The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (33 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

Swords had played little part in the defeat.

Hoping to avoid a repeat attack, the tribes of southern Arabia asked Khosru for aid. In 575, he came south with both foot-soldiers and a fleet of ships, into the land Abraha had hoped to conquer.

The Persian intervention halted Abraha’s attempts to organize a second invasion. There was no chance now that Christianity would spread eastward into the Arabian peninsula. Mecca would not be converted; the Quraysh tribe would continue to worship at the Ka’aba; and the children of the Quraysh tribe, including a six-year-old boy later known simply as Muhammad, would not grow up under the cross.

13

Justin II made no effort to challenge Khosru’s meddling in Arabian politics. In fact, he appears to have been losing his mind. John of Ephesus says that he used to bite people when he was angry with them, and that he was only soothed when his courtiers let him sit in a little wagon and pulled him around the palace in it.

14

It had been a long time since the empire had suffered from an insane emperor: for decades, the throne had been held by the fit and the shrewd. Justin’s wife Sophia, niece of the legendary Theodora, convinced Justin to name the able courtier Tiberius to be his Caesar. Justin II agreed, and until the emperor died in 578, she and Tiberius controlled the empire together. After Justin’s funeral Tiberius was crowned emperor; Sophia offered to marry him if he would divorce his wife, but he declined.

15

In 579, one year later, Khosru of Persia died after a forty-eight-year reign. Despite his abandonment of the Mazdakite creed, Khosru had worked hard to make his empire just.

*

The later historian al-Tabari, eulogizing him, lists Khosru’s reforms: children with questioned paternity must nevertheless be given their fair inheritance; women married against their will could choose to leave their husbands if they wished; convicted thieves should make restitution, not merely suffer punishment; widows and orphans must be provided for by relatives and by the state. He had also conquered new territory and equipped Persia with a strong infrastructure of canals and irrigation conduits, rebuilt bridges and restored villages, well-maintained roads and well-trained tax officials and administrators, and a strong army.

16

But the deaths of the two great emperors, Justinian and Khosru, closed an era for both empires. Byzantium had already begun a downward slide; whether Persia could remain strong without its great king at the helm remained to be seen.

Between 558 and 656, the lands of the Franks divide into three realms, and the Merovingian kings slowly give up their power

B

Y

558,

THE FOUR-WAY RULE

of the Franks had once again become a single kingship. Illness and murder had removed three of Clovis’s heirs, and the last surviving son, Chlothar I, now ruled, like his father, as king of all the Franks.

This second unification of all the Franks under one crown lasted exactly three years. In 561, Chlothar came down with a high fever in the middle of a hunt. He died not long after, after a half-century reign, and left the crown to all four of his surviving sons.

His struggle against his own brothers had not convinced him to name a single heir. The old ideals of the Frankish warrior-chiefs survived: the king should earn his spurs, not merely inherit them. Chlothar had won his crown by outlasting, outwitting, and outfighting his brothers, and none of his four sons would get a free pass into the high kingship of the Franks.

The four brothers realized that they were in competition, and from the day of their father’s death they behaved, not as joint rulers, but as separate kings of neighboring and sometimes hostile states.

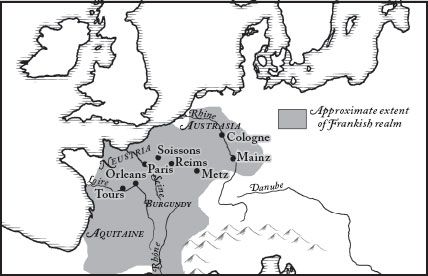

When the second oldest brother, Charibert, died in 567, the three remaining kings seized his territory, and the Frankish kingdom assumed a three-way division that would dictate its politics for the next century. The northern territory, ruled by Sigebert, was known as Austrasia; its capital was originally the city of Reims, but Sigebert moved his seat to Metz, closer to the border, to guard against the invasions of wandering Avars. Guntram ruled over Burgundy, which had been folded into the Frankish territory some years before; Chilperic controlled the central and southern Frankish lands, a territory known as Neustria, which contained the cities of Soissons and Paris.

Burgundy was the minor of the three kingdoms; Neustria and Austrasia were almost equal in land and in strength. Both Chilperic of Neustria and Sigebert of Austrasia had an eye on the high king’s seat; Sigebert decided to up his chances by making a match with the Visigothic princess Brunhilda, daughter of King Athanagild.

34.1: Territories of the Franks

Athanagild agreed to the marriage and sent Brunhilda from her home in Hispania, along with a large dowry. When he heard of the match, Chilperic of Neustria realized that his brother had pulled ahead of him in the power race. “Although he already had a number of wives,” Gregory of Tours writes, “he sent to ask for the hand of Galswintha, the sister of Brunhilda.” He also promised that he would put all his other wives away if King Athanagild would agree to the match.

