The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (18 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

To some extent, this conservatism is predictable if one considers the founding events. As I mentioned earlier, the impact of a new movement of genes into an old population depends on the size of the pre-existing gene pool. So, the first colonization of a virgin area will tend to expand and fill up the habitable space, and the initial mix will have a greater effect on the make-up of the final population than subsequent immigrations. The Saami in Lapland, for instance still show clear signs of the very small size of their original founding female population a few thousand years ago, in that up to 52% of their population has the relatively infrequent V type of mtDNA (see below).

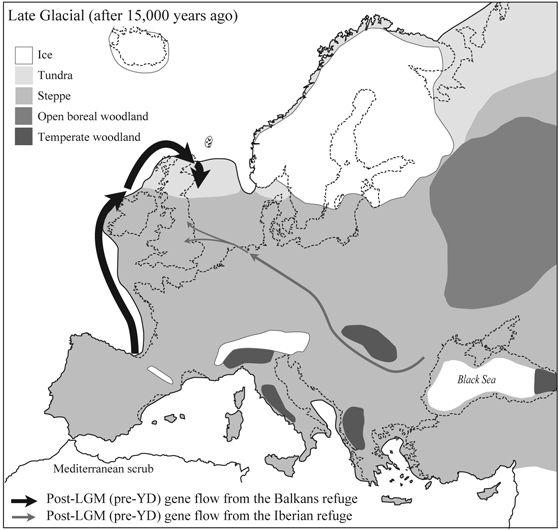

There is general agreement and good evidence that Western Europe was largely recolonized from the south-western refuges in southern France and Spain, which were separated from the more easterly refuges by the French Alps and some more. But before we look at the primary genetic sources for the repeopling of the British Isles, I would like to describe an important genetic and cultural cross-fertilization which has only recently been brought to light and which took place from east to west in Europe in the last few millennia before the LGM.

Between 26,000 and 22,000 years ago, in the millennia leading up to the LGM, two new Stone Age cultures started to replace the famous, so-called

Gravettian

styles of the Middle Upper Palaeolithic in the south of France and in Spain. In this early glacial period, one of these cultures predominated; it is now called the

Solutrean

, after the village of Solutré in eastern France. Characteristically, Solutrean stone-knappers produced finely crafted flint spear and arrow points, which were worked on both faces using fine invasive flaking. They also made ornamental beads and bone pins as well as creating evocative prehistoric art.

During the build-up to the LGM, the Solutrean initially flourished on both sides of the Pyrenees, especially in Aquitaine in south-west France, but for the period after the worst cold snap of the LGM, 22,000 years ago, evidence for the Solutrean culture tends to contract south of the Pyrenees to the main western Ice Age refuge, which was northern Spain.

21

Coincident with this chilly retreat, a new technical style became dominant in the Dordogne refuge cultures in the south-west of France. This is known as the

Magdalenian

, after the type site at La Madeleine.

The Magdalenian culture, later to define human re-expansion throughout Western Europe after the Ice Age, was previously assumed to have arisen locally from the Solutrean in south-west France. However, a reappraisal of the earliest Magdalenian in France suggests that it arose from the pre-glacial, so-called Epi-Gravettian cold-adapted culture in Eastern Europe and spread south-west to France shortly before the LGM.

22

This new insight has, confusingly, given rise to yet another culture name, after a place in the Dordogne, the

Badegoulian

. With this new trans-alpine insight, the Badegoulian culture can be seen to have been continuous in Europe between 25,000 and 13,000 years ago; it came to the fore in south-west France with the retreat of the Solutrean 23,000 years ago, and then thrived throughout the LGM.

The point of this digression, apart from underlining humans’ extraordinary cultural capacity for adapting to extreme adversity, is that we can suggest both female and male gene-line markers to accompany this pre-glacial east–west cultural cross-fertilization.

23

Before the LGM, two maternal gene groups dominated Europe: U and HV. The earliest of all was U (nicknamed Europa in

Out of Eden

), arriving from around 50,000 years ago and 30,000 years before the LGM. She still makes up a background of around 9% of modern European maternal lines. HV arrived in a second wave, 10,000 years before the LGM.

