The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (42 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

As we shall see, one possibility is that the Belgae spoke Germanic languages, perhaps ancestral to Dutch or Frisian,

which they carried to England even before the Roman invasion. Unfortunately there is little in the way of direct evidence or clear indications from Caesar or Tacitus to determine what languages were spoken in North Gaul or in the parts of southeast England occupied by the invading Belgae. While several personal and tribal names in Belgica described by Caesar have a clearly Gaulish derivation, a larger proportion do not, and some may have belonged to the Germanic branch of Indo-European.

One of the most important linguistic surveys of West European names is

Gaulish Personal Names

by David Ellis Evans, former Oxford University Professor of Celtic. Evans acknowledges that only one of the three main regional dialects of Gaul, ‘which Caesar specifies … (“Belgic, Celtic, Aquitanian”)’ may correspond to the modern celtic-language division at all, and there may have been other ancient dialects in addition.

7

He prefaces this sober qualification with the gloomy comment that he has ‘been particularly worried by one problem, namely that of identification of Celtic in Ancient Gaul, of deciding whether a particular proper name is Celtic or not’.

8

Taken out of context, these bleak statements might make one wonder if his study is of any value, so I should stress that his academic, self-effacing qualifications hide extraordinary scholarship and numerous rigorous proofs. His source material includes Caesar and other authors, and many ancient inscriptions. The evidence, particularly from ancient inscriptions, gets progressively more solid as he moves south towards the southern Roman province of Narbonensis. So, for the Belgic part of Gaul, if there was a single or main language, the message from personal names is that it cannot be assumed to have been celtic.

Caesar tells us some interesting things about the ‘Belgic’ inhabitants of northern Gaul, although not much directly about the languages they spoke. For instance, at the beginning of his

Gallic Wars

he notes:

Of these [the Gauls] the Belgae are the bravest … and they are the nearest to the Germans, who dwell beyond the Rhine, with whom they are continually waging war … The Belgae rise from the extreme frontier of Gaul, extend to the lower part of the river Rhine; and look toward the north and the rising sun.

9

Caesar goes on to say that he has heard that the Belgae are forming a confederacy against the Romans, so he goes up to northern Gaul to investigate:

As he [Caesar] arrived there unexpectedly and sooner than any one anticipated, the Remi, who are the nearest of the Belgae to [Celtic] Gaul, sent to him … ambassadors: to tell him that they surrendered themselves … to the protection and disposal of the Roman people: and that they had neither combined with the rest of the Belgae, nor entered into any confederacy … and were prepared … to obey his commands, to receive him into their towns, and to aid him with corn and other things; that all the rest of the Belgae were in arms; and that the Germans, who dwell on this [southern] side of the Rhine, had joined themselves to them; and that so great was the infatuation of them all, that they could not restrain even the Suessiones, their own brethren and kinsmen …

10

The Remi then gave Caesar the low-down on the Belgic opposition:

When Caesar inquired of them [the Remi] what states were in arms, how powerful they were, and what they could do, in war, he received the following information:

that the greater part of the Belgae were sprung, from the Germans

[my italics], and that having crossed the Rhine at an early period, they had settled there, on account of the fertility of the country, and had driven out the Gauls who inhabited those regions … The Remi said, that they had known accurately every thing respecting their number, because being united to them by neighbourhood and by alliances, they had learned what number each state had in the general council of the Belgae promised for that war.

11

The Remi told Caesar that the tribes of the Belgic confederacy included their brethren the Suessiones, and

the Bellovaci [who] were the most powerful [and] promised 60,000 picked men … the Nervii, … as many; the Atrebates 15,000; the Ambiani, 10,000; the Morini, 25,000; the Menapii, 9,000; the Caleti, 10,000; the Velocasses and the Veromandui as many; the Aduatuci 19,000; that the Condrusi, the Eburones, the Caeraesi, the Paemani, who are called by the common name of Germans [had promised], they thought, to the number of 40,000.

12

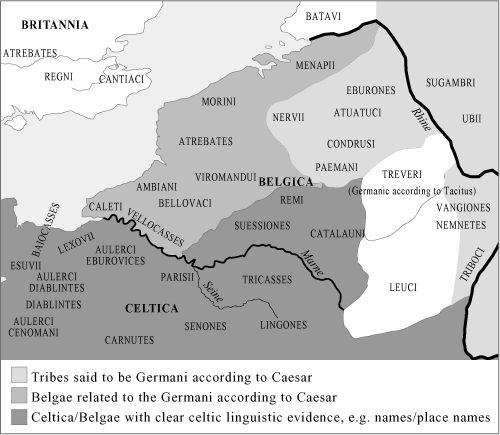

Caesar’s description here of the Belgae as largely descended from Germans seems to have been forgotten; yet he confirms it again later in his book. The last four tribes he mentions in this passage he clearly identifies as German and as occupying Belgic territory to the west of the Rhine, an area rather larger than is now included in modern Germany west of the Rhine (Westphalia and the Rhineland) (

Figures 2.1a

and

7.1a

). Caesar also later identifies those tribes occupying the part of western

Germany to the east of the Rhine (the Sugambri and Ubii), as solidly German. In other words, if we follow Caesar’s use of the term ‘Germans’, their west-Rhineland territory roughly followed the modern north-west German borders down south as far as Koblenz, where the Moselle joins the Rhine.

This whole area west of the Lower Rhine, later to be called Germania Inferior by the Romans, included modern Luxembourg, the Ardennes and eastern Belgium, where a dialect of Low German is still spoken. These present-day Germanic-language areas previously constituted the north-eastern quarter of Caesar’s Belgica. In contrast, to the south of this region, part of the lower Moselle was the former territory of the Treveri, who

do

seem to have had a couple of celtic-derived personal names and were centred around modern Triers (or Treves, after the Treveri) on the Moselle.

