The Parthenon Enigma (36 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

But radically reimagining the central image of the Parthenon’s east frieze allows the puzzle pieces to fall into place. Assuming a scene of preparations for virgin sacrifice makes the averted gazes of the flanking figures perfectly comprehensible: not only is it improper for gods

to watch mortals die, but it would defile their divinity. In Euripides’s

Alkestis

,

Apollo must leave before Alkestis dies, “lest pollution taint me in this house.” So, too, in Euripides’s

Hippolytos

,

Artemis makes it clear that she must not watch the

death of Theseus’s son: “Farewell: it is not lawful for me to gaze upon the dead, nor to trouble my eye with the dying gasps of mortals, and now I see that you are near the end.”

120

Aelian, writing in the second or third century

A.D.

, gives an account of a comic poet’s dream. In it, the nine

Muses must leave the poet’s house just before his demise.

121

On what occasions do gods assemble in the manner of the Parthenon’s east frieze? In the

Iliad

we find them convening atop

Mount Ida to watch mortals in the

Trojan War combat below. The gods cheer their favorites. In Greek architectural sculpture such “

councils of the gods” always appear on the

east

end of temples and regularly for the purpose of watching battles. The

Siphnian Treasury at Delphi, a building dated sometime before 525

B.C.

, shows the first continuous sculptured

Ionic frieze in Greek architecture. On its east side, we find the gods seated on stools, one after another, just as on the Parthenon frieze, suggesting a clear influence (below).

122

On the Siphnian Treasury, it is the Trojan War that commands the collective Olympian attention, a particular clash between

Achilles and

Memnon over the body of

Antilochos.

123

Gods supporting the Trojan Memnon—

Ares,

Aphrodite (or

Eos?), Artemis, and Apollo—sit at the left; those in Achilles’s corner at right:

a missing figure (probably

Poseidon), followed by

Athena,

Hera, and

Thetis. Between these two groups, we find

Zeus enthroned.

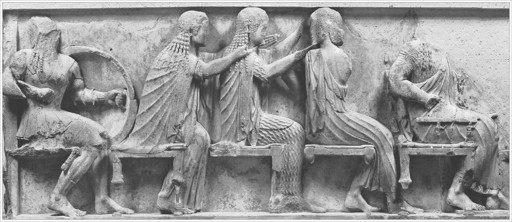

Ares, Aphrodite (or Eos?), Artemis, Apollo, and Zeus, east frieze, Siphnian Treasury, Delphi. (illustration credit

ill.65

)

A council of the gods also appears on the east frieze of the temple called Theseion (and/or Hephaisteion) in the Athenian Agora. Construction of this temple was begun sometime between 460 and 449

B.C.

, though it was not finished or dedicated until much later, around 416.

124

The sculptured friezes on its east and west porches were probably carved in the 430s or 420s, after the completion of the Parthenon. At the center of the east frieze, just above the porch, we see a battle that has been variously identified as Greeks versus Trojans, Theseus battling Pallas and his sons, and gods versus Giants.

125

Judith Barringer has offered an attractive suggestion, identifying the scene as representing the war between early Athenians and the people of Atlantis, a clash from the antediluvian past, famously referenced in Plato’s

Timaeus

.

126

Six divinities sit in attendance, three to either side of the central combat. The identities of those at right are uncertain: Poseidon or

Hephaistos (?),

Amphitrite (?), and one illegible figure. To the left we see Athena, Hera, and Zeus, seated on rocky outcrops.

Barringer laments the fact that there are no iconographic parallels for an Atlantis-versus-Athens showdown, but this would seem perfectly in keeping with the site specificity of such a temple sculpture. The

iconography of the Parthenon’s east frieze, like the

east pediment of Zeus’s temple at Olympia, is also unexampled in contemporary sculpture or vase painting. And this is precisely what has led to the great enigma concerning its subject. Our best guide in such temple mysteries is the ultimately

genealogical function of architectural sculpture; it demands the telling of local versions of myths, grounding the formula in specific landscapes, cult places, family lines, and divine patronage. And so iconography, far from hewing to a general repertoire throughout the Greek world, can be as maddeningly variable and contradictory as myth itself.

A third frieze featuring an assembly of gods stands just meters away from the Parthenon. The little

temple of Athena Nike was built at the very western edge of the Acropolis in the 420s

B.C.

and finished during the teens of the century (

this page

).

127

Its east frieze shows a lineup of divinities whose identities are debated. Nonetheless, some of them have been named, from left to right:

Peitho,

Eros, Aphrodite, and, farther along,

Leto, Apollo, Artemis,

Dionysos, Amphitrite, and Poseidon, with a fully armed Athena, standing at the center of the composition. The god shown

just to her right is probably

Hephaistos. Next, we see

Zeus, enthroned, and then

Hera,

Herakles,

Hermes, Kore,

Demeter, the

Graces, and

Hygieia.

