The Parthenon Enigma (37 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

But whoever these men are, they are clearly related to the groups of maidens marching just beside them. Whether mythical kings, heroes, or generic Athenians from the legendary past, these men are likely to represent the fathers, uncles, brothers, or other male kin of the young women shown next to them at the far ends of the frieze (

this page

, previous page, and front of book). Juxtaposition of fathers and daughters would echo the special relationship of Erechtheus and his daughters featured in the central panel. It would also be a profound statement of the necessity for participation by citizens of all stations, both male and female, in securing the common good, the ultimate democratic virtue being to give oneself for the sake of the polis.

As we have seen in

chapter 3

, in 451/450

B.C.

Perikles introduced radical new legislation by which Athenian citizenship would pass only to those with both a mother and a father from citizen families. Previously, the honor passed through the father’s line alone. Men had been free to marry foreigners or non-Athenian Greeks and still have children who were citizens. But the Periklean citizenship law, by limiting the pool of marriageable prospects, gave a powerful new status to Athenian

women, now much sought after as brides.

141

The grouping of men and maidens on the east frieze of the Parthenon may express the newly mandated purity in the Athenian bloodline. By assuring that all citizens had two inherited ties to the land, being descended on both sides from the legendary ancestors, the new regime for legitimate marriage reinforced group solidarity and civic identity as never before.

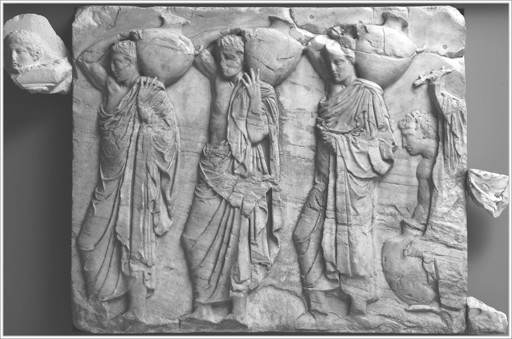

Maidens dominate the east frieze, thirteen at the north and sixteen at the south.

142

They march in pairs and carry libation bowls, jugs, and what may be incense burners. I maintain that they represent the sacred maiden choruses that Athena instructs Praxithea to establish in

memory of her deceased daughters. In the

Erechtheus

, Athena proclaims, “To my fellow citizens I say not to forget them over time but to honor them with annual sacrifices and bull-slaying slaughters, celebrating them with holy maiden dancing choruses.”

143

What we see are the mythical predecessors of the girls who would keep the all-night vigil for the Panathenaia, the

pannychis

, during historical times.

144

The fact that there are so many female figures, thirty-three in all, on the most important side of the temple speaks to the extraordinary significance of women in the foundational myth of Athenian identity.

LEAVING THE EAST FAÇADE

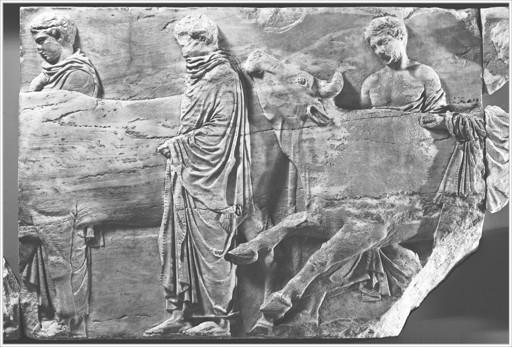

and turning the corners to the north and south sides of the Parthenon, we find

animals being led to sacrifice. On the south frieze there are ten cows and on the north frieze four cows and four rams (

this page

,

this page

,

this page

, and

this page

). Already in the

Iliad

bulls and rams are specified as offerings made to Erechtheus: “To him Athenian youth make sacrificial offerings, with bulls and rams as each year comes around.”

145

We will remember that at the end of the

Erechtheus

, Athena instructs that the deceased king be honored: “On account of his killer, he will be called, eponymously, Holy Poseidon-Erechtheus, by the citizens worshipping in cattle sacrifices.”

146

Two inscriptions found in Athens further attest to sacrifices made to Erechtheus. One mentions “a ram for Erechtheus,” and another, very fragmentary text mentions a “bull,” and just possibly, an “ox” or bull, and “a ram.”

147

Behind the animal offerings, on the north frieze, march three male offering bearers with trays (

skaphai

) and four youths carrying water jars (

hydriai

)

148

for the sacrifice (

this page

,

this page

, top,

this page

, and front of book). The south frieze (

this page

–

this page

), which has suffered so much damage, preserves just a fragment of one male tray bearer. This is enough, however, to suggest that there was a second group carrying trays here as well. The ninth-century lexicographer Photios tells us that the tray bearers were foreigners, resident aliens (

metoikoi

) at Athens, and that they wore purple chitons in the procession. Importantly, he tells us that the bronze and silver

skaphai

they carried were filled with honeycombs and cakes.

