The Parthenon Enigma (32 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

To be fair, some scholars have argued for a mythological interpretation, but no known myth could be adduced that adequately fit the images. Already fifty years ago, Chrysoula Kardara read the central panel of the east frieze as a representation of the inauguration or first Panathenaic festival, an overall approach that makes very good sense, though she did not have the benefit of the surviving text of Euripides’s

Erechtheus

.

53

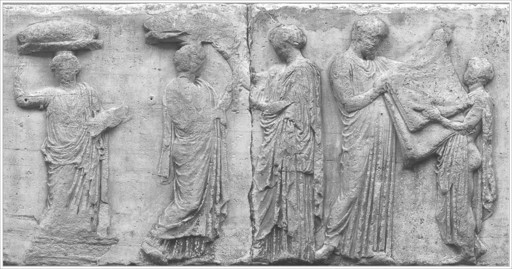

Kardara identified the figures in the central panel (above and

this page

) as King Kekrops and the child Erechtheus/Erichthonios handing over the new peplos to Athena. She saw the female figures at left of the scene as Mother Earth (Ge) with two of Kekrops’s daughters. Kristian Jeppesen, who likewise wrote before the

Erechtheus

fragments were found, identified the adult male figure at the center of the scene as Boutes, brother of Erechtheus, standing with the child Erichthonios. He saw the female figures at the left as the three daughters of Kekrops: Herse, Aglauros, and Pandrosos.

54

Some interpreters reject any and all notions of a unified narrative subject for the frieze, seeing it as a series of images with multiple meanings. Still others, unwilling to see the frieze as a snapshot of reality but unable to find a myth to fit, view it as a vague reference to a timeless, generic Panathenaia.

55

Erechtheus and family flanked by Hera and Zeus (at left), Athena and Hephaistos (at right), east frieze, Parthenon. (illustration credit

ill.50

)

Burkhard Fehr sees no link whatsoever between the Parthenon frieze and the

Panathenaia.

56

Instead, he reads the frieze as a comprehensive discourse on Athenian democracy, illustrating the correct behavior of members of the community within this democratic system. For Fehr, the central panel of the east frieze presents an exemplum of the ideal family unit. We are looking at the Greek

oikos

(household) in which a mother trains her daughters in textile production while the father presents his young son with a

himation

(mantle), the ultimate symbol of citizen status.

I HAD NEVER HEARD

of the mummies of

Pierre Jouguet, let alone the momentous discovery of the papyrus fragments wrapped around them, until a bone-chillingly cold afternoon in a guest room at

Lincoln College, Oxford. It was early January 1991, and I was deep into research for my book on Greek priestesses, fast on the trail of Queen

Praxithea. Huddled beside an electric fire, I opened Jan Bremmer’s

Interpretations of Greek Mythology

, keen to read Robert Parker’s article “Myths of Early Athens.” Within seconds I forgot the frosty chill of the guest room, enthralled by the tale of the Athenian king Erechtheus and how he sacrificed his daughter to save the city. Why had I never heard of this riveting story in my years of study? And how soon could I get my hands on a copy of Euripides’s text?

Lincoln College’s resident papyrologist,

Nigel Wilson, lived steps away in the front quad. He obligingly lent me his copy of

Nova fragmenta Euripidea

, which I carried across the Turl to the newsstand for photocopying. Holding the Kleine Texte edition down on the flashing glass of a first-generation Xerox machine, I watched as, page by page, Euripides’s

Erechtheus

spilled out in one long roll of slippery paper, strangely reminiscent of papyrus scrolls of the ancient past.

I carried the Xerox around with me for the better part of the next six months, working on the fragmentary Greek whenever I could steal a free moment, all the while waiting for a time when I could turn my full attention to the text. World events conspired to bring three full months of unexpected research time the following summer. As director of excavations on the island of

Yeronisos off western Cyprus, I usually head for the trenches in May to begin the summer field season. But the dig had to be canceled in 1991, because of

Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait and the ensuing

first Gulf War. Operation Desert Storm’s ground campaign had begun at the end of February, and by spring uncertainty still hung in the air. It was this unforeseen chain of events that grounded me Stateside for a full summer of unscheduled and uninterrupted research. Euripides’s

Erechtheus

was the first order of business.

Staring out the leaded windows of Bryn Mawr College’s classical seminar room in the Thomas Library, I fixed my eyes on the weeping cherry tree below. It was late afternoon, August 15, and I had finally

finished reading through the fragmentary Greek text. I was stunned by the power of

Praxithea’s patriotic speech and intrigued by Athena’s appointment of Praxithea as first

priestess of Athena Polias, and my mind’s eye turned to the central panel of the Parthenon’s east frieze. I had been poring over it all morning, trying to come to grips with the woman at its very center, the so-called priestess of Athena. Why didn’t she hold a temple key, the single attribute that would absolutely confirm her priestly status? Confirm, that is, if she were a historical priestess. But what if she were the first, mythical priestess of Athena, Queen Praxithea herself? Thus two independent lines of inquiry, both in pursuit of the priestess of Athena, collided in a single image shown on the east frieze. Could I be looking at what Euripides is talking about: a family group, with father, mother, and three daughters? And do I see Queen Praxithea, mother and priestess, at the very center of it all?

