The Parthenon Enigma (33 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

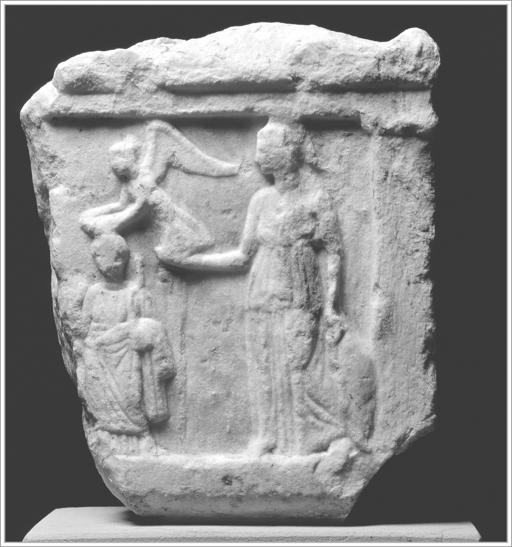

The woman shown at the very center of the east frieze has long been identified as a fifth-century

priestess of Athena Polias, a cult title meaning “Athena of the City.”

63

Strikingly, though, she lacks the chief iconographic indicator of her sacred office: the temple key. From the Archaic period on, large, rodlike keys served to identify priestesses. These women appear in terra-cotta and stone statuary, on grave markers, and in vase painting,

their rank at the top of the temple hierarchy always recognizable by the keys they hold.

64

We need only look to the image of Athena’s priestess on a fourth-century

B.C.

honorary relief found on the Acropolis to see the prominence of the temple key cradled in her left arm (previous page).

65

Raising her right hand in a gesture of

prayer, the priestess stands beside the statue of Athena Parthenos.

Nike (Victory), perched on Athena’s hand, leans over to crown the priestess with honors. We would expect a historical priestess on the Parthenon frieze to look much like this woman on the honorary relief set up on the Acropolis in the late classical period.

Honorary relief, Athena with Victory crowning priestess at lower left, found on the Athenian Acropolis. Second half of fourth century B.C. (illustration credit

ill.53

)

The absence of a key in the hand of the woman at the center of the east frieze is, in fact, the catalyst for this entire revisionary study of the Parthenon. For it was in writing

Portrait of a Priestess: Women and Ritual in Ancient Greece

that I first had to account for this so-called keyless “priestess.” Ultimately, I had to reject the conventional reading of this scene and open myself to a wider range of possibilities as to whom this female figure represents.

The Parthenon Enigma

is a direct result of this conundrum.

And so, on that August afternoon at Bryn Mawr, the full kaleidoscope of possibilities converged to focus upon a singular realization. The woman shown at the center of the east frieze has as yet no need of a key, for she is none other than the first mythical priestess of Athena, Praxithea herself. In fact, the queen is shown here just before the sacrifice of her daughter, before the goddess proclaimed her a priestess. She lacks the temple key because there was not yet a temple on the Acropolis to be locked or unlocked. Praxithea is, indeed, the Ur-priestess of Athena Polias, and her vibrant story provides the founding myth upon which the historical priesthood would be based.

The bearded man shown behind her has traditionally been identified as the priest of

Poseidon-Erechtheus or, alternatively, as the chief magistrate of Athens, the archon basileus.

66

But there is no evidence for the participation of either man in the culminating rite of the Panathenaia, a feast that was ministered by female cult officials.

