The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (43 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

This localized ‘celtic’ place-name evidence in the Reims, Soissons and Triers regions is much more abundant than any found in south-east England (see below). Kuhn’s analysis is consistent with the impression given by Caesar’s description of Belgica: that only a small minority of the peoples there were actually celtic-speaking, and that these comprised mainly the inland Treviri, Remi and Suessiones, with the territories of the Suessiones spreading directly into Celtica.

From Kuhn’s map we can also see that the rest of Belgica, in particular the maritime regions, were devoid of celtic place-names. While the cluster of preserved celtic place-names spreads south of the Marne and the Seine into Celtica, it notably does not spread west of the Oise towards the Belgic coast (i.e. towards those parts nearest England, including Calais on the French side), where the emigrants to England were supposed to have come from. These ‘non-celtic-place-named’ areas were the same coastal territories occupied by Belgic hostile confederates such as the Caleti, the Bellovaci (near Beauvais), the Atrebates,

the Ambiani (near Amiens), the Morini (near St-Omer), and the Menapii and Nervii (both in Belgium) (

Figure 7.1a

).

So what was the language spoken in the part of the rest of Belgica that wasn’t actually occupied, in Caesar’s words, by ‘Germans’? Early Germanic place-name roots are found throughout a large part of northern Belgica south of the Rhine.

23

Kuhn is more concerned with a narrow 150 km wide strip north of the Seine, for the place-names of which neither celtic nor Germanic derivations are possible, only ‘pre-Germanic’. This area is what he calls ‘The People between the Celts and the Germans’. The language imported by the Belgae and mentioned by Caesar and Tacitus could have belonged to either Kuhn’s ‘early Germanic’ or ‘pre-Germanic’ group, without necessarily being identical to that spoken by the tribes the Romans called the Germani.

Any language locally imported into Britain by the Belgae before Caesar’s first landing in 55

BC

had an odds-on chance of being non-celtic, and about an evens chance of having a Germanic origin. So, we need to look more closely at the evidence on the spot in south-east England. Unfortunately, use of Latin as the military and elite language tends to obliterate the linguistic evidence from inscriptions in Roman England, and neither confirms a universally celtic-speaking Ancient England, nor reveals any clear trace of a Germanic import in personal or place-names, except perhaps from Germanic-speaking legionaries imported by the Romans.

The study of place-names in Roman Britain started with George Buchanan in the sixteenth century, and over the last two

centuries has grown into a minor industry supporting several professorial chairs in the British Isles. Three standard works bring together much of the best scholarship invested in this subject in the last fifty years:

Language and History in Early Britain

by Kenneth Jackson of Edinburgh University,

Gaulish Personal Names

by David Ellis Evans and

The Place-names of Roman Britain

by Leo Rivet and Colin Smith. A magnificent new work of erudition by Patrick Sims-Williams published just after I delivered my manuscript draws all this celtic scholarship together in a comparative analysis and composite map covering all Europe and Anatolia (summarized in

Figure 2.1b

).

24

It is clear from these works that there were celtic-derived place-names and personal names in England during Roman times.

While there is no doubting the quality of place-name evidence for the presence of the celtic language family in Roman England, there are questions of how much was celtic and specifically where, which require systematic comparison with other regions of the British Isles subjected to the same scholarly analysis. The main questions one should ask of such place-name surveys are how much celtic was

spoken

in Roman England, and which dialects and what other languages were spoken at the same time, or had been in the past. This might seem like setting impossible goals, but opinions vary so much among linguists, some saying that nearly everyone in Roman England spoke Latin, and others that nearly every indigenous inhabitant primarily spoke celtic.

It is because of this controversy that these questions need to be asked, if only to gauge the strength of evidence as to whether English replaced celtic or Latin, or whether some Germanic language was already present in eastern Britain and later evolved into Old English. Old English inherited less than a couple of

dozen celtic words, and those were mainly from celtic-speaking areas such as Cornwall and Cumbria, whereas the Latin bequest was more like two hundred.

25

In comparison with the huge French component brought into English by the Normans, even the early Latin borrowings are few and the celtic borrowings notable for their near absence. Where one language rapidly replaces another (i.e. ‘language shift’), the lexicon of the previous language is usually more severely affected than the structure. But to me, the lack of Latin and complete absence of celtic borrowing in Old English points to one of two extremes. One is the traditional wipeout theory; the other is the possibility that there was a Germanic language already being spoken in the areas invaded by Anglo-Saxons, which more naturally hybridized with ‘Anglo-Saxon’.

Geography

for celtic place-name frequency

Is it possible to make valid quantitative comparisons between the classical place-names of Roman England and contemporary ones in other European regions with celtic-speaking populations? It is, and there is one way of doing it – by using a comprehensive place-name survey performed throughout Europe by the same survey team during ancient times. The Greek geographer-astronomer Claudius Ptolemaeus (Ptolemy), who lived in the Egyptian city of Alexandria in the second century

AD

, carried out just such a survey during the later part of the Roman occupation of Britain. His

Geographia

, in seven volumes, became the standard text on the subject until the fifteenth century. Two chapters in volume 2 deal with the British Isles.

Chapter 1

,

‘Hibernia island of Britannia’, is concerned with Ireland and the smaller isles;

Chapter 2

, ‘Albion island of Britannia’, covers mainland Britain (England, Wales and Scotland). Ptolemy used a comprehensible grid reference system analogous to longitude and latitude, and gave lists of the prominent coastal landmarks, rivers and estuaries, as well as the names of the British tribes and main towns. While the ancient names given by Ptolemy in his map are far fewer than place-names gleaned by celticists from scouring modern maps or the classical texts, they have the two great advantages that the process of survey he used was consistent throughout Europe and it was contemporary with the Roman occupation of Britain.

