The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (35 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

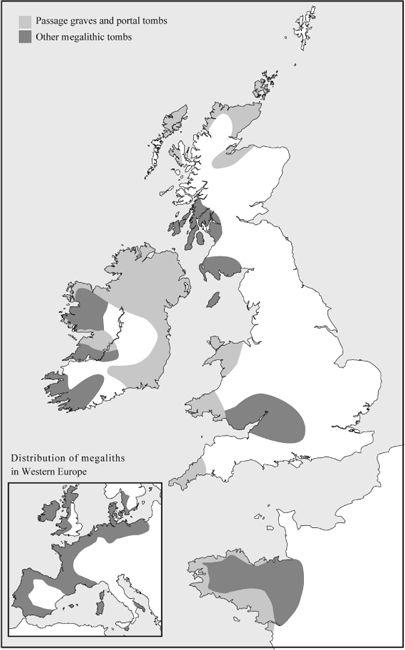

Similarly, from 5,500 years ago the inhabitants of the Orkney Islands, north-east of Scotland, began to build a variety of small, chambered cairn graves. These, although numerous, were smaller than the glorious, later Orcadian chamber tombs. Given the Scandinavian genetic links, it is worth speculating whether these early north-eastern megalithic tombs derived from the Irish– Welsh–Cornish passage grave tradition or from the Scandinavian– German–Frisian chamber graves. Orkney, Caithness and the Outer Hebrides were later to build their own more elaborate slab-lined chambered tombs. The genetic evidence I have mentioned for Neolithic male and female gene flow into this region, both from the nearby Continent and from Scandinavia, might point towards a northern Continental cultural influence.

Figure 5.9

Big stones of the Neolithic. In addition to being the southern trail of Neolithic genetic spread, the Mediterranean- and Atlantic-facing coasts of Europe and the British Isles were home to a broad band of megalithic monuments around 5,000 years ago. Northern Ireland and Orkney were the main centres of innovation in the British Isles.

Around 5,500 years ago a new type of megalithic grave, the gallery grave (with elongated slab-lined chambers), joined the Continental Atlantic scene, taking hold in Brittany and also farther east in Normandy and right up to Denmark. This date was, in Cunliffe’s words, ‘conventionally taken as the divide between the Middle Neolithic and Late Neolithic Periods – phases defined conveniently in terms of changing pottery’.

116

It also heralded the use of animals for traction and the first use of the plough in Western Europe.

117

From 5,200 years ago, wheeled vehicles appeared in Hungary; much later they were to find their way through northwest Europe to Yorkshire. But other dramatic cultural innovations were happening among the megalithic structures of Western Europe, tending to emphasize the separate eastern and western cultural inputs to the British Isles. A new ritual style took hold in Brittany and the British Isles characterized by arrangements of large standing megaliths. Their function and patterning were, at least partly, associated with the heavens. The ritual complex included stone circles, stone alignments and large stones (menhirs).

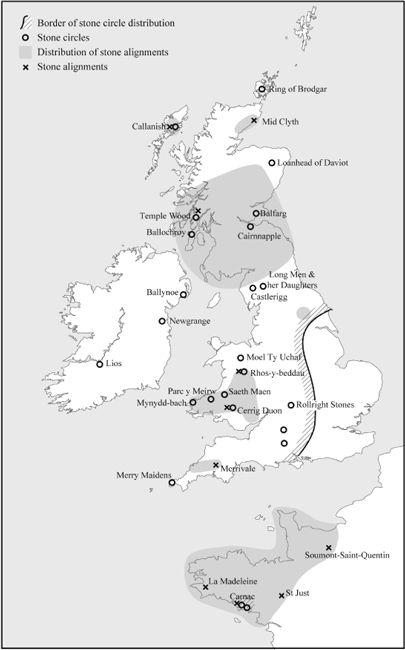

Stone circles appeared in large numbers between 5,200 and 3,500 years ago, particularly across the western half of the

British Isles (

Figure 5.10a

). Some of these were built with a clear celestial orientation. For instance, as at Stonehenge, stones were placed to align with with midsummer or midwinter sunrise. Other stones were oriented in lines. These stone alignments are found particularly in Brittany, the most famous being at Carnac, but also in Cornwall, south Wales and southern Scotland (

Figure 5.10a

). Single massive standing stones known as menhirs featured as part of this ritual complex in Cornwall and Brittany. They are also famous in the latter region as a result of the Obelix and Asterix cartoons (Plate 3). The continuity in distribution of these megalithic stone arrangements between the Pyrenees, Brittany and the western half of the British Isles would be consistent with the southern Neolithic genetic input I have described.

