and gave the emperor victory against his enemies. So in practice, the strongest proof of the Mandate was success in battle. The victorious emperor could claim, by definition, to be morally worthy, no matter what his private life looked like; the defeated emperor could protest about his upright nature all he liked, but the Mandate had obviously been removed.

2

Song Taizong’s defeat at the border—he was so badly injured in the fighting that his men had to toss him into a donkey cart to get him away from the front line—tarnished the shine of the Mandate. He had listened to army gossip; he knew that his officers might lead a revolt against him at any time, and that his brother’s two sons could be installed on the imperial throne in his place. Back in his capital city of Kaifeng, he called the older of the young princes into his presence. By the time the audience was over, the boy had been made perfectly aware that his uncle intended to kill him. He forestalled the assassination by going to his room and cutting his own throat.

In the next few years, the younger nephew and Taizong’s own brother also died suddenly, and Taizong himself refused to name an heir; his crown was too unsteady. Instead he tried to redeem himself by once again attacking the Liao—against the advice of at least two high-ranking generals who told him that the Song were not strong enough to wipe the northern enemy out.

3

At first, this second campaign met with greater success. In 986, three separate divisions of Song soldiers marched across the Liao border, each headed for a different pass through the mountains. The Liao king, the teenaged Liao Shengzong, and his regent, the empress dowager Xiao, were taken by surprise. Bad intelligence led Liao Shengzong to believe that the Song would also attack by water, so he divided his army and sent half of it to the coast. The Song armies pushed quickly forward against the weakened Liao forces, taking cities in the west as they moved into Liao land. “The Liao,” writes a contemporary chronicler, “was in very, very grave danger.”

4

But the empress dowager Xiao, a formidable old lady with a good head for war, was not ready to retreat. Under her direction, the Liao generals retreated from the Song forces, and then surrounded and attacked them from behind. All three Song armies were defeated; the Liao forced them to surrender and then took their weapons and food as booty.

5

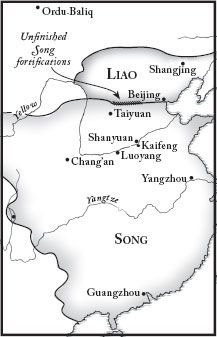

74.1: The Song and Liao

Song Taizong held onto his throne, after this second embarrassing defeat, only because he had killed off all of his possible rivals. But he was forced to give up any thought of recapturing the north of China.

Instead, he turned his attentions back to the rule of his own realm—a place where he expected, daily, to be assassinated or betrayed. His fear of usurpation made him unusually suspicious of any official with royal, or even noble, blood; he also systematically pushed military officers into lower and lower posts with less and less authority. He preferred to rely on bureaucrats of undistinguished families who had passed the civil service exams with flying colors. Belonging to an old noble clan no longer opened a path into government service. The wars of the previous century had already fractured the great families, and Song Taizong’s reliance on the examination system to appoint and promote his officials made noble ancestry even less important.

6

His suspicious nature played midwife to a newly emerging Chinese class: professional bureaucrats who entered political office after years of studying to the test. The old scholar-officials had pursued learning for its own sake; these new officials were more concerned with figuring out what answers the emperor wanted to hear. They became government officials because they had mastered a certain amount of knowledge and were able to parrot it back on the test to the emperor’s satisfaction. They were well educated within very specific parameters, and they were loyal to the emperor. When each candidate passed, the emperor met with him personally, hoping to dazzle the new recruit with imperial favor and persuade him into personal loyalty. The bureaucrats were generally dazzled. They had, after all, no other kind of power—no military accomplishment, wealth, or old family name. They were able, quick-minded, and completely dependent on the emperor.

And they quickly filled the ranks of Chinese government. Song Taizong’s willingness to appoint and promote anyone who had passed the exam attracted hordes of seekers to the capital. In 977, five thousand men had sat for the civil service exams; in 992, over seventeen thousand tried their hand at it.

7

Song Taizong finally named an heir to his crown in 997, when he felt his final illness taking over. His eldest son had gone mad, and his second had died. His choice fell on his third son, who shortly after his father’s death was crowned as Song Zhenzong. The new emperor was twenty-nine; he had always been Song Taizong’s favorite child, possibly because he was passive, agreeable, uninterested in fighting, and unlikely to grab his father’s throne prematurely.

