The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (44 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

As mentioned in

Chapter 2

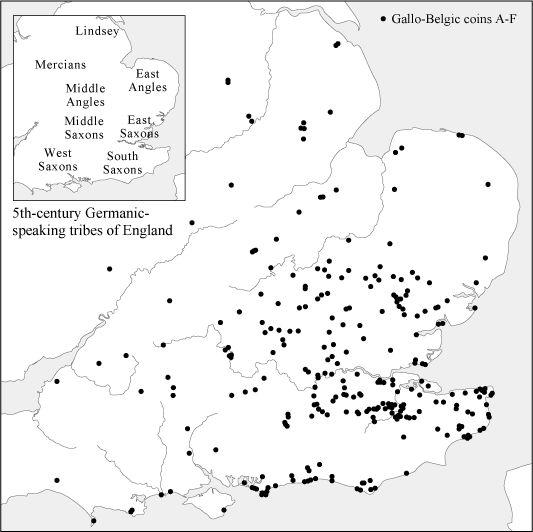

, perhaps the most interesting aspect of early British coins is not where they were made but where they were

not

made. The latter areas are those for which there is the most evidence for celtic-language use and in the form of inscriptions on stone, and include southern Britain, Wales, Cornwall and the West Country. So the distribution of early coins in Roman and pre-Roman Britain is almost an exact negative image of the distribution of post-Roman celtic inscriptions (

Figure 2.2

).

Apart from the general point that the main influences on early coinage in Britain came from Belgic rather than Caesar’s ‘celtic-speaking Gaul’, there is a more specific clue to how close, culturally and politically, the people of southern England

were to the Belgae. The clue lies in the British distribution of Gallo-Belgic coins dating to the period of Caesar’s all-out war against the Belgae.

Gallo-Belgic coins are found in Britain in more or less the same areas as were affected by the early ‘Saxon invasions’ (before c.

AD

500). Notable concentrations occur in Kent, along the Sussex Coast and either side of the Thames. The density of Gallo-Belgic coin finds falls off sharply in areas occupied by Angles in the fifth century

AD

, in Norfolk, Suffolk and north of the Ouse. Gaps in the south-east include a band north of the Sussex coast stretching westwards from the Weald Forest (

Figure 7.3a

).

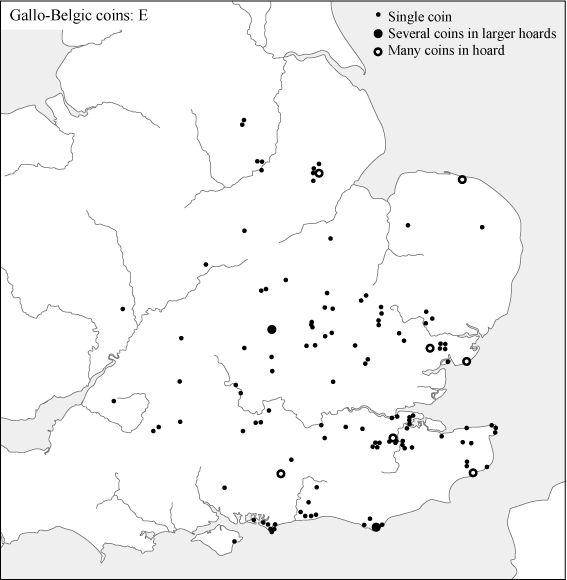

Gallo-Belgic coins found in Britain are divided into six classes, denoted by the letters A–F. Archaeologists generally agree that, with the exception of class B and probably A, which arrived earlier, there was a significant influx of Gallo-Belgic coinage around the time of Caesar’s all-out war on the Belgae. Specifically, Gallo-Belgic E (and probably C) coins of the Ambiani may have flooded in during the years 56–55

BC

prior to Caesar’s attack on North Gaul in order to help pay for the Belgic insurgency.

30

Cunliffe suggested that if all Gallo-Belgic coins except B arrived during the Gallic War, ‘the gross distribution of the Gallo-Belgic coinage should reflect in general terms the extent of the territory over which the war had its effects’.