By November the following year, I stood face-to-face with

Colin Austin himself, there in the Cambridge University lecture hall where

Anthony Snodgrass had invited me to present my reinterpretation of the Parthenon frieze. I had set aside the priestess book and had worked on nothing else throughout the intervening fifteen months, devouring all I could find on

foundation myths, landscape,

memory, ritual, sacrifice, drama, democracy, and architectural sculpture. And now I met the man who had first recognized in

Sorbonne Papyrus 2328 the words of Euripides himself. Colin held in his hand the Kleine Texte volume containing the

Erechtheus

fragments. As we left with a band of students and faculty making our way to the post-lecture reception, he asked: “Would you like to read it together?” And when we had finished, seated there at the far end of the table of merrymakers, he turned and asked if I would care to read it again. So we went back to the beginning and read the play through for a second time. This was the first of many such encounters and the beginning of an enduring conversation. Colin never stopped learning from the

Erechtheus

fragments and encouraged me to do the same. His untimely

death in 2010 sadly brought an end to our wide-ranging discussions, but following his advice, I have continued to learn from all that this remarkably rich text has to teach.

AND SO I OFFER

a wholly new paradigm for understanding the Parthenon frieze, one that sees it as a representation of the great foundation myth from Athens’s legendary past.

57

Viewing the frieze against the backdrop of the story set out in Euripides’s

Erechtheus

, we can understand, for the first time, the momentous family portrait shown in the central panel of its east side. Mother, father, and three daughters have embarked on a supreme act of selfless love for their city, an act of ultimate sacrifice that exemplifies the core values upon which

Athenian democracy was built. The unthinkable will be demanded of this family, and yet its members will not be found wanting. They shall give their utmost for the community, laying aside self-interest to serve a greater, common good.

Erechtheus (second from right), Praxithea (center), and daughters preparing for sacrifice, east frieze, Parthenon. (illustration credit

ill.51

)

Understanding these figures as members of a family group enables us to perceive subtle adjustments in their heights, communicating that the three girls are sisters of three separate ages (above). The maiden at far left stands slightly shorter than the girl beside her, while the child at far right is shorter still.

58

Indeed, the “enigma” of this scene falls away as we recognize the Athenian royal family: Erechtheus, Praxithea, and their three daughters.

59

This portrait group would have been immediately recognizable to Athenians because of the distinctive presence of three girls. Most royal families in Greek myth had at least one treasured son. The Athenian dynasty was unusual for its abundance of daughters and scarcity of male heirs. As we have seen, by most accounts, Erechtheus had three daughters, as did Kekrops before him and Deukalion even earlier still. From its first days, then, the Acropolis was inhabited by a profusion of royal maidens. This is not surprising given that the patron of the city was a female divinity. There is a synergy and cohesion between the

virgin goddess of the city and the virgin daughters of its earliest kings.

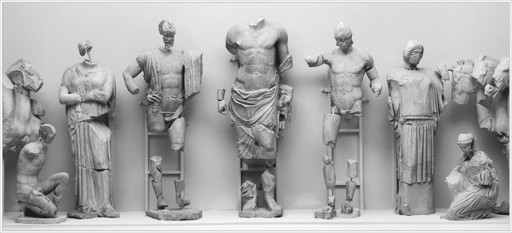

Royal family of Elis preparing for chariot race with Zeus at center, Queen Sterope and King Oinomaos at left, Pelops and Hippodameia at right. Olympia, east pediment. (illustration credit

ill.52

)

If we look to the greatest temple that immediately preceded the Parthenon, that of Zeus at Olympia completed in 456

B.C.

, we similarly find on its east end the local royal family in a solemn lineup (above).

60

King Oinomaos of Elis, his wife, Sterope, his daughter Hippodameia, and her suitor, Pelops, are shown in the pediment rather than on a frieze, but the parallel is nonetheless strong. The east façade of a temple is always its most significant: this is the location of the main entrance that faces the open-air altar upon which sacrifice was offered. Unlike in Christian churches, Greek

altars were located outside and to the east of temple buildings. This allowed the cult statue to look out through the front door, to watch and savor the

animal sacrifices offered to it. Importantly, having the front door at the east end of the temple allowed the rising sun to pour its radiance upon the icon of the divinity each morning. One must remember, the cult statue was no mere representation of the god but the divine presence itself.

Cult statues therefore needed to be awakened with first light, bathed, dressed, fed, and delighted with animal sacrifice, offerings, and gifts.

61

In keeping with the primacy of the east façade, we shall begin our

look at the Parthenon frieze here and work our way westward to the back of the temple. This, of course, is the reverse of the direction that pilgrims would have taken as they entered the Acropolis at the west and walked along the flanks of the Parthenon toward its east end. But this only serves to remind us that the intended primary viewer of the Parthenon sculptures was

Athena, not the human visitors. To make sense of the sculptures, then, we must read from the goddess’s point of view, beginning at the east, where our narrative starts.

62