The Parthenon Enigma (39 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

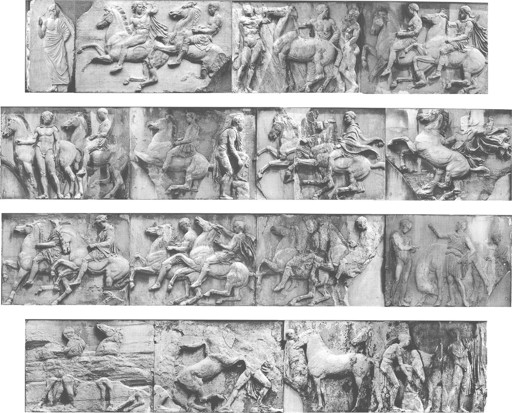

The west frieze is generally viewed as representing preparations for the Panathenaic procession (below). Frisking horses are held, mounted, and put through their paces by younger and older men. Iconographic parallels have been drawn between these figures and those shown on a series of Athenian red-figured cups.

177

The vases show young horsemen in a variety of costumes, including the wide-brimmed traveler’s hats, “coonskin” caps, and Thracian hats with flaps, the very same variety evident on the Parthenon frieze. The event depicted on the Attic cups has been identified as the

dokimasia

, an annual tryout of men and horses held by the Athenian cavalry, as described by

Aristotle.

178

A central element of the

dokimasia

was the testing of Athenian youths in their eighteenth year for acceptance into the military as ephebes. This is the age at which young men would enter their names upon deme registers as members of their tribes.

179

They swore their

Ephebic Oath upon

the arms they’d just received in the

sanctuary of Aglauros on the east slope of the Acropolis (insert

this page

, bottom).

180

This

oath, as discussed in

chapter 3

, was regarded as a relic of the heroic age, a rite of passage reaching back to the earliest days of Athens. In the images of the young riders on the Parthenon frieze, Athenians would likely have recognized the origins of their contemporary

ephebate

.

181

Indeed, the lofty status of the Athenian knights finds its roots in the

cavalry of King Erechtheus, the young noblemen who won the city’s first decisive victory in the battle against Eumolpos. We must remember that in the early sixth century, when

Solon reconfigured the citizenry in a first blueprint for what would become Athenian democracy, the

hippeis

class, made up of those who had enough money to maintain a horse and thus join the cavalry, ranked second only to the wealthiest of Athenian landowners.

West frieze, Parthenon, showing horse riders and preparation for the procession. (illustration credit

ill.79

)

THIS NEW MYTHOLOGICAL READING

of the Parthenon’s sculptural program allows it to be understood as a coherent whole and as comprehending the vast sweep of time embedded in Athenian consciousness. The east pediment celebrates the origins of Athena, while the east

metopes show the boundary event in which she first distinguished herself so valiantly: the

Gigantomachy. The west pediment celebrates the origins of Athens in the contest of Athena and

Poseidon, manifesting for all to see the genealogies of the royal houses of Athens and Eleusis. It emphasizes the descent of the Athenian tribes from Athena through Kekrops and Erechtheus and that of the Eleusinian clans from Poseidon through Eumolpos and

Keleos. The “

boundary catastrophe” of the

deluge is intimated by Poseidon’s striking the earth with his trident, furious at his defeat. The west metopes, in turn, show the later, heroic age in which

Theseus battles the Amazons, while the south metopes memorialize his decisive role in the Centauromachy. The north metopes manifest that greatest boundary event of all, the

Trojan War, which brought a decisive end to the Bronze Age, the final moment dividing mythical from historical time. The articulation and perpetuation of

genealogical narrative can thus be seen as a primary function of sacred architectural sculpture in general and of the Parthenon in particular.