24

In

Out of Eden

I described the origin of the HV group, the ultimate root of the majority of European female lines. She was born, possibly in the Trans-Caucasus, over 30,000 years ago and may have been a genetic signal running in parallel to the early Gravettian cultural spread. Early on, HV split into two branches: the smaller one known to mitochondrial geneticists as Pre-V, and the much larger branch H, both of which subsequently spread all

over Europe. I shall use as a nickname for this large group the Russian name

Helina

, and the widespread Latin name

Vera

for Pre-V’s daughter group, V. (Vera is the generic Latin name for ‘truth’, and V gave us the first clear genetic evidence for the Basque glacial refuge; I could not find a Basque name beginning with V.) Pre-V, perhaps 26,000 years old, is found infrequently in a limited distribution stretching from east to west, from the Trans-Caucasus through the north Balkans and Central Europe to southern Spain and Morocco.

25

The female ambassadors from east of the French Alps, who could be genetic proxies or parallels for the pre-glacial Badegoulian trans-alpine culture spread, are these very two: H and Pre-V. Helina is now the most common female group in Europe, accounting for around half of gene lines in the West, including the British Isles, but this rise in matriarchal prominence and rank took place just after the LGM. The evidence for the trail of these younger female marker lines is rather good.

Being numerically far greater, the female Helina group ought to be a better marker for the first recolonization events than its close relative Vera. However, for a long time the hope of a clear picture of Helina’s movements was not fulfilled, partly because of her pan-European distribution but mainly because there appeared to be insufficient geographical pattern in the Helina subgroups.

26

Now, with the increased resolution (i.e. accuracy and number of branches) of the Helina family tree resulting from extended analysis in key parts of the mitochondrial genome, it has become possible to trace at least eight specific Helina subgroups expanding in Europe after the LGM.

The geographical picture for Vera, with her smaller numbers and more limited distribution, had already emerged, in 1998,

27

so I shall present the data for Vera first.

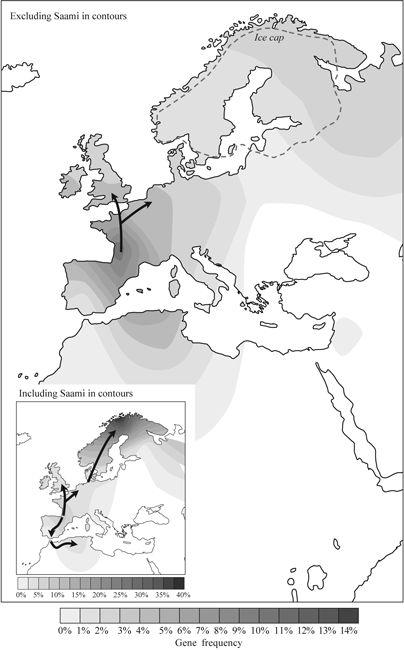

The Vera group, Pre-V’s genetic daughter, tells us rather clearly about the next stage. Today in Europe, Vera is found most frequently in western and northern regions, suggesting that she was one of those gene groups who expanded out of the south-western refuge. She almost certainly began her life in one of the southern refuges, in either south-west France or Spain, and has been in Western Europe now for 16,300 years.

28

Soon after the LGM she spread out from the refuge, heading north and west along the Atlantic coast (much later forming a large component of the Saami ancestors), but also south to Morocco and east to Central Europe. Scandinavia and Lapland have the highest Vera rates, but because of the presence of a large residual ice sheet they were not colonized until the last 10,000 years (discussed in detail in

Chapter 4

).

29

After the Saami and Basque, in Western Europe Vera is found at highest frequency in south-west France (over 10%) and at a progressively declining frequency up the Atlantic coast (

Figure 3.4

). Most of northern France and the British Isles achieve around 5% Vera, for instance. So, if we look at the continental shelf, including the British Isles but excluding Scandinavia, it can be seen that Vera’s frequency falls off north of the 53rd parallel and both north and east of the Rhine.