8

Unfortunately, these were not useful qualities for an emperor who had inherited a kingdom with an enormous and growing bureaucracy and a hostile, ambitious northern neighbor. Yearly raids from the Liao were causing increasing angst in the northern reaches of the Song empire, and Song Zhenzong’s first big project was to build a series of canals and dikes along the Song-Liao border, dotted with well-garrisoned fortresses, to keep the Liao troops out. It promised to be a formidable barrier, and as it neared completion, the Liao—still ruled by Liao Shengzong, no longer a teenager and hardened by twenty years of rule—launched a last major attack against their southern neighbor, bursting through the unfinished fortifications and sweeping southwards.

9

Song Zhenzong folded. The raids of the previous years had seen Song soldiers killed, Song villages burned, Song farmlands destroyed; and although he had sent armies north again and again, the Liao threat had never wavered. The empires were deadlocked.

In 1005, Song Zhenzong agreed to peace terms that were unequivocally humiliating to the Song. The Liao would give up their attempts to seize Song land; both kings would respect the border and build no more fortifications along it; the Song emperor would address the Liao ruler properly, as an emperor in his own right; and the Song would hand over two hundred thousand bolts of silk and a massive payment in silver—equivalent to about one and a half tons—to the Liao every single year. Song Zhenzong told his people that the payment was a “gift of an economic nature” Liao Shengzong told

his

people that the payment was tribute from a subject people.

10

The Liao wording was probably closer to the truth. The Song were not subjects, but when Song Zhenzong signed the Treaty of Chanyuan, he brought an end to the first era of the empire’s existence. Conquest had brought the Song into existence; now the time of conquest was ending. Zhenzong had turned the empire’s gaze from the outside to the inside, giving up the uncertain glories of conquest in favor of predictable and peaceful co-existence.

For the next fifteen years, Song Zhenzong devoted himself to domestic matters. His first order of business was to make sure that his people knew the Mandate of Heaven had not deserted him. He had not exactly been defeated by the Liao, but he certainly hadn’t triumphed over them, and the jury was still out on whether or not the Mandate was firmly his.

In 1008, the emperor made a startling discovery: a sacred text, buried in the palace grounds, explaining that the Song dynasty reigned with heaven’s favor. Then Song Zhenzong had a supernatural vision, which he described in great detail to his people: the mythical and sacred first emperor of China had appeared and explained that he, the Yellow Emperor, had been reincarnated as Zhenzong’s ancestor. Not only did Zhenzong have the Mandate of Heaven, but his clan was literally (more or less) descended from China’s greatest ruler.

11

It is impossible to know how much of this dog-and-pony show the people of Song China actually believed. But despite his weaknesses as a ruler, Zhenzong apparently had a flair for stage management; he put on a whole series of sacrificial pilgrimages and built memorial structures to commemorate each discovery and vision. Even more to the point, the Song people were growing wealthier and more comfortable in the absence of war. The population doubled in just a few decades, in part because Zhenzong had introduced a new kind of rice into his country: he had bought thousands of bushels of a quick-maturing, drought-resistant seed from rice-growers in the far south and imported them into the north for use by the Song farmers. The new rice grew so quickly that two crops per year could be planted and harvested, and its tolerance for dry land meant that fields farther north and higher up could now yield a crop.

12

Song Zhenzong died in 1022, leaving his empress as regent for his young son. The new emperor, Song Renzong, embarked on his own solo reign when his mother died, eleven years later. He was twenty-four, and over the next thirty years he would preside over a richer and richer country.

Without major wars to fight, tax money went not to the army but to roads, buildings, schools, and books. Books were in higher demand than ever; like his grandfather, Song Renzong relied on the results of the civil examinations when he chose his officials, which meant that young men all over the empire were buying the standard texts and studying up, hoping to ascend the first rank of the professional ladder. The technique of printing books with carved wooden blocks, rather than writing them by hand, made it possible to produce multiple copies of the most popular books and to sell them for prices that wouldn’t break a student budget. Song Renzong himself was a collector; a catalogue of his personal library lists eighty thousand volumes.

13

Woodblock printing proved useful in another way as well. Up until this point, the Chinese economy had been fed with heavy coins, which were awkward to carry even in small amounts, let alone large stacks. A system for dealing with these massive piles of metal had evolved: merchants would leave their coins in special, privately run “deposit houses,” receive stamped receipts, and then use the receipts to buy and sell. Song Renzong, anxious to encourage trade, helped this sensible practice along: sometime early in his reign, a royal office was established in the city of Chengdu to print these receipts in set amounts. The woodblock receipts, circulated through the markets of Song China, served as the world’s first paper money.

14

Giving up war had been an act of surrender, but the temporary peace that followed the Treaty of Chanyuan allowed Song China to grow rich. And prosperous and well-fed people, it turned out, were not inclined to be skeptical of the Mandate—even in defeat.