The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (73 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

T

HE IMAGE OF

S

HIVA

had fallen in the north; but in the south, the god’s devotees were gaining power.

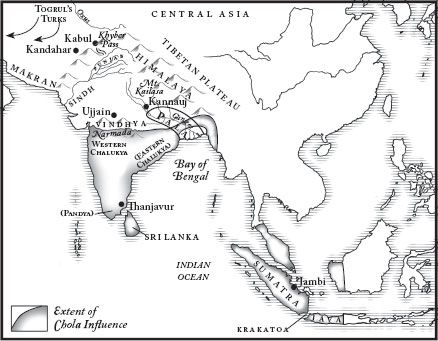

The Chola kings, devoted to the worship of Shiva and his goddess consort, had allowed most of their realm to slip through their fingers. Now, like the northern Ghaznavids, the Chola inherited an ambitious leader. Rajaraja I, who came to the throne in 985, began to lead his armies in the reconquest of the south. He wiped out the southern kingdom of the Pandya, which had revived itself under a line of pretender kings; he defeated the Eastern Chalukya and made them his vassals; he fought against the powerful Western Chalukya, forcing them to halt their own spread to defend their borders; he sent his men over the strait to the island of Sri Lanka.

Western Chalukya inscriptions accuse the Chola army of atrocities: the slaughter of women and children, the massacre of priests, rape and pillage and plunder. But the ruthlessness of Rajaraja’s conquests sent the Chola back up the rotating wheel of royal fortunes. “Having subdued in battle the Ganga, Kalinga, Vanga, Magadha, Aratta, Odda, Saurashtra, Chalukya and other kings, and having received homage from them,” the royal inscriptions boast, “the glorious Rajaraja, a rising sun…ruled the earth whose girdle is the water.”

12

He didn’t quite rule the earth, but after thirty years of fighting, he dominated the south. To commemorate the extent of his triumphs, he built a huge temple in his capital city Thanjavur: a temple devoted to Shiva, with three hundred priests dedicated to the service and worship of the god and fifty musicians who were salaried to sing the sacred liturgies. A mighty lingam—a seamless pillar with no features, a representation of the all-encompassing, transcendent essence of Shiva, more powerful and more sacred than the image that had fallen in the north—stood at its center. On the walls were painted scenes of Shiva as conqueror, Shiva as destroyer of cities.

13

Rajaraja’s son and commander Rajendra succeeded him in 1014 and ruled, like his father, for three full decades. This second long reign, following on the first, achieved what the Ghaznavids up north had failed to do: establish a hold on the conquered land that outlasted the death of its founder. Like his father, Rajendra was a vicious and skilled fighter. He “reduced to ashes all the kings who stood aloof from him,” his inscriptions tell us, “wrought ruin, annihilated the country.”

14

Rajendra’s great achievement was to set sail. He sent trade ships east to the court of the Song, carrying elephant tusks, frankincense, aromatic woods, and over a thousand pounds of pearls. He also sent warships across the southern strait, carrying naval forces to the island of Sri Lanka. There, he claimed to have captured “the lustrous pure pearls…the spotless fame of the Pandya king”—the crown and regalia of the legitimate Pandya line, which had rested on the island since the Pandya flight there a century before, and which the Rashtrakuta kings had sought but failed to find.

15

He then began a two-year march up the coast of the Indian subcontinent, towards the lands of the Pala and towards the sacred mountain of Kailasa, where, as his own records tell us, “Shiva is residing.” He had captured the symbol of southern rule; now he was heading towards the residence of the god, the symbol of northern dominance. “His army crossed the rivers by way of bridges formed by herds of elephants,” his chronicles tell us. “The rest of the army crossed on foot, because the waters in the meantime had dried up, being used by elephants, horses, and men.”

16

72.2: The Spread of Chola Influence

When he arrived at the Ganges, he was faced by the armies of the Pala king. The once great Pala kingdom had shrunk from its former heights, but under its long-lived king Mahipala had begun to grow again. Mahipala had been on a conquering spree of his own, taking advantage of the preoccupation in the northwest with invading Ghaznavids to rebuild Pala power in the northeast.

Rajendra met Mahipala on the banks of the Ganges and won a great victory against him. But so far from home, he did not have the resources to follow up with an attempt at conquering the entire kingdom. Instead he pushed past it, across the Ganges delta, and forced the people along the coast to pay tribute.

