The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (40 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

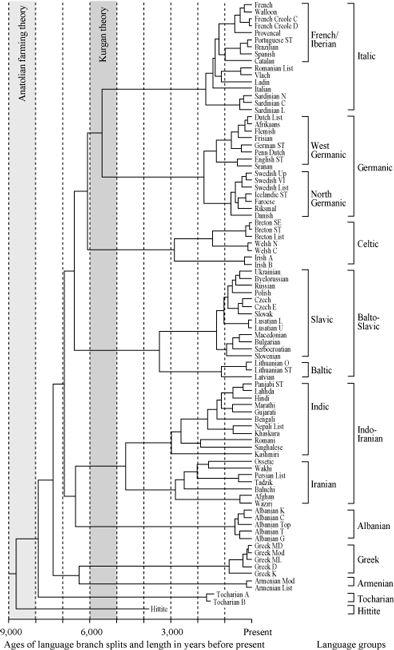

Figure 6.2a

Indo-European language tree constructed mainly from living languages, with dated branch splits and lengths (dates from 9,000 years ago to present; grey time-bars represent the relevant periods for the two alternative origin theories of Indo-European languages).

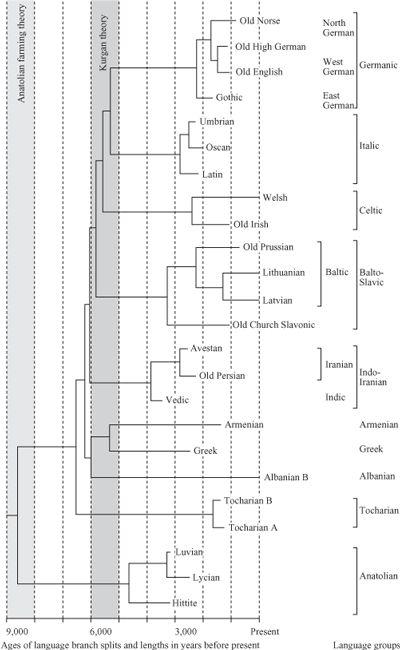

Figure 6.2b

Indo-European language tree constructed mainly from dead languages, with dated branch splits and lengths (dates from 9,000 years ago to present; grey time-bars represent the relevant periods for the two alternative origin theories of Indo-European languages).

So far, so good for Eastern Europe – what about the west? The rest of Europe divides neatly into the three remaining Indo-European branches, all splitting apart in roughly the same millennium, 6,100–5,500 years ago, the deepest being celtic, with the Germanic and Italic (Romance) branches showing a marginally closer relationship. (At least that is what these trees show; there is an alternative view that there was an Italo-celtic branch, which would have been Mediterranean.)

16

Surprisingly, this packaging seems to fit the genetic story well. It would be difficult not to suggest LBK pots carrying Y-group Ian up the Danube for Proto-Germanic languages. We could then match the spread of Cardial Ware along the Mediterranean with I1b2 and E3b for Proto-Italic, and ultimately Maritime Bell Beakers and the same Y markers for Proto-celtic spreading along the Atlantic coast into the British Isles.

But neat associations are not proof, and the Neolithic is not the only period in which such a pattern could have occurred.

Certainly the two Neolithic genetic trails to the British Isles that I have described, one north via Germany and one round the south via Spain and France, could fit the spread of both languages and farming. But, as I have shown, the first such post-Younger Dryas trails could have started during the Early Mesolithic, carrying Ingert to Germany and Rory (R1b-14) to Ireland.

The problem is that the reasons for two main routes existing from the Balkans to Britain are not specific to the Neolithic. They are the result of certain unchanging geographical features providing corridors such as the Danube, the Mediterranean and the Atlantic, and barriers such as the Alps. After all, the big opportunity for Holocene expansion north was not only the Neolithic, it may also have been the climatic amelioration at the end of the Younger Dryas, 11,500 years ago. Archaeologists and geneticists have reused an old classical word,

palimpsest

(meaning a manuscript or papyrus that has been written on and erased repeatedly), to describe this phenomenon of pattern overlaying. It applies equally to the trails derived from Cavalli-Sforza’s famous Principal Components maps (Figure 6.1).

17

If, as climatologist/archaeologist pair Jonathan Adams and Marcel Otte have suggested,

18

Indo-European could have begun to spread in the Mesolithic, then where would that leave the Indo-European farming-linguistic hypothesis? Has celtic been in Ireland for 10,000 years rather than the conventional Iron Age, 2,300 years ago, or the Bronze Age in the second millennium

BC

, or the Neolithic, 6,000 years ago? While I find the Neolithic language hypothesis most attractive for Europe and the Near East in general, this sort of confusion and the overwhelming

temptation to fit language branches to a favourite migration hypothesis make it imperative that splits in language trees have their own dating rather than that imposed by archaeologists to support their own particular theory.

Which takes me back to the dates obtained by Gray, Atkinson and their colleagues. These are systematically younger than would be expected from the actual dates for the Neolithic cultural spread as indicated by the archaeological record. They claim that their estimate of 8,700 years for the break-up of Anatolian, derived from both the Ringe and Dyen datasets, suits the origins of agriculture neatly. This is not really the case, since the Neolithic as measured by the earliest traces of grain domestication in Anatolia is rather older than that – more like 13,000 years ago.

19

However, the revolution did not happen overnight, and hunting and gathering continued among the Anatolian villagers.