13

South of Koblenz, the tribes on the west of the Rhine were also ‘Belgic Germans’. Tacitus identifies a further three Belgic tribes as Germanic: ‘Such as dwell upon the bank of the Rhine, the Vangiones, the Tribocians, and the Nemnetes, are without doubt all Germans’ (see

Figure 7.1a

).

14

This block of the west upper Rhine, divided from Germania Inferior by the Treveri region, was later reclassified as part of the province of Germania Superior.

The direct evidence for German tribes in Belgica at the time Caesar was writing does not stop in the eastern part of Belgica. The Nervii, whose numerical contribution to the Belgic confederacy matched that of the Bellovaci, Caesar also later identifies as descended from the Cimbri and Teutones,

15

who invaded Belgica at a much earlier date, probably from the Danish (Cimbrian) Peninsula. These are both regarded as more likely Germanic-rather than celtic-speaking tribes, in spite of the superficial similarity between ‘Cimbric’ and ‘Cumbric’.

16

Tacitus seems to confirm this (albeit in an ambivalent way) and even extends the label to the Treveri: ‘The Treverians and Nervians aspire passionately to the reputation of being descended from the Germans’

17

(

Figure 7.1a

).

Figure 7.1a

Germanic tribes of North Gaul, according to Caesar. Caesar implies that the areas in north-east Gaul shown white on this map were Celtic.

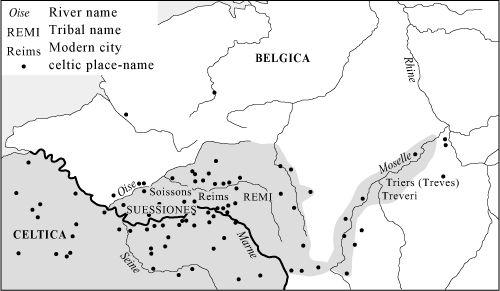

Figure 7.1b

Evidence of celticity in North Gaul from place-names. This is consistent with Caesar, making most of Belgica non-celtic, with the exceptions of the central-eastern areas occupied by the Remi, Suessiones, Treveri and Catalauni. (Place-name terms:

briga

(mountain);

kondate

(joining of rivers);

nant

(valley); Noviantum;

vern

(alder).)

As for the other confederate tribes, further west in Belgica, there are suggestions for some celtic-derived personal names. For instance, the Belgic tribe the Atrebates had a twinned tribe in southern England with the same name, which means ‘settlers’ in celtic. However, the Atrebatean that Caesar made their leader, Commius, had a name which cannot be securely derived from celtic roots.

18

Commius would later become a thorn in Caesar’s side when he turned-coat and led Gauls against Caesar in the famous battle of Alesia. It seems that he was the same ‘Commios’ who then moved to Britain, as yet unconquered, to become leader of the Atrebates there (

Figure 2.3

) and started a dynasty, even stamping his own name on minted coinage (see p. 330).

As for the rest of the Belgic tribes, although they have a few personal names with a celtic derivation, such names belong mostly to only three tribes: the Treveri, the Remi and their ‘brethren’ the Suessiones. Given Ellis Evans’ ambivalence over the celtic nature of languages spoken by the Belgae, it is worth looking at other evidence.

A common last resort to get a handle on what languages people spoke in such unknown situations is to analyse ancient and surviving place-names linguistically. Place-names can preserve

the identity of older languages as bits or even whole words even after those languages have otherwise been completely replaced. River-names are even more resistant to change and can tell of older linguistic affiliations. This persistence, however, can make it impossible to tell when such names were

given

. Furthermore, there are often doubts about the strength of the language attribution, or whether the derived language represents that of the bearer or informant. For instance, the eminent Celticist Patrick Sims-Williams of the University of Aberystwyth points out that ‘Many Seans and Kevins do not speak Irish, while many Ryans and Kellys speak Welsh.’

19

He adds that ‘Some care is needed in interpreting the presence or absence of such names, since place- and ethnic names can be taken over from foreigners, while foreign personal names can be adopted for reasons of prestige.’

20

Even tribal labels such as ‘Belgae’ and ‘Atrebates’, found in Latin texts referring both to northern Gaul and to south-east Britain, can have celtic derivation without necessarily defining the language they spoke (see above).

Given that these cautionary words can cut either way, it is worth looking carefully at a study of place-names in the former Belgica by German linguist Hans Kuhn, entitled (in translation) ‘The People between the Celts and the Germans’, in which he finds only a very limited and specific distribution of shared celtic names to the north-east of Paris (

Figure 7.1b

).

21

He uses eight different Celtic name-roots to map the former area of celtic-linguistic influence. Although Kuhn has other linguistic agenda, the presence of these names in Celtic Gaul, their geographical congruence on his map, and their absence from most of Belgica tends to provide support for their relevance in this discussion. These celtic place-name roots are found

only in two small regions of southern Belgica, where they are associated with particular river systems. Nearest to Paris, we see a cluster of celtic names bounded by four tributaries of the Seine, going from west to east: the rivers Oise, Aisne, Ourcq and Marne. This area of celtic name-clusters coincides with the territories of the Celtic Remi and of their recalcitrant Celtic brethren the Suessiones, as can be seen from Caesar’s description and, of course, confirmed by the modern city names Reims and Soissons. The other, much more limited cluster is found further north-east, on the River Moselle, and is associated with the territory of the Celtic Treveri and Treves, the modern city of Triers (

Figures 7.1a

and

7.1b

).

22