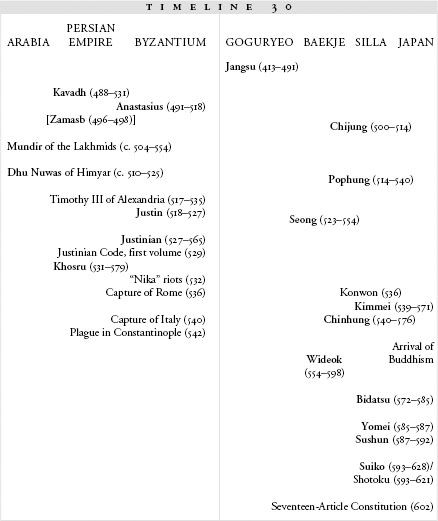

The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (30 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

Sushun, like his brothers, had been brought to the throne and maintained there by Soga influence. Unlike his brothers, he quarrelled with the kingmakers.

He fell out with the current chief of the Soga clan, Soga no Umako, who was also his uncle. “He hated his uncle for the high-handed way in which he ran the government as Great Imperial Chieftain,” the official chronicles tell us. “One day the head of a wild boar was presented to him, and the Sovereign pointedly asked when the head of his hated enemy would be brought in like manner.” Soga no Umako got word of this not-so-veiled threat and acted first; he sent an assassin to get rid of his royal nephew. At the same time, he led his clan in a concerted attack on the most powerful rival to Soga power: the anti-Buddhist clan of the Mononobe, allies of the equally anti-Buddhist Nakatomi family. When the dust had settled, the Mononobe had been badly defeated (although not destroyed) and Sushun was dead.

10

The senior claimant to the throne was a woman named Suiko, triply qualified to rule: she was a daughter of Kimmei and thus half-sibling to the previous rulers; her mother was from the Soga clan; and she had been not only the monarch Bidatsu’s half-sister, but also his wife. Soga no Umako wanted her on the throne: “He wanted someone he could control, so chose a woman,” the chronicles tell us. Alongside of her, he placed as regent yet another Soga relative: Shotoku Taishi, a Buddhist scholar who became the first true statesman of Japan.

11

Nineteen at his appointment in 593, the regent Shotoku hit his stride in his thirties. He sent envoys to the Chinese kingdom, demanding that the ambassadors be received as representatives of an equal and sovereign nation; in an attempt to diminish the power of the clan leaders, he instituted a Chinese-style set of government ranks, naming each rank after a cardinal virtue (such as fidelity, justice, and wisdom) in order to remind the officials that they were serving because of their character, not their birth. And he took it upon himself to create a written statement of the principles by which the Yamato dynasty held power. For the first time, the heavenly sovereign would move beyond the vague claim of divine sanction as he grasped his power.

The Seventeen-Article Constitution—the Jushichijo no Kempo—was issued in 602. It is not exactly a constitution in the western sense; it does not lay out a structure for government or restrict the power of the ruler. Instead, it lists the principles by which the Yamato monarchs should be ruling their country—and by which the people should agree to be ruled.

If the governing harmonize and the governed are hospitable, and matter accords argument, reason will find its way.

Upon the Imperial command, scrupulous obedience should be practised. The Lord is the Heaven, the subject is the earth. Therefore, the Lord speaks; the subjects obey. Disobedience leads to self defeat.

If the people observe decorum, the State will govern itself.

12

The Constitution reveals, in every line, the conviction that the monarch is the government, that the king is the law. If the king is law, there is no need for a written law to restrict him; there is simply the need, ongoing and prior to all else, that the ruler be moral and virtuous. The Constitution does not try to lay down law; it tries to define the moral character of the king, and also his people. All else should flow harmoniously from this.

It was an elegant and simple point of view: if the occupant of the royal palace was morally and spiritually pure, the country would be at peace. At its core, it was a political philosophy that denied Soga power. If the monarch was not only heavenly sovereign but also the embodiment of earthly law, there was no place in Japan for Soga maneuvering. By appointing Shotoku as regent, the Soga patriarch had inadvertently kicked away the underpinnings of his own power.