1

The king of the Visigoths must have thought he had hit the jackpot. He sent Galswintha off after her sister, and when she arrived at the court of Chilperic, he kept his promise and honored her as his only wife: “He loved her very dearly,” Gregory writes, deadpan, “for she had brought a large dowry with her.”

But Galswintha soon discovered that her husband was actually still very much in love with one of his previous wives, a woman named Fredegund, who in spite of having been formally put away still showed up in the royal bedchamber on a regular basis. She complained; he insisted; she asked to go home; he refused; and finally, one morning, she was found strangled in bed. The court poet Venantius Fortunatus, who wrote the lament over her death, had to choose his words with great care. He describes the marriage and then goes straight from life to death without pausing to describe the hows and whys. “Enjoying for so short a time the binding relationship with her husband,” he explains, with tact, “she was snatched away by death at the start of her life.”

2

Both her husband Chilperic and her rival Fredegund were suspected of doing the snatching, or at least of arranging it. There was no proof (even though Chilperic now brought Fredegund back to court as his queen), and both escaped without penalty. But Brunhilda, now queen of Austrasia, never forgave or forgot the murder of her sister.

Seven years of inconclusive war followed, with none of the brothers managing to make significant gains on the others. Chilperic and Sigebert were always enemies, but Guntram, with his smaller territory, changed allegiances back and forth, depending on who seemed less likely to try and kill him. Finally, in 575, Fredegund (now queen of Neustria) sent two assassins to kill Sigebert in his palace. They pretended to be traitors from Chilperic’s court, willing to change sides and recognize Sigebert as king, but when they got into Sigebert’s presence they attacked him with poisoned scramasaxes—long Scandinavian knives normally used not as weapons but as eating tools.

3

Sigebert died in agony when the poison did its work, leaving his five-year-old son Childebert II as his heir and his wife Brunhilda as regent. Brunhilda now had double reason to hate her sister-in-law: Fredegund, she believed, was responsible for the deaths of both her sister and her husband.

She took good care of her son’s realm; she convinced his uncle Guntram, who was childless, to adopt the boy as his own. This made young Childebert II both the king of Austrasia and the heir of Burgundy, and would allow him to combine the two realms after Guntram’s death.

She also supervised the day-to-day administration of Austrasia. Brunhilda turned out to be a thoroughly competent ruler—so much so that the Frankish nobles were annoyed by her. Her force of personality and the Frankish hostility to her survive in the later Germanic epic called the Song of the Nibelungs, in which she is brought from afar (Iceland, in the case of the story) to become the wife of the German king. His friends advise against it: “This queen,” his friend Sigfrid tells him, “is a thing of terror.”

4

But despite the Frankish hostility to his mother, Childebert II refused to send her away even when he reached his majority; he kept her at court as his advisor.

Fredegund, over in Neustria, intended to be just as powerful as her sister-in-law. Chilperic was murdered in 584 by a man with a personal grudge; he had no son, but right after the funeral, Fredegund announced that she was pregnant with her husband’s heir.

This announcement was greeted with skepticism. In fact, once the baby was born, Guntram (who was normally mild-mannered; his chronicler Fredegar calls him “full of goodness”) suggested publicly that the child’s father was a Frankish courtier, rather than his dead brother. At this, Fredegund rounded up three bishops and “three hundred of the more important leaders. They all swore an oath that King Chilperic of Neustria was the boy’s father.”

5

Guntram was forced to back off. He was too good a man to go against the word of a bishop, and so he went to Paris for the child’s baptism. Fredegund named the little boy “Chlothar II,” after his powerful (putative) grandfather, and ruled over Neustria as his regent.

In 592, Guntram of Burgundy died and left his part of the Frankish rule to Childebert II of Austrasia, his nephew and adopted son. This meant that Brunhilda was now helping her son to rule over both Austrasia and Burgundy, while Fredegund was acting as regent over Neustria. The Frankish rule had devolved to these two powerful women, the Frankish Fredegund and the Visigothic Brunhilda, who loathed each other with a deep, personal hatred—and who had the power to determine the actions of their kingdoms.

Neither woman would allow that power to slip from her hands. Brunhilda’s son, Childebert II, died in 595; he was only in his mid-twenties, and Brunhilda at once accused Fredegund of poisoning him from a distance. His death, though, put her squarely back in control of the double realm of Austrasia and Burgundy. She became regent for his two young sons, aged nine and eight, who divided Austrasia and Burgundy between them.

Fredegund and her son, Chlothar II, immediately tried to seize Paris. The battle, says the Frankish chronicler Fredegar, created “great carnage” but didn’t accomplish much of anything. The hatred between the queens might have swelled into a full-fledged war that would have destroyed the kingdoms of the Franks, but the following year, Fredegund died, and her son began to rule alone.