149

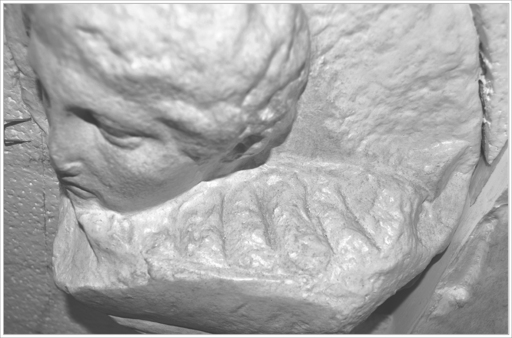

And indeed, in the tray of one

skaphephoros

from the north frieze we can make out textured cross-hatching very much like that of a honeycomb, best viewed in a plaster cast of the sculpture in Basel (

this page

, bottom, and

this page

, far left).

150

Youths leading cattle to sacrifice, north frieze, Parthenon. (illustration credit

ill.69

)

Honey is an offering associated with underground, chthonic deities, not Olympians like

Athena.

151

But in the

Erechtheus

, Athena unambiguously instructs that libations for the dead princesses should include only honey and water and

not

wine. The goddess ordains that prior to all battles the daughters of Erechtheus be propitiated: “Make to these, first, a preliminary sacrifice before taking up the spear of war, not touching the wine-making grape nor pouring on the pyre anything other than the fruit of the hardworking bee [honey] together with river water.”

152

The explicit combination of these two offerings carried by men bearing trays and men carrying heavy bronze water jugs on the Parthenon frieze surely refers to this special libation ordained by Athena for the daughters of Erechtheus.

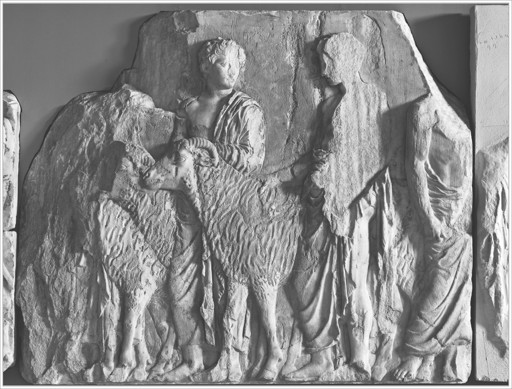

Youths leading ewes to sacrifice, north frieze, Parthenon. (illustration credit

ill.70

)

The goddess goes on to give instructions for the building of a shrine for the dead princesses, one with forbidden access: “It is necessary that these daughters have a precinct that must not be entered [

abaton

], and no one of the enemies should be allowed to make secret sacrifice there.”

153

We can now understand just why the chthonic gift of honeycomb is so appropriate for the daughters

of Erechtheus, buried as they are together in their common “earth-tomb.” The sisters have returned to

Gaia (Ge), from which their own father was born and to which he will unexpectedly return when swallowed by a chasm created by

Poseidon. Thus, Erechtheus leaves this world as he came into it, directly through Mother Earth.

A neat parallel for honey offerings in metal

hydriai

has been discovered at an underground sanctuary at Poseidonia (Paestum) in southern Italy: nine bronze water jugs filled with a molasses-like substance that appears to be honey, apparently deposited in the late sixth century

B.C

. The shrine was dedicated to a chthonic deity, most likely

Persephone—or, possibly, a group of

nymphs, to judge by a vase found nearby with the inscription “I am sacred to the nymphs.”

154

We should not forget that the daughters of Erechtheus are also children of the naiad nymph Praxithea, and thereby granddaughters of the river Kephisos. Libations of river water entirely befit their genealogy. Furthermore, the daughters of Erechtheus might have had their own special connection with Persephone. Like the Erechtheids, Persephone was just a maiden (Kore) when she was snatched into the underworld by Hades. According to Demaratus, it was Persephone who received the sacrifice of Erechtheus’s daughter. And at the very end of the

Erechtheus

, one line starts with the name “Demeter,” Persephone’s mother.

155

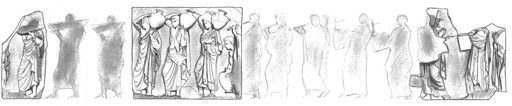

North frieze, Parthenon, surviving slabs and lost figures known from the Nointel Artist, showing tray and water jug bearers, pipe and lyre players, by George Marshall Peters. (illustration credit

ill.71

)

Returning to the frieze, we see musicians marching (above and

this page

) just behind the offering bearers. On the north side, these include four playing the

aulos

(a double reed, similar to the oboe) and four the

kithara

(a seven-stringed lyre). This stretch of the frieze was largely destroyed by the Venetian cannon fire of 1687, but it can be reconstructed, thanks to drawings the Nointel Artist made thirteen years earlier. And a few fragments of one kithara player survive in Athens to give us a sense of what the figures looked like. The comparable stretch on the south frieze is entirely missing. Some of this, too, was lost to the Venetian explosion and some of it deliberately cut out to make windows when the Parthenon became a cathedral in the thirteenth century. The drawings of the Nointel Artist are, once again, invaluable; they confirm a matching group of musicians here on the south side (

this page

, second row from bottom). Now Euripides explicitly refers to the aulos and kithara in a choral song from his

Erechtheus

, perhaps inspired by the musicians shown on the Parthenon frieze. The old men of the chorus ask, “Shall I ever shout through the city the glorious victory song, crying

‘Ie paian’

[an exclamation of triumph], taking up the task of my aged hand, the Libyan pipe sounding to the kithara’s cries?”

156

Plaster cast of tray bearer carrying honeycombs, figure N15, north frieze, Parthenon. (illustration credit

ill.72

)