The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (38 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

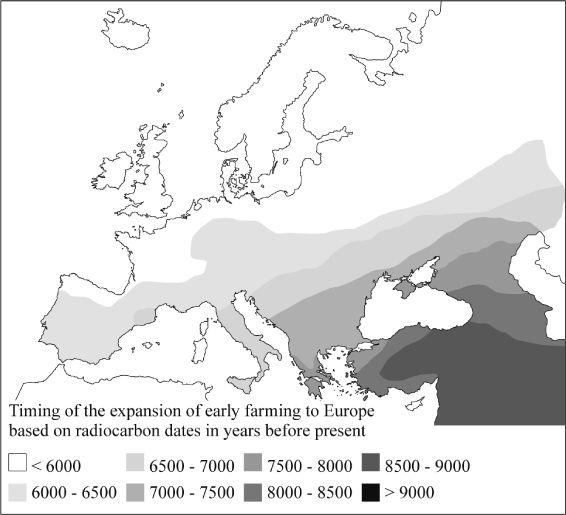

Figure 5.15a

Contour map of Norwegian gene flow into Shetland, Orkney, and northern and western Britain during the Bronze Age (composite of I1a-6a and R1a1–3a).

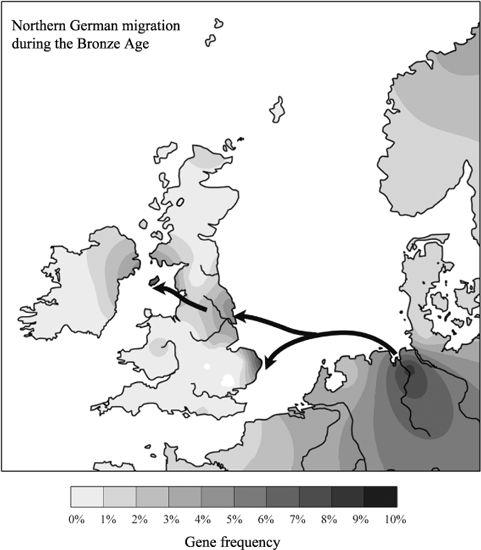

Figure 5.15b

Contour map of gene flow into eastern England from northern Germany during the Bronze Age (composite of I1a-7a and R1a1–3c; arrows indicate direction of gene flow based on gene tree and geography).

It is worth speculating on a possible Bronze Age equine genetic link between Shetland, Britain and southern Scandinavia. German-based geneticist Thomas Jansen and colleagues from Cambridge University analysed mitochondrial DNA in domesticated horses both ancient and modern. Their work revealed two particular gene groups strongly associated with North European ponies. One of these groups, C1, identifies North European pony breeds on both sides of the North Sea (Exmoor, Fjord, Icelandic, Connemara and Scottish Highland) and is restricted to the Balkans, the British Isles and Scandinavia, including Iceland. The other group, E, consists entirely of Icelandic, Shetland and Fjord ponies.

149

The devil is again in the dates, because the mtDNA mutation rate has not been fully established for horses, but the link across the North Sea is definitely older than the historical Viking raids.

150

However, the ponies were unlikely to have been imported by the Vikings. Ponies were used in Pictish times (about

AD

550–800) in eastern and northern Scotland, and are shown on carved stones. They presumably passed on some of their genes, including the C1 maternal type, to today’s Scottish Highland pony. Shetland ponies (related maternally to Scottish Highlands though their modern-day appearance is very different) have been around for over 2,000 years. If one adds to this the fact that ponies were present in Scotland by at least 2,700 years ago, it is certainly difficult to credit genetically related pony imports to the Vikings, and more likely that they arrived earlier with other Scandinavian visitors.

Before leaving the prehistoric cultural landscape, I should like briefly to mention the Early Iron Age, without repeating all the La Tène/Hallstatt discussion of

Chapter 1

. Study of the British parallels to the La Tène cultural package of the Central European Iron Age has not revealed any archaeological support for large-scale Iron Age migrations into the British Isles. If we take Ireland as a ‘Celtic’ example, La Tène artefacts are relatively rare, and were almost always locally made.

151

It is becoming difficult to find archaeologists and historians who still accept the idea of a Celtic migration to Ireland.

152

There is, in any case, no genetic evidence for an Iron Age migration from my analysis. Even if my dates for very small-scale Bronze Age human gene flow between north-west Europe/Scandinavia and Britain were overestimates, the specific lines I have identified do not reach the Atlantic fringes of Britain, let alone Ireland.

The big question remains: what language group was used by traders on each side of the North Sea and both north of the Channel and along the south coast of England during the Neolithic and Bronze Ages?

HO SPREAD

I

NDO

-E

UROPEAN LANGUAGES?

The documentary evidence on prehistoric British languages is fragmentary, relying as it does on a few indirect remarks by Caesar and Tacitus, and can be of little help in telling us which came from where, and when. Our Germanic, celtic and other languages are unique cultural repositories and have some potential of their own to reveal past cultural movements. Indeed, moves to preserve celtic languages as a cultural identifier on the Atlantic coast should not be dismissed lightly as nationalism. Language is more important for cultural identity than most genes, except perhaps for those mutant genes found in Northern Eurasia, which interfere with the normally dark skin pigmentation of humans.

1

Nearly all languages spoken in the British Isles are Indo-European in origin, and it is of great interest to know

when they each arrived. It is not possible to fulfil the dreams of migrationist archaeologists and match skin tones with genes, but it is of interest to everyone to be able to compare culture and descent. In other words, Indo-European languages have their own unique relevance for the peopling of the British Isles.