67

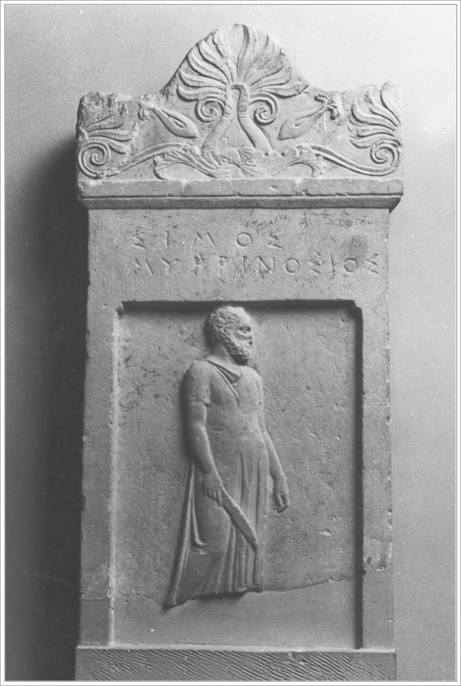

What is distinctive about this man is his costume. He wears the long, unbelted, short-sleeved tunic typically worn by priests, indeed by men who offer sacrifice. Attic

funeral reliefs that commemorate priests show them dressed in this same costume.

68

A priest named Simos (facing page) wears it on a marble gravestone of fourth-century

B.C.

date. Like the man in the center of the Parthenon’s east frieze, Simos strikes a

contrapposto

pose, with weight shifted onto his right leg. In his right hand, he holds the knife of sacrifice, the standard attribute for male priesthood and counterpart to the temple key of female sacred office. The knife identifies Simos as the one who slits the throat of the sacrificial animal.

69

Late classical Attic funerary relief of priest named Simos. Late fifth/early fourth century, Athens. (illustration credit

ill.54

)

That the male figure in the center of the east frieze carries no knife argues against his identification as a historical priest of the fifth century

B.C.

But what man would be standing with Queen Praxithea and her daughters? The mythical king Erechtheus is dressed as a

sacrificer as he solemnly prepares to offer his youngest daughter, in accordance with the Delphic oracle. The priesthood of

Poseidon-Erechtheus will be established in his

memory, just as the priesthood of Athena Polias will remember his wife, Praxithea.

The identity and sex of the child shown at the far right of the scene (following page) are vigorously debated. Is this a girl or is it a boy? The eighteenth-century commentators Stuart and Revett saw the figure as a girl.

70

During the nineteenth century and most of the twentieth, interpreters

tended to see a boy. In 1975,

Martin Robertson, Lincoln Professor of Classical Archaeology and Art at Oxford, reinvigorated the debate, arguing afresh that we have a little girl here. He pointed to the horizontal creases encircling the child’s neck as distinctively feminine, indeed as the signs of female beauty sometimes referred to as “

Venus rings.”

71

John Boardman, Robertson’s successor to the Lincoln Professorship, followed in identifying the child as a girl. Employing comparative anatomy of masculine and feminine posteriors, he contrasted the configuration of a boy’s bare bottom (

this page

), shown on the north frieze, with that of the child shown at the center of the east frieze, concluding that the two children must be of different sexes.

72

Today, the field stands evenly divided between those who see a boy and those who see a girl in this figure.

73

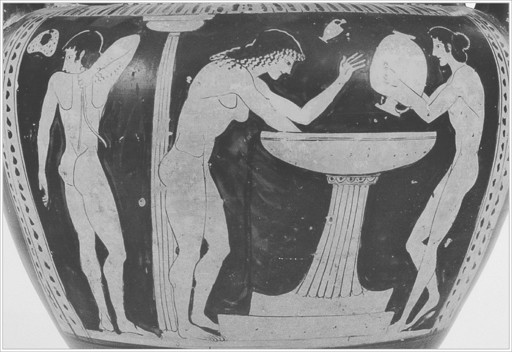

I would argue that it matters little whether this figure

looks

to the modern eye like a girl or a boy. Archaic and classical Greek artists were so unused to depicting the female nude that when confronted with this challenge, they relied on what they knew best: the male nude. A fine example can be seen on a red-figure vase in Bari, Italy, showing nude girls exercising (facing page).

74

They are endowed with well-developed masculine physiques, heavy musculature approaching that of bodybuilders. The girls’ breasts emerge implausibly from their armpits, as if afterthoughts.