Continuing on by land would have taken his army even farther away from the resources of the Chola heartland; it would have been simple for the Pala army (or another hostile force) to come from behind, breaching the thin strip of conquests along the coastline and cutting them off. Instead, Rajendra led his army back home and began to plan a naval expedition. It launched in 1025, sailing all the way across the Bay of Bengal to land on the coast of the kingdom of Srivijaya. Srivijaya, dominating the islands of Java and Sumatra, controlled the shipping routes into southeast Asia; the Chola armies, invading the island, collected tribute from the Srivijayan king and seized control of the routes.

By the time of his death in 1044, Rajendra left a southern empire that boasted tributaries all the way up to the north and far to the east. His son Rajadhiraja, grandson of the great Rajaraja, inherited his crown without chaos or struggle. Never before had a southern Indian kingdom ruled so much for so long. The traditional division of the south into separate realms had ended; Chola language, Chola power, Chola customs now blanketed the south of India and were spreading across the Bay of Bengal into southeast Asia.

17

The wealth of the court, gathered from conquered cities and from trade with the southeast, meant that the Chola kings could now afford to support poets and scholars at court. Under the patronage of Rajadhiraja and his successors, southern Indian literature bloomed. The poet Tiruttakadevar, composer of one of the most enduring southern epics, was from the same blood as the Chola royal house. His tale told of the prince Jivaka, skilled fighter and general, who earned a kingdom and then willingly gave it up; in victory, he had discovered the hollowness of all human achievement.

18

Between 976 and 1025, a steel-hard emperor rules in Constantinople, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is razed in Jerusalem, and the Abbasid caliphate denounces the Fatimids as heretics

T

HE DEATH OF

J

OHN

T

ZIMISKES

from dysentery left young Basil II, at seventeen, as senior emperor in Constantinople. His sixteen-year-old brother Constantine VIII ruled as co-emperor, but the government belonged to Basil; Constantine spent most of his time hunting, with an occasional diplomatic mission interrupting his free time. “Basil,” the medieval biographer Michael Psellus tells us, “always gave an impression of alertness, intelligence, and thoughtfulness; Constantine appeared to be apathetic, lazy, and devoted to a life of luxury. It was natural that they should abandon the idea of joint rule.”

1

Basil II had been a crowned emperor since toddlerhood. Now for the first time he had actual power, and the first trouble spot he had to deal with was Bulgaria. John Tzimiskes had annexed Bulgaria, but he had been able to control only the east of the country. Freedom fighters in the west, led by four brothers with the biblical names of David, Moses, Aaron, and Samuel, were agitating for independence.

They claimed that they wanted the release of their imprisoned king Boris II, who along with his brother and heir Romanus had been tossed into jail by John Tzimiskes. Basil II suspected that the oldest brother, the freedom-fighter Samuel, was more interested in Bulgaria than in Boris. He decided to appeal to everyone’s worst instincts. In 981, he set Boris II and Romanus free. By this point, at least two of the Bulgarian brothers had died in battle, and Samuel was in sole charge of the resistance. Basil hoped that if the royal family actually returned to Bulgaria, Samuel would be forced to admit that he was only using them as a useful rallying point. Then, a civil war might break out and bring the independence movement to a messy end.

Romanus and Boris II made their way back to the west of Bulgaria, as planned; after that, things went to seed quickly. They were challenged by a border guard, and before they could identify themselves, the guard killed Boris II. Romanus managed to convince the guard of his identity and survived.

2

This turned out as well as possible for Samuel. Boris II would have claimed the throne and ruled on his own, but Romanus proved more amenable. Even more conveniently, he had been castrated during his imprisonment, so there would be no royal offspring. Samuel declared Romanus to be king of Bulgaria and simply kept power in his own hands, a turn of events that makes one wonder about the “accident” at the border.

3

Basil had been right about Samuel’s motivations, but this was not exactly the outcome he had hoped for. Now Samuel began to fight his way into Thracia, capturing Byzantine towns for his own. He also put his only remaining brother to death. Clearly he was positioning himself to claim the title “Emperor of Bulgaria.”

Unfortunately, Basil’s ability to strike back was hampered by ongoing domestic troubles. His general Bardas Phocas—a man of royal blood, the nephew of Nikephoros Phocas—convinced the troops in Asia Minor to declare him emperor. Bardas Phocas was a formidable opponent; Michael Psellus describes him as a man who believed life had wronged him, “always wrapped in gloom, and watchful, capable of foreseeing all eventualities…thoroughly versed in every type of siege warfare, every trick of ambush, every tactic of pitched battle…. Any man who received a blow from his hand was dead straightaway.” In comparison, Basil II was less impressive: “He had just grown a beard,” Psellus writes, “and was learning the art of war from experience in actual combat.”