The secret fascination of the Indo-European language family for prehistorians is that there are very few extant languages in Europe that belong to other families. The exceptions are famous in that they break the rule. Apart from some European members of the Uralic family (Hungarian, Finnish, Estonian and Saami), Basque is the most widely touted exception since it has no known relatives at all and has a special pride of place for geneticists. The Basque Country is not only one of the central locations of the West European Ice Age refuge, but there are clear genetic and cultural differences between Basques and the surrounding populations. As I have mentioned, these differences have been overstated – the Basques are a genetically representative population for south-west Europe who were conserved and isolated and largely bypassed during the Neolithic. Some linguists even detect substratum evidence of Basque in structural aspects of English and insular celtic languages. However, in Roman times they were not the only linguistic exception: Iberian was another, totally different, non-Indo-European language.

Archaeologists have long sought to link the spread of Indo-European languages with one or other of the east–west cultural sweeps across the Continent detected in the archaeological

record of the last 10,000 or so years. As with all such cross-disciplinary matching games, the problem is in the dates. Historical linguists tend towards a generally sceptical view, given the current lack of agreement on language dates and wide confidence margins on existing ones. Until there is robust dating of the Indo-European language family, their initial expansion could as well have been earlier in the Mesolithic or even Late Upper Palaeolithic as, in the more popular theories, in the Neolithic or the Bronze Age.

2

In my previous books, I have promoted the view that prehistoric population expansions were, in general, more likely to have resulted from climate change than any killer cultural advantages possessed by invaders, for instance farming, with mass-migration and population replacement. Europe is no exception to this generalization,

3

as I hope I have shown so far in this book. The expansion of a language family signals mainly cultural spread rather than population migration. Although both necessarily have to be involved to some degree, it is vital to separate rather than conflate the two processes. Conventional archaeology is essentially a record of culture. Genetics addresses migration, however imperfectly. Language, being in between, needs to be treated on its own, ideally with its own internal dates.

Although it is interesting to make comparisons, language history should not lightly, or forcibly, be ‘fitted up’ to any other proxy for human prehistory such as the archaeological record, physical anthropology or genetics. The stories that each of these proxies tell may be similar, but more often than not they are different. I take a more cautious view in this than American biological writer Jared Diamond, who argues that, with exceptions, ‘The simplest form of the basic hypothesis –

that prehistoric agriculture dispersed hand-in-hand with human genes and languages – is that farmers and their culture replace neighbouring hunter-gatherers and the latter’s culture.’

4

In the past, archaeologists have tended to stress the migrational implications of language reconstruction. For part of the last century, warlike, battleaxe-wielding, horse-riding Kurgan nomads riding out of southern Russia in the Late Copper/Early Bronze Age were the favoured ‘Aryan’ harbingers of Indo-European languages.

5

Later, it became fashionable to invoke farmers arriving from the Near East, bringing their own languages, to compete with Meso lithic folk.

6

Enthusiasts have recruited several genetic patterns to underwrite both migrationist views.

Some of the best-known examples of these genetic patterns arose from the work of the grand seigneur of genetic studies, Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza. His group used a well-known technique,

Principal Components Analysis

, to reduce the analysis of frequency of numerous common ‘classical genetic markers’, such as blood groups in populations round the world, into a few simple measures. In spite of its grand title, this method combines complex data into an easy-to-view visual format. For instance, it splits up the variance in frequencies of numerous genetic markers between populations into a series of parcels – the components – of decreasing statistical importance, labelled ‘First Principal Component’, ‘Second Principal Component’, and so on. In effect, each component gives a composite measure of gene frequency, which can be plotted on a map (

Figures 6.1b

–

6.1d

) like the temperature in a weather forecast or like the gene-frequency maps in this book. The first and second components are generally the most important.

Each of these components assigns numerical values to each population and thus gives its own independent measure of the genetic distance between populations being studied. So, for instance, one might expect Turks to be more distant genetically from the English than they are from Greeks, which is indeed what we find when we look at the value of their Principal Components. It would not help to go further into the details and quirks of the method here; suffice it to say that the first three components may be regarded as giving,

by analogy

, the genetic equivalent of a latitude, a longitude and an altitude for genetic distance between populations.

The

First Principal Component

of variation in European populations in Cavalli-Sforza’s analysis gives a gradient of increasing genetic distance starting around Iraq, moving through Turkey and north-west towards Scandinavia (

Figure 6.1b

). This just happens to fit the postulated north-westward spread of farmers into Europe from the Near East (

Figure 6.1a

). The

Third Principal Component

alternatively just happens to fit a similar pattern radiating out from southern Russia, which could fit the Kurgan invasion hypothesis (

Figure 6.1c

).

7

These patterns all sound very neat, but there are problems with their interpretation and the message carries no date-mark, as we shall see.

In his influential book

Archaeology and Language

, first published in 1987, Colin Renfrew eloquently and lucidly trashed the Kurgan hypothesis along with other theories based on horses, skull shape, Beaker people and cord-impressed pottery, using a number of arguments, not the least of which was an authoritative injunction against using unfashionable concepts of migrationism. Yet a form of migrationism called ‘wave of advance’ was and still is at the heart of Renfrew’s own preferred model for the spread of Indo-European languages. Although he does not insist on population replacement, he champions the view that Indo-European languages were carried by farming people ultimately from Anatolia in Turkey and spread into Europe carried by agriculture and the inexorable advance of the Neolithic.

8