31

The geographical distribution of the time-focused Gallo-Belgic E coins (and, to a lesser extent, of C coins) is nonetheless broad and matches the overall British distribution of Gallo-Belgic coinage during the Roman period (

Figure 7.3b

). This suggests to me that the relationship between Belgic Gaul and what was later mainly Saxon England was more than just between treaty allies, and more as Caesar suggested – one of cultural continuity and common concern. If both the Belgae and the British south-east were celtic-speaking, that closeness might be expected, but if the Belgae were

not

celtic-speaking or, as Caesar suggests, were largely descended from Germans, then it would make less sense – unless some tribes of south-eastern England also spoke Germanic languages.

Figure 7.3a

Gallo-Belgic coin distribution in Britain (all types, A–F). This distribution thus excludes Wales, the West Country, Cornwall and the North, and is coincident with the territories occupied in the fifth century by ‘Saxons’ and, to a lesser extent, Angles (inset).

Another conclusion may be drawn from the wealth of indigenous name-stamped coins throughout the Roman occupation of England, namely that powerful Britons in England were able to make strong statements about their local status and identity in Roman script, but without feeling the necessity to Romanize their names or any other written content. This implies they were not so Romanized that they had lost their own sense of cultural identity. One should therefore not interpret the near-total absence of celtic inscriptions of any other kind in England during and after the Roman occupation, as evidence that Britons had lost their indigenous languages.

Figure 7.3b

Map of Gallo-Belgic type E coins, which appeared in southern England in 55

BC

in payment for English support against Caesar’s Belgic campaign.

Curiously, the strongest evidence for the presence of celtic language among the middle classes in England is almost anecdotal and comes from a comic metallic source in the West Country, at the edge of the area where coins are found:

In the second to fourth centuries the metal curse-tablets from Roman Bath tell a … story. Typically, they were deposited by angry people who had lost their clothes while bathing because they were too poor to pay a slave to guard them. On them, we find a tremendous number of British Celtic names [and text]: about 80, compared to 70 Roman names.

32

As far as the text content is concerned, as opposed to just celtic names, all stone inscriptions in south-east Britain during the Roman period are in Latin; significantly,

none

are written in the celtic vernacular. The names are mostly Latin as well, in stark contrast to the names on coins. Patrick Sims-Williams has some interesting observations on this phenomenon and points out that the language of names varies with the medium on which they are recorded. On stone inscriptions in Roman Britain, he says:

we tend to see monotonous Latin names … Celtic-looking names are few and far between, especially those distinctively Celtic compound names of the sort which Julius Caesar encountered in Britain (

Cassi-vellaunus

,

Cingeto-rix

, and so on). The number of such compound names in Romano-British stone inscriptions is almost the lowest in the Latin-speaking Empire …

33

The last sentence in this statement seems to raise doubts about the strength of the celtic influence in England. Alternatively,

Sims-Williams explains that the dominance of Latin in stone inscriptions may reflect a bias towards the military, since we do find celtic names in signatures of artisans such as potters, tile-makers and metal-smiths.

34

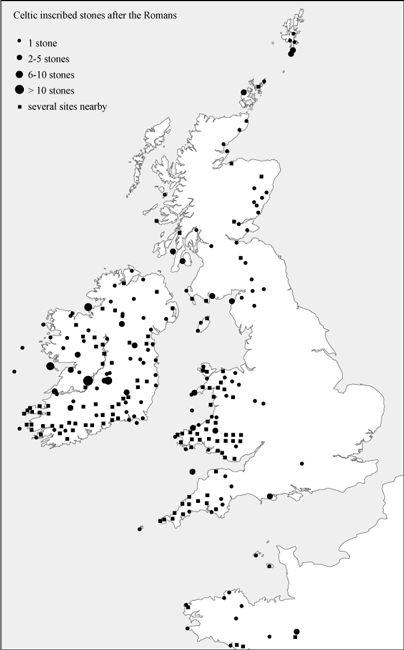

When the Romans withdrew from Britain, something very strange happened in south-east England: virtually no inscribed stones were set up at all, either in the immediate post-Roman period or afterwards. One stone with an Ogham (an Irish script imported into Britain during this period) celtic inscription at Silchester is likely from the late Roman period; one in Wareham is in Roman script, probably celtic, from the sixth or seventh century. The relative difference in numbers of inscriptions could be the relative paucity of good stone in the south-east, unlike the West Country, but this would hardly produce the near-complete void in England (

Figure 7.4

). By the time inscriptions started up again, much later, they were in Anglo-Saxon or Medieval Latin, not celtic.