A publication based on an international workshop organized and edited by Patrick Sims-Williams of the University of Aberystwyth and David Parsons of the University of Nottingham has laid out Ptolemy’s place-names region by region with standardized linguistic derivations.

26

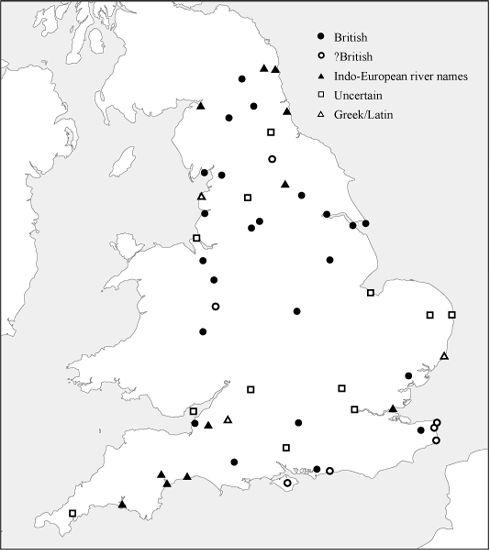

Parsons wrote the chapter on England, and moves through the data systematically, explaining his exclusions and inclusions. Ptolemy mentioned 88 names relating to England in his chapter on Britain. Of these 37 were place-names, 18 names of rivers, 16 of tribes and a further 17 of coastal features. After removing 7 duplications and the 16 tribal names, Parsons is left with 65. Of those, 13 (20%) are Greek or Latin and 22 (34%) are clearly British celtic; a further 14 (22%) are ‘very difficult’, 8 (12%) ‘uncertainly’ British celtic and another 8 (12%) ‘?Pre-Celtic Indo-European’.

27

So, only a third of Ptolemy’s English place-names are British, and the concept that there could have been other Indo-European languages in Roman England is supported. Now, while Parsons is relieved that a third of Ptolemy’s place-names from England

are celtic-derived, he acknowledges the large gap that needs explaining:

It is gratifying that the names explicable as Celtic make up the largest single class, since there is a generally held assumption that the language of all the population of present-day England is likely to have been British [i.e. Brythonic-celtic speaking] at the time of the Roman conquest. It is striking, however, that nearly half of the names are nonetheless more or less opaque, at least to the modern scholar. There are doubtless various reasons for this. The scarcity of records of British [i.e. Brythonic celtic] other than names, together with the language’s early disappearance from most of the area, are problems only partially compensated for by the survival of Welsh, Breton and Cornish …

28

In other words, Parsons is concerned that other lexical evidence for Brythonic celtic being spoken in England is virtually absent, and its universal use in pre-Roman England rests almost solely on celtic names which constitute only one-third of Ptolemy’s list. The situation for place-names in southern England is even worse: when celtic names north of the Humber and the Mersey, in the West Country and in the Welsh borders are removed from Ptolemy’s map, only six definite celtic names are left in the south (

Figure 7.2

). This distribution of celtic place-names in England is the opposite of what should be expected on the basis of population density. Southern England, then as now, carries a much larger population than either Wales or most of northern England, with their high country and moorland.

Comparing this quantitative analysis of Ptolemy with Patrick Sims-Williams’ new map, which looks at all sources of ancient place-names, shows that it is the south and east coasts which have the lower rates of celtic place-names, with the highest rates being north of the Thames around St Albans in the ancient territories of the celtic tribe, the Catuvellauni (

Figure 2.1b

).

Figure 7.2

Analysis of place-names in Ptolemy’s second-century

AD

map of England shows a comparatively low rate with celtic (British) attribution in southern England. There are only six definitely British (i.e. celtic) names in the south, excluding the West Country.

Perhaps the greatest concern with place-name evidence is that it cannot be dated, even when a particular language is identified. This fact is acknowledged by Parsons immediately after the summary quoted above: ‘Above all, however, I would want to stress the lack of chronological depth in place-name evidence.’

29

This brings us to what Parsons calls ‘records of British other than names’, which essentially means coins and inscriptions in the British Isles before and after the Roman occupation.

Linguists, historians and archaeologists often use place-names to reconstruct the past movements of languages and peoples, but the ages of such labels are notoriously elusive. Place-names are liable to outlive the language that created them. This fact can be used both ways in dating arguments. Archaeologists are now good at dating material culture, but artefacts (pots, tools, jewels, weapons, etc.), their most abundant form of evidence, are usually silent on language. One kind of artefact can, however, give us useful direct clues about language in the past. That is the written word, inscribed on stones, ornaments and coinage, and transcribed from original texts.

As we have seen, the distribution and diversity of Continental celtic languages towards the south of Europe can be clarified archaeologically from inscriptions in Etruscan, Latin and other scripts, some going back to the sixth century

BC

. Arguments against this inference – that the southern distribution of inscriptions merely reflected these alphabets’ spread from the south – cannot explain why Continental celtic inscriptions continued to remain restricted to the south of Europe even after the spread of the Roman Empire and writing.

Can we use this approach to determine and date the presence, absence and spread of insular celtic in the British Isles before and after the Roman occupation? Well we can, but only up to a point. That point is determined by the spread of writing, but also by who actually commissioned the inscriptions. Roman script seems to have been the first to enter the British Isles, but it did so long before the Roman occupation, and even at the time of Caesar’s sortie in 56

BC

it was present in the form of coins struck with the names of local chieftains which are most prevalent in southern England, along the Thames Valley. The earliest of these coins were struck by rulers of the first century

BC

, such as Tincomarus of the Atrebates region and Commios, who may have been the same ‘Commius’ who rebelled against Caesar in the Gallic War. The problem with this sort of information is that the text on the coinage was limited and mainly in the form of names, which does not add much to personal name study from ordinary written texts.