6

Two years later, the dead Childebert’s older son, Theudebert II of Austrasia, reached the age of thirteen. He could legally rule alone, and so he kicked his grandmother Brunhilda out, to the loud cheers of the Austrasian nobles. The old woman made her way south into Burgundy, hoping to join her younger grandson Theuderic II there, but apparently got lost on the way: “A poor man found her wandering alone,” Fredegar says, “and took her, at her request, to Theuderic who made his grandmother welcome and treated her with ceremony.”

7

The Frankish kingdom had once again become three independent, essentially hostile realms. In 599, Chlothar II of Austrasia, now a precocious fifteen, tried to attack his cousins and get their land; but the two brothers decided to form a united front. They combined the armies of Burgundy and Neustria, defeated Chlothar II, and took much of his territory away, dividing it among themselves.

Burgundy, Brunhilda’s new home, was growing in size and strength, and Brunhilda went back to her high-handed ways; the chronicler Fredegar says that she had at least one nobleman accused of treachery and put to death so that she could claim his land for the throne, and also accuses her of plotting the assassinations of various other powerful officials. Theuderic himself, once he turned thirteen in 600, was unable to get rid of his grandmother and rule Burgundy on his own. He had welcomed her in; in return she had attached herself to the power of the throne like a limpet. By the time Theuderic had turned twenty, well past the age when a king might be expected to marry and sire an heir, he was still single and still under his grandmother’s thumb.

Unable to throw her out, reluctant to ask his brother in Austrasia or his cousin in Neustria for aid (he was the youngest of the three, and perhaps was afraid that opening the door to either might end with his losing the throne), he sought a new ally. In 607, he sent an ambassador to Hispania and asked the Visigothic king Witteric for the hand of his daughter Ermenberga.

The Visigothic kingdom was at its height, and a Visigothic-Burgundian alliance would have made Burgundy the strongest of the three Frankish kingdoms. But apparently Brunhilda could not bear the thought of losing her position as queen of the court. According to the historian Fredegar, she “poisoned him against his bride” with her words. Brunhilda was a crafty and resourceful woman, and by the time Ermenberga arrived, Theuderic had lost his taste for the whole project. He never even consummated the marriage and a year later sent his wife back to her father.

8

Instead, he made an alliance with his cousin Chlothar II of Neustria against his brother, Theudebert II of Austrasia, and in 612, the joint force attacked Theudebert’s army on the edge of the Forest of Ardennes. “The carnage on both sides was such that in the fighting line there was no room for the slain to fall down,” Fredegar’s account tells us. “They stood upright in their ranks, corpse supporting corpse, as if they still lived…. The whole countryside was strewn with their bodies.” Theuderic and Chlothar marched to Cologne, took Theudebert’s treasure, and captured Theudebert. A soldier, Fredegar adds, took Theudebert’s young son and heir “by the heels and dashed out his brains on a stone.”

9

Brunhilda had not forgotten her older grandson’s decision to throw her out of his court. She ordered Theuderic to imprison his brother and then had the young king murdered in prison. Theuderic claimed Austrasia as his own, making him joint king of Austrasia and Burgundy, but he died of dysentery less than a year later—still without a legitimate heir.

To keep the kingdom from falling into Brunhilda’s hands, the two mayors of the palace—Warnachar, mayor for Austrasia, and Rado, mayor for Burgundy—took action.

“Mayor of the palace” was the Frankish title for the king’s right-hand man, the official who took care of the royal estates, supervised the other government offices, and generally acted as prime minister and household steward combined. When the king was a child, or weak, or dead, his mayor ran the realm.

Neither Warnachar nor Rado wanted to see their domains taken over by Brunhilda, so together they invited Chlothar II to invade. In 613, he accepted the invitation and marched in, largely unopposed. He captured his aunt Brunhilda and put her to death in a particularly prolonged fashion: “He was boiling with fury against her,” writes Fredegar in his chronicle. “She was tormented for three days with a diversity of tortures, and then on his orders was led through the ranks on a camel. Finally she was tied by her hair, one arm, and one leg to the tail of an unbroken horse, and she was cut to shreds by its hoofs at the pace it went.”

10

Once again, the Franks were under a single rule: that of Chlothar II, the only one of the kings who probably had no actual relationship to the royal family.

Chlothar II began to try to bring some sort of order to the chaotic landscape. In 615 he issued the Edict of Paris, which among other provisions promised that the king of the Franks would not try to overrule the authority of the local palaces of Austrasia, Neustria, and Burgundy. The three Frankish kingdoms would be united under Chlothar, but there would be no single centralized government, and the offices of mayor would not be combined into one. Instead, each mayor of the palace would continue to administer his own realm.

11