This sudden down-tools might have been a consequence of soldiers leaving, since the inscribed stones are argued by some to have been set up by the Roman military. However, many of the inscriptions are civil. Even if the military explanation applies, it is not as simple as that, because inscribed stones continued to be set up in previously Roman-occupied parts of Wales, Cornwall, Cumbria and Scotland,

35

for at least the next seven hundred years, and

their

Roman soldiers had presumably left too. Furthermore, taking Wales as representative of these regions of celtic post-Roman Britain, these inscriptions initially included Latin names, but over the next couple of centuries a diversity of celtic names came overwhelmingly to predominate, with Latin names either disappearing or becoming celticized.

36

Figure 7.4

Distribution of over 1,200 celtic inscriptions on stone in the British Isles and Brittany (

AD

400–1100). During the Roman period, all inscriptions in south-east Britain were in Latin, none in celtic. By the time they started up again in England after the Roman exit, they were in Medieval Latin or Anglo-Saxon. This leaves a near-total absence of celtic inscriptions in England and also large parts of Scotland, at any time.

But there is clearly a problem of logic here. If there are plenty of Latin

and

celtic inscriptions from after the Roman collapse in all

other

Romanized regions of the British Isles, why are there no post-Roman inscriptions, Latin or celtic, to speak of in England until the first runic (i.e. non-celtic) stones, which appear later? Surely the Anglo-Saxon invasions were not a complete and instantaneous blitzkrieg. Even the most avid supporters of the Anglo-Saxon wipeout theory accept that it could have been possible only over several hundred years. If celtic languages were spoken universally in England throughout the Roman occupation, surely they would have initially persisted, as in Cornwall and Wales, for several hundred years before succumbing to Anglo-Saxon?

This seemed such an extraordinary ‘English’ anomaly to me that I searched the literature for explanations. Not surprisingly, ancient stone inscriptions are an intensively researched area, and British scholarship has much to say on it.

37

There is a very accessible web site set up by the Department of History and the Institute of Archaeology of University College London, which has recently completed a major project to catalogue celtic inscriptions on stone in the British Isles and Brittany, known as the Celtic Inscribed Stones Project, or CISP.

38

This project catalogues over 1,200 celtic inscriptions made between the years

AD

400 and 1100 in the celtic-speaking regions of the Early Middle Ages: Scotland, Ireland, Wales,

Brittany, the Isle of Man and parts of western England. Included are all stone monuments inscribed with text, whether in the celtic vernacular or in Latin, in the Roman alphabet or Ogham. Excluded are runic inscriptions, which are Germanic and appear in England only after a brief brief hiatus in the early fifth century (see

Chapter 9

). As can be seen from the map drawn up by this project (

Figure 7.4

), with the exception of the West Country, the lowland and most densely populated areas of England are notable for the absence of celtic inscriptions.

Not only do we see a void of celtic inscriptions in England, but there is also an almost total absence of any relict lexical evidence for celtic languages in Old or Modern English. The same applies to the bulk of regional dialects from most parts of England, except in Cornwall and Cumbria. One would normally expect to find some incorporated remnants of a language that has been replaced, a so-called linguistic substratum. There are, however, only four attested celtic words to be found in English (or perhaps a couple of dozen if local dialect terms are included, such as

tor

and

pen

, both meaning ‘hill’, and

crag

).

39

These numbers do not add up to a significant lexical substratum although linguists have noted structural celtic influence.

40

In other words, this lack of evidence is not consistent with celtic language having a major role in the evolution of English.