Yet, like the Mandate of Heaven, the Seventeen-Article Constitution also had a sting in its tail for the king. Loss of virtue meant that the spiritual power of law no longer inhered, that a heavenly sovereign who was not a righteous ruler was merely masquerading as rightful king. Loss of virtue meant that the ruler could be removed, in full compliance with the Constitution itself.

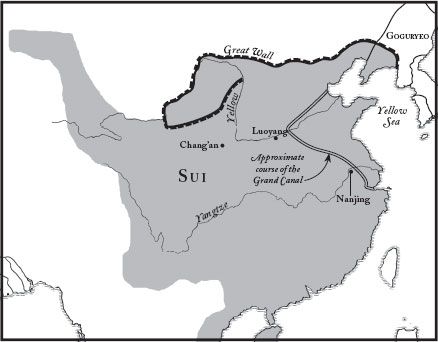

Between 546 and 612, the Sui dynasty brings the north and south back together, and the Tang dynasty reaps the benefits

A

CROSS THE OCEAN

, Liang Wudi of the Southern Liang tried again to enter a monastery and devote himself to enlightenment. He had been king of the Southern Liang for forty-five years; he was old, he was tired, and the wars in the outside world brought him no closer to peace. Again, his ministers paid a ransom to get him out, this one even larger. Again, Liang Wudi was forced to leave the monastery and go back to his palace.

Not long after his return to the throne, there was another turnover in power to the north. The general behind the Eastern Wei throne, Gao Huan, died. He had kept alive the fiction that a legitimate Wei ruler still sat on the throne by ruling from the shadows through a puppet-emperor with royal blood. It was a traditional strategy, one that preserved the myth of the heaven-selected emperor, but Gao Huan’s son had no patience with it. In 550, he deposed the puppet-emperor and announced that he was emperor, founder of a new dynasty: the Northern Qi. Two years after he took the throne, he had the former puppet-emperor and his entire family murdered.

Now the three dynasties that ruled in China were the Southern Liang, the Western Wei, and the Northern Qi. Of the three, the Western Wei and the Northern Qi were of northern blood, and the Southern Liang continued to view them as foreign.

The old hostility between “Chinese” and “barbarian” was far from dead. Southerns scorned northerners, while northerners were touchy and defensive about their “barbarian past.” The northerner Yang Xuanzhi wrote, in the sixth century, of a drunken southerner who says loudly to his friends, in the hearing of the palace master of the north, that the northerners are nothing but barbarians: “The legitimate imperial succession is in the South,” he sneers.

The northern palace master retorts that he wouldn’t live in the south for the world: “[I]t is hot and humid, crawling with insects and infected with malaria,” he snaps. “You may have a ruler and a court, but the ruler is overbearing and his subordinates violent. Our Wei dynasty has received the imperial regalia and set up its court in the region of Mount Sung and Luoyang. It controls the area of the five sacred mountains and makes its home in the area within the four seas. Our laws on reforming customs are comparable to those of the five ancient sage rulers. Ritual, music, and laws flourish to an extent not even matched by the hundred kings. You gentlemen, companions of fish and turtles, how can you be so disrespectful when you come to pay homage at our court, drink water from our ponds, and eat our rice and millet?”

1

This northern defense appealed to ritual, law, custom, learning, and divine sanction—every ancient tradition, bar bloodlines, that the south claimed as its own.

When the Northern Qi dynasty replaced its predecessor, though, one northerner decided to put away that hostility long enough to ally himself with the south. The general Hou Jing, who had served the Western Wei, decided that he had no future in the new regime. He sent a message to Liang Wudi, offering to hand over to the south thirteen former Wei territories and a sizable army in return for a high southern government post.

2

Liang Wudi accepted the offer, but when the promised promotion came through, Hou Jing found his new rank insufficient. He allied himself with another malcontent: one of Liang Wudi’s many sons, Jian, also unhappy with his preferment. Together, the two men assembled an army and marched to the Southern Liang capital, Nanjing (Jianking), where the old king was forced to defend himself against a long and brutal siege. Contemporary chronicles tell of the starving population chasing rats through the streets in hopes of getting a mouthful of meat, of soldiers boiling their own leather armor, trying to make it soft enough to eat.