4

While Samuel was systematically ripping away chunks of land from the western border, Basil was forced to mount an attempt to remove Bardas Phocas in the east. His overextended army was too thin to face Phocas’s loyal Asia Minor troops, so he asked his brother-in-law Vladimir of Kiev, prince of the newly Christian Rus, to supply reinforcements. Vladimir sent him six thousand Rus soldiers: “These men,” says Psellus, “fine fighters, he had trained in a separate corps.” The Rus didn’t mix well with the Byzantine army, but on their own were a fierce and powerful company.

5

In April 989, Basil led his combined Byzantine and Russian forces into battle against Bardas Phocas at Chrysopolis. The general prediction seems to have been that Bardas Phocas would mop him up, despite the Rus reinforcements. But as Bardas Phocas led his supporters towards the imperial line, he fell dead from his saddle, victim of either stroke or poison. His army disintegrated at once and fled; Basil’s men chopped up the body with their swords and brought the head to Basil.

The young emperor’s throne was temporarily safe, but Michael Psellus tells us that his personality changed drastically after this time: “He became suspicious of everyone, a haughty and secretive man.” He had discovered that to be emperor was to be always on guard, always alert, and never trusting.

He decided not to send his Rus tribute fighters home. With Vladimir’s consent, he kept them close to him: like the Abbasid caliphs, he now felt the need for a personal guard from outside the empire, a guard that would be less vulnerable to recruitment by would-be conspirators. These Russian bodyguards became known as the Varangian Guard. They would remain in the emperor’s confidence, and in his personal service, his most trusted companions in a world filled with traitors.

His opinion of his own people was not improved when another general, Skleros, picked up the banner of Phocas’s rebellion. Unlike Phocas, Skleros decided not to risk an out-and-out battle for supremacy. “His idea was rather to…harass the enemy by guerilla tactics without committing himself to open warfare,” Psellus writes. Basil’s transports were halted on the roads, shipments to and from Constantinople were seized, royal couriers waylaid and their orders stolen. The emperor was unable to quell the guerilla revolt, which dragged on into the next year and then the year after, constantly distracting him from his plans to launch a full-scale invasion of Bulgaria.

*

Finally Basil took the pragmatic path and offered Skleros a deal. If the general would call off his forces, give up his claim to the crown, and retire to the countryside, Basil would grant him the rank of second in the empire and give all of his supporters immunity. Skleros was growing old; by now he was walking with difficulty, relying on bodyguards to help him move, and he accepted the emperor’s bargain.

Michael Psellus says that Basil then asked Skleros, as an experienced general and the leader of a successful rebellion, for advice: how could he preserve the empire from dissension in the future? Skleros answered with searing honesty. “Cut down the governors who become overproud,” he said. “Let no generals on campaign have too many resources. Exhaust them with unjust exactions, to keep them busied with their own affairs…. Be accessible to no one. Share with few your most intimate plans.”

6

The counsel matched Basil’s own inclinations: to be private, withdrawn, and thoroughly in control. As he turned to face the external threats to his rule, he extended an autocratic control over the internal affairs of the empire, standing entirely alone at the top. “He alone introduced new measures, he alone disposed his military forces,” Psellus writes. “As for civil administration, he governed, not in accordance with the written laws, but following the unwritten dictates of his own intuition…. All his natural desires were kept under stern control, and the man was as hard as steel.” He campaigned year-round, fighting throughout the cold of winter and the heat of summer: “His ambition,” Michael Psellus concludes, “was to purge the Empire completely of all the barbarians who encircle us and lay siege to our borders, both in the east and in the west.” Any anger, any disappointed desire for loyalty, came out in his campaigns against his enemies on the outside.

7

Those enemies lay on both the eastern and western horizons. Battling on in Bulgaria, Basil’s army managed to capture Romanus and haul him back to Constantinople. This had almost no effect on the Bulgarian war, which just went to show how irrelevant Romanus was (and had always been). Samuel, who had been in control for decades, simply remained at the head of the Bulgarian army. Nevertheless, he waited until Romanus died in captivity to claim the title of king for himself. With Samuel’s coronation, the dynasty of Krum came to an end.

But Basil was now forced to leave the Bulgarian front in the hands of his generals (something that went against his inclination to stay in complete control). His presence was desperately needed in the east, where the Muslim threat had once again grown worrisome.