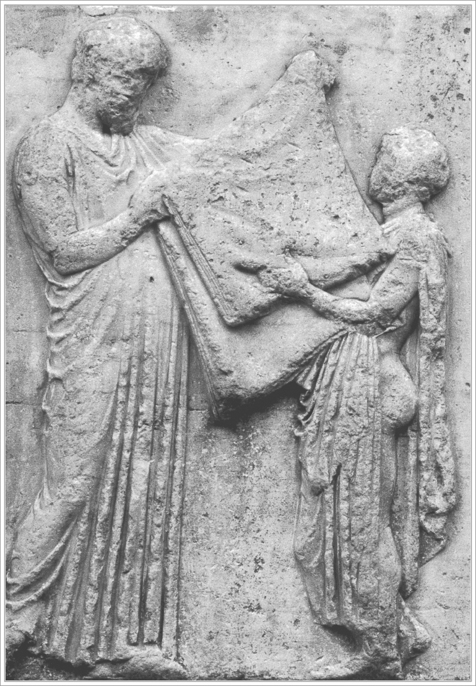

Erechtheus and daughter displaying her funerary dress, east frieze, Parthenon. (illustration credit

ill.55

)

Women exercising in palaistra. Krater, from Rutigliano. Bari, Museo Civico, Italy. (illustration credit

ill.56

)

Anatomical analysis will not provide the answer as to the child’s sex. For this we must depend on context. Those who see a boy must construct an unattested scenario in which a temple boy participated in the culminating

ritual of the Panathenaia.

75

Within the context of Greek

religion, which regularly required that female attendants serve the cults of female divinities, especially in the case of virgin goddesses, it would be very surprising to find a boy involved so prominently in the sacred rite of Athena.

76

What of the cloth? Athena’s peplos was, from the very start, women’s work. Wool from which to weave it was washed and carded by virgin hands. The little fingers of prepubescent girls, known as

arrephoroi

, set its warp under the supervision of Athena’s priestess. A team of noblewomen known as

ergastinai

, or “worker-weavers,” labored at their looms to produce the dress over a nine-month period that corresponded to the gestation term of a baby.

77

It is unlikely that such care would be taken with the sacred garment only for it then to be “manhandled” by a priest and a boy. Indeed, within the context of Greek ritual, male hands might even have been perceived as contaminating, entirely unsuited to

touching the goddess’s dress. Surely it was the priestess who presented the peplos to Athena, just as in the

Iliad

the Trojan priestess Theano offers Athena a beautifully woven fabric in supplication.

78

Those who view the child as a girl usually identify her as one of the historical

arrephoroi

, a pair of seven- to eleven-year-old girls selected from prominent citizen families to serve on the Acropolis for a festival cycle.

79

Their cult title signals that they carry “unnamed” or “secret” things, the

arreta

. The girls participated in a special nighttime ceremony, the

Arrephoria, in which they transported the “unnamable things” down the slopes of the Acropolis.

80

Later, they carried something else back up again. The girls also served at the festival of the

Chalkeia, during which they helped with the warping and weaving of the peplos. But, as we’ve said, the

arrephoroi

are always mentioned as acting in pairs, sometimes two pairs together, probably representing the outgoing and the incoming teams of two. That the child shown at the far right of the central panel has no partner makes it unlikely that she represents an

arrephoros

.

81

When viewed with reference to the foundation myth, however, this child may be identified as the youngest daughter of King Erechtheus and Queen Praxithea. She is about to be sacrificed at the hand of her father, who is dressed as a priest for the event.

Apollodoros tells us that Erechtheus sacrificed his youngest daughter first.

82

The girl’s dress is, very conspicuously, opened at the side, revealing her nude buttocks. It would be unthinkable for a historical girl, an

arrephoros

from an elite family, to be portrayed with backside casually exposed during the most sacred moment of the Panathenaic ritual.

83