Finally Liang Wudi surrendered to the inevitable. He opened the gates and let his son and former ally through. Jian deposed his father, sparing his life; but he imprisoned Liang Wudi and allotted him so small a daily allowance of food and water that the old man weakened and died. He was eighty-six years old, and since claiming the crown by force, he had tried to relinquish it on three separate occasions.

Jian, now Liang Jian Wendi, lasted barely a year before his co-conspirator Hou Jing murdered him. The general then fell in turn, when the dead king’s younger brother raised a rebellion against Hou Jing and cornered him in the palace. The memory of the horrible siege was still fresh, and the people of Nanjing enthusiastically ripped Hou Jing to pieces.

3

The younger brother then took the throne himself as Liang Yuandi, third king of the Southern Liang. Liang Yuandi was a scholarly man, a Taoist (unlike his father) with over two hundred thousand books in his personal library.

His

reign was less than three years long; one of his own nephews went north, gathered a northern army, and then came back south and threatened to besiege Nanjing again. Seeing that defeat was inevitable, Liang Yuandi turned on his books and burned them. Buddhism had not straightened his father’s path; Taoism had not delivered him.

The instability of the Southern Liang throne continued, with three emperors claiming the crown between 554 and 557. In 557, the short-lived dynasty ended when an army general named himself founder of the new Southern Chen dynasty. This one would last barely thirty years.

The north was in no better shape. The Western Wei also fell when another army officer pursued the same path: he deposed the king and named not himself, but his son, king of the new Northern Zhou. A few decades earlier, the Eastern Wei, Western Wei, and Southern Liang had governed; now the three kingdoms in China were the Northern Qi, the Northern Zhou, and the Southern Chen. In 577, the Northern Zhou absorbed the Northern Qi, and China was once again divided into two: the Northern Zhou and the Southern Chen, occupying almost the same territory as the old Bei Wei and Southern Liang kingdoms forty years before.

Assassination and usurpation had begun to snowball into custom. Legitimacy was clearly a myth on both sides of the Yangtze; for a time it had become clear that divine sanction went to the man with the biggest sword.

T

HE NORTH AND SOUTH

had now drawn themselves together into two separate kingdoms; the fracturing spin-off of separate realms had slowly reversed itself. But the Yangtze, wide and slow, lay between the ancient self-proud south and the ambitious newcomers to the north.

A southerner named Yan Zhitui, serving at the Southern Liang court, was forced to flee north when the Southern Chen deposed his employers. In his northern exile, cut off from his roots, he wrote down a set of rules for his sons to follow so that they would remember southern principles. “Whereas southerners maintain a dignified silence over family affairs due to respect for each other,” he warned, “northerners not only discuss these things loudly in public, but even ask each other questions about it. Do not inflict such matters on others. If some one else asks you such questions, give evasive answers.” Northerners resent criticism, he points out, while southerners prefer to

be

criticized so that they “can learn their failings and make improvements.” Southern women conduct themselves in privacy, but his sons should be cautious of women in the north, who “take charge of family affairs, entering into lawsuits, straightening out disagreements…. The streets are filled with their carriages, the government offices are filled with their fancy silks. Those in the North often let their wives manage the family. This,” he adds, with the disdain of the Chinese courtier for the barbarian, “may be the remnant of the customs of the Tuoba.”

4

Despite any lingering barbarian practices, Zhou Wu of the Northern Zhou had ambitions to reunite the whole country under his throne—something that had not been done since the collapse of the Jin dynasty, more than two centuries before. He was young, ambitious, sane. But just as he began to plan the conquest, he grew ill. He was on campaign when the sickness killed him at the age of thirty-five.

The honor of reuniting China would fall to one of his officials: Yang Jian, a man of his own age who had fought for him, had given his daughter to be the crown prince’s wife, and had been rewarded with the noble title “Duke of Sui.” Yang Jian, loyal to his emperor’s family, helped the dead king’s son—his own son-in-law, Zhou Xuan—ascend the throne of the north in 578.