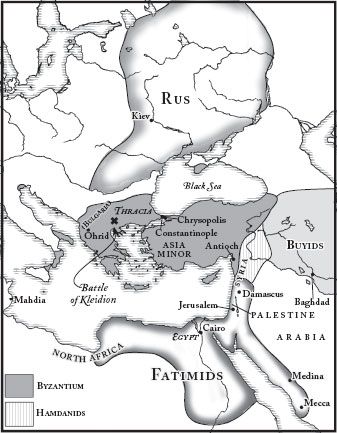

It came not from any of the smaller kingdoms that had fragmented the east, but from the Fatimids of North Africa. In the decades since al-Mahdi’s declaration that he, and only he, was the legitimate leader of the Muslim people, the Fatimid domain had spread eastward from its North African birthplace. By 969, the Fatimids had finally managed to seize control of Egypt; there, the Fatimid caliph al-Muizz directed that the foundations of a new Fatimid city be laid in his new territory. He moved his palace to this new city, which was named Cairo. By 973, the balance of Fatimid power had shifted so far to the east that Cairo had become the functioning capital of the empire, and the Fatimid caliph had lost control of the North African tribes in the Maghreb.

Under the command of al-Muizz’s son, al-Aziz, Fatimid armies spread across the Red Sea into Arabia and took control of the holy cities Medina and Mecca. Fatimid soldiers marched up into the Abbasid-held provinces of Palestine and Syria and, in a year of savage campaigning, conquered both.

Basil’s counterattack began in 995. He led a massive push into Syria and managed to recapture much of the land that had fallen to the Fatimid armies. His year-long campaign fell short of Jerusalem, which remained in Fatimid hands, a failure that would throw a very long shadow indeed; but Basil was not unhappy with the outcome. When al-Aziz died in 996, his eleven-year-old son, al-Hakim, was appointed caliph in his place. Basil sent to him, suggesting that they negotiate a peace. He had retaken most of his Syrian lands, and he wanted to return to the fight on the western border.

73.1: The Fatimid Caliphate and Byzantium

Al-Hakim and his advisors agreed to a treaty. The terms were finally concluded in 1001, and the war on the eastern frontier halted for ten years. Basil rode back to the west to fight against Samuel.

But after four years of slow, painful advance and retreat, the Byzantine front had progressed only halfway across Samuel’s territory. Basil decided that it was time for a breather. In 1005, he returned to Constantinople to take care of domestic business; his generals held the frontier in place while Samuel remained pinned in the west. For some years the Bulgarian war was suspended.

8

Meanwhile, the young Fatimid caliph al-Hakim was tightening his hold over his empire in his own way. He was a deeply pious man who wished to establish himself as the perfect Muslim ruler: just and lawful, austere in his personal life and generous in public. But his piety led him into a series of decrees that, although reasonable enough from his own perspective, sounded harsh and meaningless to the many non-Muslims who lived inside his borders. He ordered vineyards destroyed, so that wine (forbidden to Muslims) could not be made anywhere in his realm; he decreed that women in Cairo remain in their homes, to protect their virtue; he commanded that the marketplace in Cairo be lit and open all night, demonstrating the complete peace and safety of his realm even in the dark (and forcing merchants to grab sleep throughout the day whenever possible).

9

Like Basil, al-Hakim was a man who closed his hand tightly over the internal workings of his kingdom; and over the ten years of the treaty, he grew increasingly worried about the non-Muslims within the Fatimid kingdom. In 1003, he ordered the church of St. Mark just south of Cairo razed, flattened the Jewish and Christian cemeteries around it, and built a mosque where the complex had stood. Throughout Egypt, Christian land was confiscated, crosses destroyed, and churches closed. And then, to discourage pilgrimage to Jerusalem, al-Hakim ordered the great Christian complex built by Constantine destroyed: the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, which protected the tomb of Jesus, commemorated as the site of the resurrection, and Golgotha, the hill of crucifixion. The enormous stones were hacked to bits with axes, and the rock itself was removed from the city.

10

From the patriarch of Constantinople and the pope in Rome down to the man on the street, Christians were aghast. But Basil, the nearest Christian ruler, refused to take immediate revenge for this act, since the treaty bound him to peace. He was getting ready to reignite the war against the Bulgarians, and a full-scale invasion of the Fatimid realm would have occupied all of his attention.

Matters grew worse when al-Hakim ordered the Jerusalem synagogue destroyed, early in 1011. Basil still declined to intervene, but the Muslims to the east used al-Hakim’s actions to denounce the entire Fatimid regime. The Abbasid court at Baghdad put out a decree under the name of the current Abbasid caliph, al-Qadir, officially (and vehemently) denying the legitimacy of the Fatimid caliphate. This “Baghdad Manifesto” was read out loud in mosques all throughout the Muslim world; it wrote into law the breach between the Fatimid and Abbasid caliphates.

11