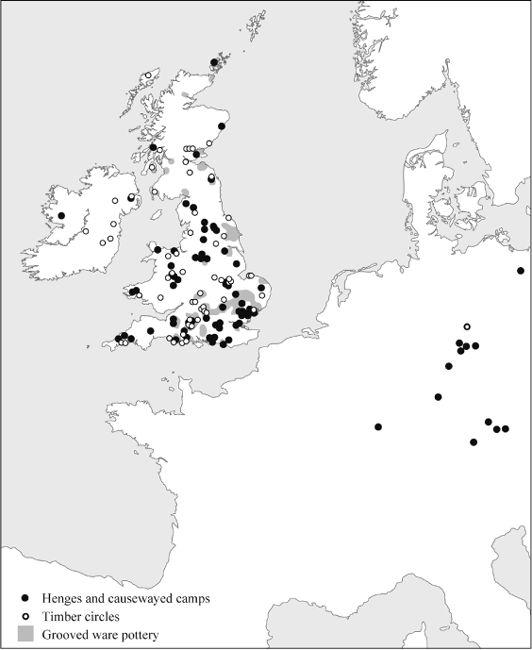

Henges, another widespread contemporary style of Neolithic monument in the British Isles (

Figure 5.10b

), had a rather more northerly representation on the Continent than the stone arrangements I have just described. Henges and timber circles may have evolved out of a more general enclosed earthwork, known as a causewayed enclosure. All these three types of enclosure are found throughout Germany and Alsace. Henges did not necessarily feature visible standing stone rings, obvious exceptions being Avebury and Stonehenge in Wessex and several in Orkney. Constructed over a long period, in general form they were large, circular, ditched enclosures. Several, such as Woodhenge and the recently exposed wooden circle on the sands of Norfolk (named ‘Seahenge’ or Holme-next-the-sea) (Plate 3) had circles made of massive tree trunks. The latter features an upturned tree in the centre of the ring with its roots exposed.

5.10a–b

Cultural influences on the British Isles from the Atlantic coast and from north-west Europe in the Neolithic.

Figure 5.10a

The Atlantic influence. The distribution of stone circles, stone alignments and menhirs in the western British Isles and Brittany.

One of the least visited Neolithic monuments in Europe is Maes Howe in Orkney. Found in association with three huge stone circles (here classified as henges), various menhirs and chamber tombs, Maes Howe is 30–40 metres in diameter. The dominating feature is a central, vaulted, corbelled chamber tomb originally 5-metres high, making it one of the finest prehistoric monuments in Europe (Plate 10).

The Orkney monuments were associated, from about 3,200 years ago, with a particular pottery, used only for ritual purposes, called grooved ware (see Plate 11 for designs very similar to those on grooved ware). Both henges and grooved ware spread rapidly as a complex ritual package, probably south, through the British Isles,

118

reaching an extraordinary concentration and development over the next six hundred years in Wessex (

Figure 5.10b

), with great henge complexes at Avebury, Marden, Durrington Walls, Knowlton, Mount Pleasant and Stonehenge. The earliest ‘Stonehenge 1’, however, was similar in design and age to the Orkney types, with a 110-metre diameter circular ditch-and-bank structure enclosing a large ring of fifty-six holes which probably held large wooden posts.

In contrast to passage graves, the spread of the cultural complex of henges, timber circles and grooved ware tended to favour the east coast of Britain as well as the south coast (

Figure 5.10b

). The distribution of grooved ware south of Scotland is exclusively in eastern and southern Britain and is not found on the Continent. As mentioned, the henge/timber circle/causewayed camp complex had a different distribution from the Atlantic passage grave zone, having its main cultural links across the North Sea in Germany, with long mounds for burial, strips of land defined by ditches or lines of pits described as cursus monuments and ditched enclosures called causewayed camps.