Zhou Xuan was already nineteen; his father had sired an heir in his early years. Unlike his father, he did not have his eye on long-lasting glory. Instead he proved to be more interested in his immediate power. He began to call himself “The Heaven,” designating his courtiers as “the earth” he forced all of his officials to get rid of any ornaments or decorative clothing so that his own costume would stand out; he began to execute anyone who offended him; he went on lavish royal progresses through the countryside to demonstrate his power, leaving his father-in-law Yang Jian in charge at home. A year after his coronation, he made his own six-year-old son emperor in name, apparently to give himself more freedom to indulge in his pleasures, which included beating and raping the women of the court.

5

All this time, Yang Jian managed to keep the government running smoothly, which Zhou Xuan both relied on and resented: “As Yang Jian’s position and reputation rose ever higher,” the contemporary

Sui History

records, “the Emperor more and more regarded him with dislike.” He threatened to execute his wife, Yang Jian’s daughter, and began to plan the assassination of Yang Jian himself.

6

Fortunately for the northern Chinese, the wayward emperor had a stroke and died in 579, at the age of twenty. Yang Jian, seeing his old friend’s kingdom in danger of falling apart, took immediate steps. He forged a document making him regent for the new emperor, his seven-year-old grandson Zhou Jing, and began to form an inner circle that could help him establish himself as the new ruler of the north.

Among his familiars were a competent general named Gao Ying and a great writer named Li Delin; Gao Ying helped him wipe out opposition to his regency, while Li Delin wrote beautifully convincing political rhetoric about Yang Jian’s right to rule. In September of 580, the child emperor signed an edict giving official praise to Yang Jian’s worthiness: it acknowledged him as “Supreme Pillar of State, Grand State Minister, responsive to the mountains and rivers, answering to the emanations of the stars and planets. His moral force elevates both the refined and the vulgar, his virtue brings together what is hidden and what is manifest, and harmonizes Heaven and Earth.”

7

Like so many soldiers before him, Yang Jian was in search of more than just power. Over the last decades, mere conquest had produced short-lived unstable kingdoms. He was after a lasting empire, and that meant he needed the Mandate of Heaven.

The edicts continued. In October, Yang Jian gave his grandfather, father, and great-grandfather posthumous royal titles. In December, he made himself a prince, a higher rank than any other noble at court. In January of 581, an edict of abdication appeared: more of Li Delin’s words, again with young Zhou Jing’s signature at the bottom. Yang Jian made the customary demur, refusing three times to take the title, but was eventually “persuaded” to ascend the throne as Sui Wendi, emperor of the north. He declared his rule the beginning of a new dynasty: the Sui, rightful rulers of the north.

8

He then made sure that the Mandate of Heaven would be unchallenged by murdering fifty-nine members of the Northern Zhou ruling family. Among them was his grandson, who died in July “at the will of the Sui.”

9

In 582, the king of the Southern Chen died and was succeeded by a dissolute and extravagant son, and the new Sui emperor saw his chance to begin the reunification.

He spent a careful seven years preparing the ground for invasion. The attack was prefaced with rhetoric: the emperor Sui Wendi (the onetime general Yang Jian) sent agents into the south with three hundred thousand copies of a manifesto listing all of the faults of the new southern emperor, and explaining that vice had deprived the southern dynasty of the Mandate of Heaven.

10

In 589, the actual war began. Sui Wendi marched towards the southern capital Nanjing; by the time his armies arrived at the city’s walls, the power of the Southern Chen had crumbled. With remarkable ease, the Sui forces took control of the city and then of the south. Sui Wendi had restored China to unity with his two-pronged strategy: first words, then swords.

Next he put into place a whole series of quick and effective reforms. He deprived everyone but the army of weapons, thus reducing the possibility of rebellion and eliminating bloody private feuds. He ordered the Great Wall, the barrier against northern invasion, to be rebuilt where it had crumbled. He reorganized the two untidy governments of the north and south into a single, rational, efficient unit, highly structured and hierarchical, each office having its own rank, its own set of privileges, and even its own particular uniform. Like Justinian to his west, he ordered that a new set of laws be drawn up that would apply across the entire empire, replacing the untidy contradictory mass of local regulations: the New Code. To reduce southern hostility to the northern takeover, he married his son and heir, Yangdi, to a southern bride. And, recognizing that the north and south would never hold together without free intercourse between them, he began to build a series of new canals from waterway to waterway that would ultimately link the Yellow and Yangtze rivers. The finished waterway became known collectively as the Grand Canal.

11