The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (32 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

Between 551 and 579, the Lombards seize Italy, the Persians push into Arabia, and both Justinian and Khosru leave their kingdoms to lesser heirs

I

N

C

ONSTANTINOPLE

, the plague had finally died away. A five-year truce with the Persians protected the eastern border. At last, Justinian could turn his attention back to his project of conquering the west.

The Byzantine army in Italy was stretched to its limits and would not be able to hold out much longer, so Justinian sent the soldier-eunuch Narses (Belisarius had recently retired from active duty) to Italy with instructions to hire mercenaries from the Gepids and the Lombards.

Both of these tribes had already agreed to settle along the northern edge of the country, but the Lombards proved easier to recruit for actual fighting. The Lombards had probably come, long ago, from the cold northern lands on the far side of the Baltic Sea, known to ancient historians as Scandia. Their own oral history (set down by Paul the Deacon in the eighth century, hundreds of years later) testifies to this origin: “The peoples [of Scandinavia]…had grown to so great a multitude that they could not now dwell together,” Paul writes, “so they divided their whole troop into three parts, as is said, and determined by lot which part of them had to forsake their country and seek new abodes.” The Lombards, one of those three bands, had been forced by chance to set out for a new home.

1

When Narses arrived in Italy around 551, he promised the Lombards new land in Pannonia in exchange for their help. With the Lombard reinforcements behind him, he picked up the war against the Ostrogoth resistance. Their king Totila had recaptured Rome and mounted his defense there, rather than at Ravenna, but Narses’s mercenaries numbered almost thirty thousand men: he had recruited not only Lombards but also a few Gepids and opportunistic Huns. When Narses attacked Rome, six thousand Ostrogoths died in battle, and Totila was killed.

2

The Goth nobles elected another king, but he too fell in battle. Narses and his mercenaries recaptured Ravenna and re-established a Byzantine capital there. The Ostrogoth domination had ended; now Italy would be ruled, on behalf of the emperor Justinian, by a Byzantine official called an exarch, a general who also had authority to administer civilian affairs. Constantinople had regained the heart of the empire—but only after years of war that had destroyed the countryside, wrecked the cities, and impoverished the people.

3

In 552, Justinian also regained control of southern Hispania. The Visigothic king had been murdered, and the court was in disarray; one of the nobles, Athanagild, sent a message to Constantinople, appealing (unwisely) for help in seizing the throne. Byzantine ships arrived to support him and Athanagild got his throne, but by 554, Byzantine armies had captured ports and fortresses all along the southern coast, and Justinian was able to establish a Byzantine province there with Cartagena as its capital.

4

In the wake of the plague, Justinian was finding victory. He was on the edge of rebuilding the old Roman empire, restoring the old glories; Byzantine administration now reached to the western edge of the Mediterranean; Rome was again his.

But at once new challenges arose in the east.

Y

ET AGAIN

, a new nation had formed itself out of a loose and disorganized tribal confederation. Over the previous century, nomads from northern China, known to the Chinese as the T’u-chueh, had made their way westward into central Asia. One of their warchiefs was named Bumin Khan, and in 552 he gathered his tribe and their allies together at a place called Ergenekon, in the Altay mountains, and declared himself their king. This declaration must have followed some years of conquest, although those are invisible to us; he also married a Chinese princess from the former Western Wei royal family, adding the sheen of royalty to his rough grasp of power, and established his capital at the city of Otukan.

The new state formed by Bumin Khan became known as the Gokturk Khaghanate, the first Turkish kingdom. Turkish legends gathered around the mountain stronghold where Bumin Khan created a people: Ergenekon, the ancestral homeland of the Turks, also became a paradise of sorts, a Garden of Eden within living memory.

5

Not long after the gathering at Ergenekon, Bumin Khan died and his son Mukhan took over the brand-new country. Mukhan began to fight the neighboring tribes to expand the Gokturk state, driving the nearest tribes—the nomadic Avars—westward towards Persia and Byzantium.

6

In 558, the displaced Avars reached the Byzantine borders, forcing Justinian to buy them off. They kept on going west and finally settled near the Danube, just east of the Gepids. They were not the only peoples disturbed by the new Turkish nation; Mukhan managed to conquer the eastern tribes of the Bulgars, agitating the remaining tribes who lived on the western shores of the Don river. Some of them crossed into Byzantine land, but rather than paying them off as well, Justinian recalled Belisarius from his retirement and sent his most experienced general to drive them away.

7

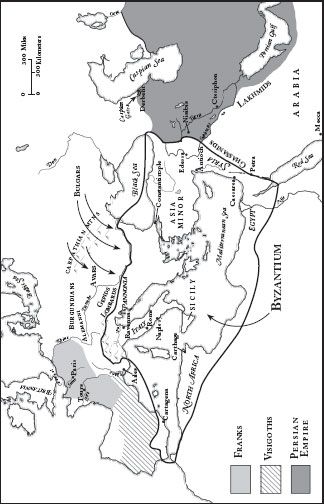

33.1: Byzantium’s Greatest Extent

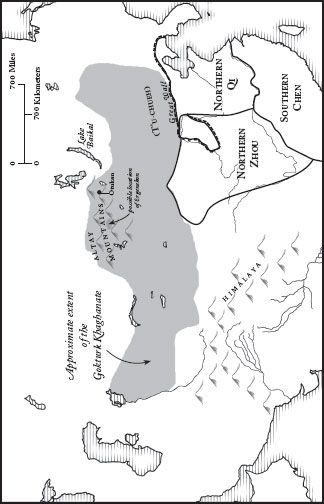

33.2: The Gokturk Khaghanate

He succeeded—which aroused all of Justinian’s old suspicions of his lifelong colleague. Even after decades of reign, Justinian must have felt his throne to be insecure. In 562, he accused Belisarius of corruption and jailed him; the following year, he relented, released his old friend, and pardoned him. It was the last skirmish between the two. Both men died in 565; Justinian was eighty-three, Belisarius sixty.