119

This east-side cultural picture could be suggested by the northwest European Neolithic genetic input I have described.

Figure 5.10b

From north-west Europe? The distribution of henges, timber circles, causewayed enclosures and grooved ware pottery.

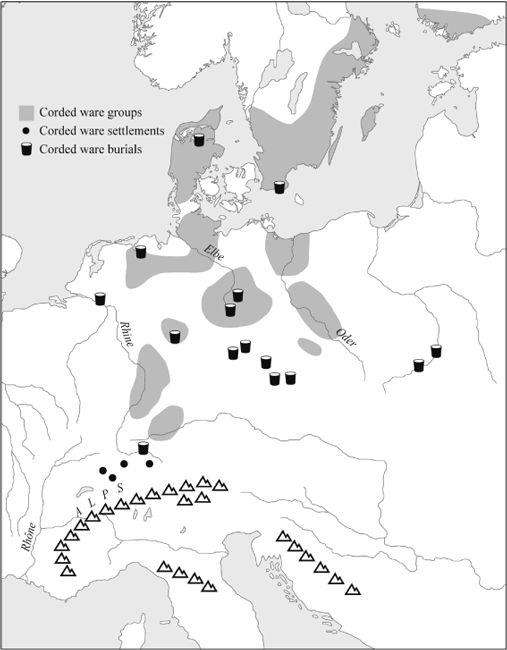

Around 5,000 years ago came another cultural ‘change’ in Denmark and the North European Plain area, which later spread extensively across Europe and also to Britain. It did not have the pomp and majesty of megaliths, but had far-reaching effects, in particular for archaeologists’ perceptions of the prehistory of the time. An important ritual change saw a move from communal to individual graves, and males began to be buried with stone axes perforated to take a haft, and distinctive one-litre drinking beakers often decorated with impressions from twisted cord. This is informatively called the

Corded Ware/Battle Axe Culture

(

Figure 5.11

).

As Cunliffe tells us, ‘The origin of the Corded Ware/Battle Axe phenomenon is a matter of continuing debate.’ And he explains why:

The use of cord decoration was well known among eastern communities extending to the steppes, while the stone battle axes were evidently copied from metal forms already well established among the copper-using communities of south-eastern Europe. In the past it was conventional to explain large-scale culture change in terms of invasions. Thus some archaeologists argued that the Corded Ware/Battle Axe ‘culture’ reflected a mass migration of warriors moving into northern Europe from the Russian steppes. Explanations of this kind are no longer in favour, and it is now generally accepted that the development is likely to have been largely indigenous, growing out of contacts between the local farming groups of the TRB (Funnel-necked Beaker) culture, the metal-using communities of the south, and pastoralists on the Pontic steppes where the domestication of the horse had taken place.

120

Figure 5.11

A cult of heroes from the East. Distribution of corded ware, battle-axe group, settlements and burials in north-west and Central Europe.

I give this quote in full to give a perspective of the prevailing archaeological attitude. While we need a good dose of caution if we are to avoid seeing invasions in prehistory where there were only spreads of fashion, Cunliffe’s phrase ‘no longer in favour’ records a change of academic fashion in itself. One reason why the ‘Kurgan’ pastoral migration from the steppes to Denmark and the Netherlands went out of archaeological fashion was that another migration was being promoted in competition during the late 1980s, and from a con siderable height of academic authority. This was of course the hypothesis of a rather earlier movement of agriculturalists with their Indo-European languages from Anatolia.

121

Significantly, at the time, neither view was supported by any physical evidence for actual movements of people.

Now that a number of genetic studies have examined evidence for the Anatolian Neolithic invasion and have found it to be present – but not overwhelmingly so – at less than 25%,

122

it would seem fair at least to see whether the Kurgan hypothesis can be falsified on the genetic evidence. Usefully in this case, the genetic evidence extends from humans to the first domesticated ponies in north-west Europe, although the genetic dates for the latter are still uncertain.

123

In my view a Late Neolithic invasion

of humans and horses from Eastern Europe (Kurgan or otherwise) cannot be falsified genetically – at least not yet.