128

The gods are gathered here to watch the battles that rage around the other three sides of the Nike temple. Greeks fighting Greeks appear on the north and west, and Greeks fighting

horsemen in eastern costume are seen at the south. This south frieze has been the focus of particular debate concerning just who this eastern enemy might be. One understanding sees them as Trojans. Another, advanced by

Chrysoula Kardara, holds that all three sides of the temple show Erechtheus’s war with

Eumolpos, the soldiers in eastern costume being the Thracian mercenaries who fought on the side of Poseidon’s son.

129

Still other scholars have argued that the frieze shows scenes from the

Persian Wars, with Greeks fighting the troops of Darius at Marathon or the army of Xerxes at Plataia.

130

This interpretation obviously suggests images of historical

battles rather than mythological ones. If true, it would place the south frieze of the Nike temple well outside the conventions for Greek temple decoration with its traditionally mythological subject matter. Some would counter this objection, however, saying that by the end of the fifth century the

Battle of Marathon had taken on mythical proportions of its own as a “modern legend” and was thus fair game for memorializing in architectural sculpture.

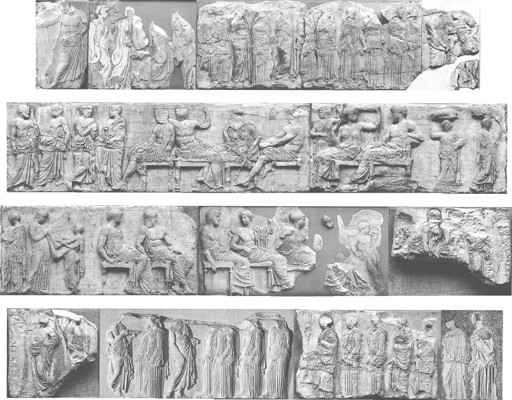

East frieze, Parthenon, showing groups of maidens, men, gods, and the family of Erechtheus. (illustration credit

ill.66

)

These patterns give one good reason to conclude that the gods on the east frieze of the Parthenon have gathered to watch a mythical battle, that of Erechtheus and Eumolpos, which has finished. They now sit as a group ready to receive the

thanksgiving sacrifice through which tensions will be

ritually resolved (previous page and front of book). The gods have properly turned their backs on the scene of preparation for the virgin’s

death (the

sphagion

, or preliminary sacrifice), looking out toward the procession that approaches from the other three sides of the temple. This procession brings animal offerings for the post-battle, thanksgiving sacrifice that follows the Athenian victory. The Parthenon frieze can thus be understood to show not just some historical Panathenaia but the very first Panathenaia, the foundational sacrifice upon which Acropolis ritual was based ever after. The offerings of cattle and sheep, of honey and water, as shown on the north and south friezes, are all made in honor of the king and his daughters as described in Euripides’s

Erechtheus

.

131

The cavalcade of horsemen is the king’s returning army, back from the war just in time to join the procession celebrating their victory.

132

The mythical

human sacrifice offered before battle is, thus, separated by the divine assembly from the thanksgiving sacrifice offered after the battle, the immortals filling the interval between that which is just before and that which is just after. The plenitude of early Athenian society is represented by the groups of elders, maidens, horsemen, and youths marching east toward the central spectacle. On account of its selflessness, the royal family is shown deified, taking their rightful places at center among the gods. Indeed

Cicero tells us that Erechtheus and his daughters were worshipped as divinities at Athens.

133

The placing of the royal family within the midst of the

Olympian gods is wholly in keeping with the temporal conceit of the frieze, which “reconciles” the time just before and just after the battle.

To either side of the divine company, we find two groups of cloaked men: six at the south and four at the north (previous page and facing page). Some are bearded, some clean shaven, several are shown leaning upon sticks. Like much else, the identity of these men is debated, along with their numbers and what their numbers signify.

134

Four additional men can be seen at the north, and one man at the very south corner of the east frieze.

135

These are traditionally identified as parade marshals, those

charged with keeping order in the procession. Two of these “marshals” have been further classified as

teletarches

, that is, officials in charge of the ceremony.

136

Group of men, east frieze, Parthenon. (illustration credit

ill.67

)

Group of maidens, east frieze, Parthenon. (illustration credit

ill.68

)

When these cloaked men to either side of the gods are counted as ten, they are identified as the Eponymous Heroes, brave individuals from the mythical past whose names were assigned to the ten tribes of Athens when the Kleisthenic democracy reorganized them in 508

B.C.

137

When counted as nine, they are seen as the archons of Athens, the tenth conscripted to the center of the “peplos scene.”

138

For this to work, one of the men on the east frieze must be subtracted and identified as a parade marshal. One scholar who counts the men as nine sees them, instead, as the

athlothetai

, a group of officials who administered religious and athletic matters for the Panathenaia. This reading gives nine

athlothetai

standing to either side of the gods with a tenth official seen in the mature male figure at the center of the east frieze.

139

The men have also been identified as lesser Athenian deities and, more simply, as generic citizens.

140

The counting and naming of the men on the east frieze is a dizzying and highly subjective enterprise. From the so-called marshals, heads can be added or subtracted to achieve a particularly significant number of heroes or officials.