When Justinian drew his last breath, so did any chance that the Roman empire might be revived. Theodora had died childless in 548, probably of cancer, and Justinian had never remarried; he had no sons. His nephew Justin became emperor in his place. Almost at once, the new conquests in the west began to fragment.

33.3: Lombard Italy

In Italy, Byzantine domination was threatened by the arrival of plague in the year after Justin II’s accession. Paul the Deacon describes the characteristic swellings in the groin, the high fever, the stacks of unburied corpses, Italy emptied and vulnerable. “The dwellings were left deserted by their inhabitants, and the dogs only kept house,” he wrote.

You might see the world brought back to its ancient silence: no voice in the field; no whistling of shepherds; no lying in wait of wild beasts among the cattle; no harm to domestic fowls. The crops, outliving the time of the harvest, awaited the reaper untouched; the vineyard with its fallen leaves and its shining grapes remained undisturbed while winter came on; a trumpet as of warriors resounded through the hours of the night and day; something like the murmur of an army was heard by many; there were no footsteps of passers by, no murderer was seen, yet the corpses of the dead were more than the eyes could discern; pastoral places had been turned into a sepulchre for men, and human habitations had become places of refuge for wild beasts. And these evils happened to the Romans only and within Italy alone.

8

Once the plague had died away, empty lands were left for the taking, and the Lombard king Alboin set his sights on them.

The territory in Pannonia had not been enough for his people. Their numbers had grown, in part because he had conquered both of the neighboring tribes, the Heruls and the Gepids (Paul the Deacon tells us that he killed the Gepid king in battle, married his daughter by force, and made a drinking goblet out of his head, a throwback to a much more ancient warrior custom). Now the Lombards numbered over a quarter of a million, and they needed more space.

9

By 568, Lombards were crossing en masse into Italy. In 569, Alboin and his Lombard warriors conquered Milan and began to storm southward. The Byzantine territory in central Italy fell quickly. Only the southern coasts and a strip of land from Ravenna down the coast, cutting across to Rome (where the pope, Benedict I, claimed the protection of the Byzantine emperor) remained in Byzantine hands. Italy had changed hands once again.

Meanwhile the Visigothic king Leovigild, brother and successor to Athanagild, had come to the throne of Hispania and was busy reconquering the land his predecessor had lost. Justin II was unable to organize a decent defense, let alone retake the disputed land. The Byzantine attempt to claim the old Roman lands had ended.

*

E

AST OF

C

ONSTANTINOPLE

, the Persian Khosru was having exactly the opposite experience. His conquests to the east (he had destroyed the Hephthalites some years earlier) had brought Persia to a high-water mark of power.

†

Khosru reorganized the now vast expanse of his land, dividing it into quadrants and placing a military commander over each: the far eastern land won from the Hephthalites, the central area of the kingdom, the lands to the west near the Byzantine border, and the southern Arabian territories.

10

In 570, Khosru was presented with the opportunity to expand his hold over those Arabian lands.

The kingdom of Axum was planning to cross the Red Sea and attack the Arabian city of Mecca.

*

Once again, the attack would take the form of a religious crusade: the king of Axum, Abraha, was Christian, and Mecca was the center of traditional Arabic religion. It was also vulnerable. There was no king in Mecca, no one able to organize and lead an effective defense. Arabs were loyal to the tribe of their birth; the tribe was their ethical center, which meant that loyalty did not extend outside of tribal boundaries. Raiding another tribe for food, animals, and women was a constant that bore no stigma of moral wrong. Arabia was a dry land of ever-colliding micro-nations. Mecca itself was governed by a council made up of heads of the leading families, all of whom had equal authority; the convention that no one was to draw a weapon in the sacred territory of the Ka’aba was the only acknowledgment that some greater force might bind the tribes together. There was no common law, no central authority, no acknowledged warleader. Even the strongest tribe in Mecca, the Quraysh, was divided, with three clans within it struggling for dominance.

11

Abraha of Axum assembled not only his armies and ships but also at least one elephant—the first time this beast had ever been used in Arabian warfare. He moved his forces across the Red Sea and prepared to lay siege to Mecca. But before he could bring the city down, his forces were felled by plague and he was forced to withdraw. His failure in the Year of the Elephant appears in the Qur’an, half a century later, as an intervention of God:

Didn’t you see how your Lord treated the troops with the elephant?

Did not God foil their strategy,

sending against them flocks of birds

pelting them with rock-hard clay,

making them like stubble of grain that’s been consumed?

12