20

So, it could be said that they did not become fully committed farmers until about 8,500 years ago, but this is uncomfortably close to the first Neolithic evidence in the Balkans. This creates real problems for their estimates for the break-up of Dyen’s Meso-Europeic group, with dates of 6,100 years ago for the separation of the ancestor of celtic and 5,500 years for the split between Proto-Germanic and Proto-Italic (6,000–5,000 years ago in the Ringe set) (

Figures 6.2a

and

6.2b

). These are about two thousand years too late for the archaeologically dated movements of Cardial Ware and LBK.

Gray and Atkinson comment on the younger age of these West European splits, suggesting that the western branches could be evidence for a Kurgan nomadic expansion from the Caspian Sea succeeding the Neolithic expansion. There doesn’t

seem to be any geographical sense or archaeological evidence for this rationalization. When they come to calibrating and dating the break-up of these three major Meso-European branches into their extant modern European languages, it all seems to be flat-packed into the millennium and a half since the Romans left Britain. This foreshortening of virtually the entire history of diversification of Meso-Europeic languages into less than two millennia is, to a great extent, a consequence of linguists concentrating on the limited window of written sources.

Glasgow husband-and-wife linguist-and-geneticist team April and Robert McMahon have reviewed these attempts at dating linguistic splits. They discuss a foreshortening effect, resulting from undetected word borrowing between related languages (e.g. ‘beef’ in Modern English was borrowed from Norman French rather than inherited from Old English), which could have systematically underestimated the dates of splits in this kind of analysis, even with a carefully winnowed dataset:

These effects are also minimized by Gray and Atkinson’s use of a carefully prepared dataset, based on the best available linguistic knowledge, in the shape of Dyen, Kruskal and Black (1992) – though even here, as we have shown and as Gray and Atkinson (2003) suspected, there are individual miscodings which are mainly internal to subgroups, but which could again have a foreshortening effect on individual branch lengths.

21

Peter Forster and Alfred Toth take the opposite approach to Gray, Atkinson and colleagues. Instead of trying to approximate the ideal language tree or network by studying only well-attested cognates, they initially include in their network any and all lexical changes within their chosen word list, including both

those resulting from borrowing and those ‘genetic’ changes resulting from regular intrinsic sound changes. They clean up afterwards by removing terms with too many synonyms. To analyse this soup of linguistic ‘mutations’, they then incorporate methods used for dating mtDNA branches with imperfect or ambiguous information. In their words:

a network may contain reticulations when convergence (i.e., through historical loan events and chance parallel changes, or even through data misassignments incurred by the researcher) has obscured the evolutionary tree. The linguistic network approach is therefore expressly intended to search for treelike structure in potentially ‘messy’ data.

22

Two outcomes may be predicted from such an approach. One is that, by explicitly including borrowing as a ‘language mutation’, their dates would avoid that source of foreshortening and perhaps turn out dates older than those obtained by the more conventional, exclusively cognate-based methods. The other is that, given their smaller dataset – including poorly known, dead celtic languages with many more unknowns, linguists would scream ‘Poor data!’ In the event, their dates for the fragmentation of Indo-European in Europe are very old, possibly 10,000 years ago, suggesting an Indo-European expansion in the Early Mesolithic, just after the end of the Younger Dryas freeze-up, or maybe just consistent with the leisurely onset of agriculture.

23

As for the screaming, an extensive critique of their methods and results may be found in the same recent publication ‘Why linguists don’t do dates’ by April and Robert McMahon.

24

What relevance do all these contentious considerations of language dating have for the peopling and cultures of the British Isles? Potentially, they offer a different perspective on the Germanic/celtic divide in Britain. As I have stressed, the possible relationships of language to archaeology and genetics are all speculative and can be misleading. But the genetics tells us the Welsh/English genetic border is perhaps of Neolithic or earlier antiquity, and the archaeology tells us that there were always two separate sources of cultural flow into the British Isles, with Ireland and the British Atlantic coast relating southwards, and the east coast of England relating across the North Sea. If the prehistoric language split followed the same Neolithic geographical divide, the cultural and linguistic divisions between the English and the rest could be just be as old too, or at least older than the Roman invasion. In Colin Renfrew’s picture, which has Indo-European languages spreading on the back of the Neolithic, the best candidate Indo-European branch to accompany the English Neolithic and Bronze Age would be Germanic.

Which brings us to the last of the main questions asked in this book: who are the English, and when did they arrive?

EN FROM THE NORTH:

A

NGLES

, S

AXONS

, V

IKINGS AND

N

ORMANS

HE

S

AXON

A

DVENT

[A] council was called to settle what was best and most expedient to be done, in order to repel such frequent and fatal irruptions and plunderings of the above-named nations [Picts and Scots] … Then all the councillors, together with that proud tyrant Gurthrigern [Vortigern], the British king, were so blinded, that, as a protection to their country, they sealed its doom by inviting in among them (like wolves into the sheep-fold), the fierce and impious Saxons … to repel the invasions of the northern nations … [N]othing was ever so unlucky … A multitude of whelps came forth from the lair of this barbaric lioness, in three cyuls, as they call them, that is, in three ships of war, with their sails wafted by the wind … Their mother-land, finding her first brood thus successful, sends forth a larger company of her wolfish offspring, which sailing over, join themselves to their bastard-born comrades … The barbarians being thus introduced as soldiers into the island, to encounter, as they falsely said, any dangers in defence of their hospitable entertainers,

obtain an allowance of provisions, which, for some time being plentifully bestowed, stopped their doggish mouths. Yet they complain that their monthly supplies are not furnished in sufficient abundance, and they industriously aggravate each occasion of quarrel, saying that unless more liberality is shown them, they will break the treaty and plunder the whole island. In a short time, they follow up their threats with deeds.

1