30

This distribution may well reflect the distribution of the ice sheet and environmental conditions 16,000 years ago, just after the end of the LGM, and the limit of the initial human spread (

Figures 3.1

and

3.3

).

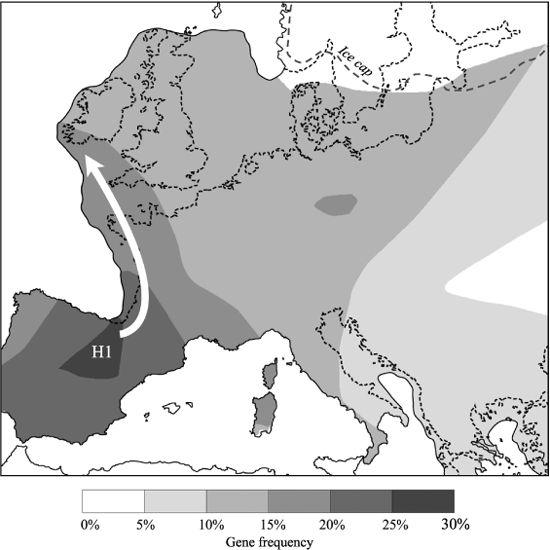

At least a dozen specific subgroups of the Helina group have dispersed in Europe since the LGM. One of them – H1 – seems, like her aunt Vera, to have originated in the west Iberian refuge (the Basque Country) and expanded early into north-west Europe after the LGM. She now accounts for 66% of Helina lines in Spain and 45% of Helina in the rest of north-west Europe (overall, including the British Isles).

31

Smaller subgroups, H2, H3, H4 and H5a, may have had a similar history in the Iberian refuge, but expanding during the Mesolithic, and account for a further 16.5% of Helina in the United Kingdom, bringing the proportion of

identified

subgroups of the Helina contingent there to over 60% of British Helina types. Clearly it might eventually be possible to trace and date more British Helina subgroups back to Iberia, but on these figures the specific early expansions of Helina and Vera from the south-western Ice Age refuge before the first farmers account collectively for around 60% of all modern Helina and Vera groups in the British Isles.

Figure 3.3

Colonizing ‘Greater Britain’ after the Ice: a summary map of early recolonizing gene flow into northern Europe and the British Isles 15,000–13,000 years ago. The bulk came from the Iberian refuge, which contributed perhaps a third of maternal ancestors for the British Isles during this cool period. The reason for this apparently high gene flow is only partly that they were founders; the other reason is that most of northern Europe was grassland and rich in big game.

Figure 3.4

Ancestor Vera, who gave the first clear genetic evidence of Ice Age refuges and early re-expansion from Iberia into the north-west. Contour map of Vera gene frequency – arrows indicate direction of gene flow based on the gene tree and geography. The lower (inset) image shows a Mesolithic founding event in Lapland – which is removed from the analysis in the main figure to avoid distortion and because it happened after the Scandinavian ice cap melted. Vera is a smaller group than Helina, but is more specific to the colonization of Western Europe from the Iberian refuge.

Figure 3.5

The immediate impact of maternal re-expansions into north-west Europe from Iberia after the Ice Age from 15,000 years ago. Contour map of H1 (Helina main sub-group) gene frequency – arrows indicate direction of gene flow based on the gene tree and geography. Contours follow greater land area resulting from low sea level and avoid the ice cap (Scandinavia excluded from analysis).

Of course, this is not the whole picture since we are looking only at specific dated Helina and Vera subgroups, and not at other, less well-resolved subgroups or other gene groups apart from Helina and Vera. These two gene groups as a whole contribute about 42% of the total extant British gene pool, so the specific individual earlier subgroups H1 to H5 and Vera would together account for only around a

quarter

of today’s maternal lines. However, since most of Helina expanded in Europe during the Late Upper Palaeolithic anyway, 42% may not be a gross overestimate for this period (

Figure 3.5

).

32