182

Our mythological understanding of the frieze fits comfortably into this genealogical program, with the great carved band narrating the last Athenian hurrah of the heroic age: the war between Erechtheus and

Eumolpos. By portraying the struggles of successive generations against the forces of chaos and barbarism, the Parthenon’s sculptural program repeats a pattern already witnessed on the

Archaic Acropolis and discussed in

chapter 2

. The limestone pediments of the Hekatompedon and the small poros buildings (

oikemata

) present, respectively,

Zeus killing Typhon and Zeus’s son, Herakles, killing Typhon’s daughter, the

Lernaean Hydra. In the very same way, the conflict between

Athena and

Poseidon on the Parthenon’s west pediment is carried on by their children,

Erechtheus and Eumolpos, as depicted on the Parthenon frieze. And so have the Athenians, generation by generation, ensured a future for their city. As it was, so shall it ever be: the Parthenon’s full sculptural program is also, of course, a not-so-subtle metaphor for the Athenian triumph over the

Persians in 479

B.C.

183

It is the duty of all Athenians to save the city from exotic, barbaric outsiders, to preserve an Athens by and for the autochthonous Athenians: this is the central message of this supernal temple, where metaphysical understanding and civic solidarity are wedded for all to see. That the frieze shows the royal family itself personally paying the ultimate price to save Athens is of the highest significance, and not merely for offering a heroic contrast to the ways of the Persian royals, who survived the great defeat at Salamis. That the very founding family of Athens, from whom all are descended, could not put itself above the

common good speaks to a radical egalitarianism, not in circumstances, but in responsibility, the very antithesis of the barbarian sentiment that society exists for the exaltation of its most exalted members. All may not be equal in Athens, but all are equal in relation to this sacred trust, which comes of being bound to the same earth and to one another by birth. And this trust in one another is what permitted the delicate plant of democracy to take root.

ANGELOS CHANIOTIS

, professor of ancient history and classics at the

Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, has observed that “from

Plato to

Aelius Aristides, the praise of Athens was always based on a standard constellation of Athenian victories over the barbarians: the victory of Theseus over the Amazons, of Erechtheus over Eumolpos, and the

Persian Wars.” He asks, “Can the victory over Eumolpos, so prominent in Athenian collective

memory, be the only one absent from the

iconography of the Parthenon?”

184

Indeed, the Athenian victory over Eumolpos is not only present on the Parthenon; it is spectacularly celebrated in the largest, most lavish, and most aesthetically compelling length of sculpture ever carved by human hands.

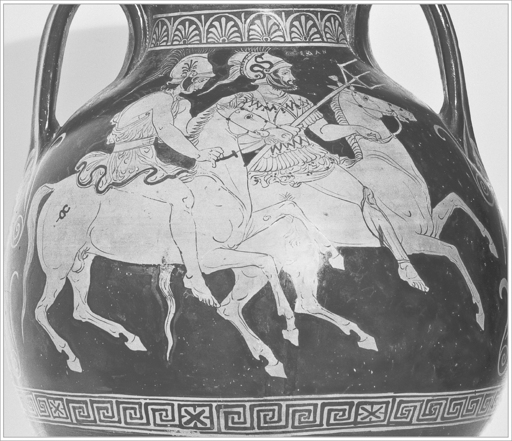

Poseidon and Eumolpos ride into battle. Lucanian pelike from Herakleia, near Policoro, Italy. (illustration credit

ill.80

)

When

Pausanias visited the Acropolis, he saw a big bronze statue group of Erechtheus fighting Eumolpos set up right in front of the Parthenon. He tells us that this was the most important work ever created by the master sculptor Myron of Eleutherai, that acclaimed portrayer of the so-called

Myronic moment of tension before the high action, as exemplified in his statue of the

Diskobolos

.

185

Since Myron was active in the middle of the fifth century, we can imagine his bronze Erechtheus in battle set just below the sculptured frieze on which his great victory was glorified.

By the fourth century

B.C.

, the war of Erechtheus and Eumolpos was so well known that it was painted on a vase produced in the Western Greek colony of Lucania in southern Italy. Vibrant images on this wine jar from Herakleia, near Policoro, portray the antagonists charging into battle.

186

On one side of the vase we see Poseidon, riding with trident held high and accompanied by an armed warrior who is, surely, his son Eumolpos (above). The father-son duo charge into battle astride

horses, creatures with which Poseidon always had a very special connection, having been known since the

Iliad

as the “tamer” of horses and, thanks to his creative coupling with mares, even as the “father” of some equines. In time, Poseidon acquires the epithet

Poseidon Hippios.

187

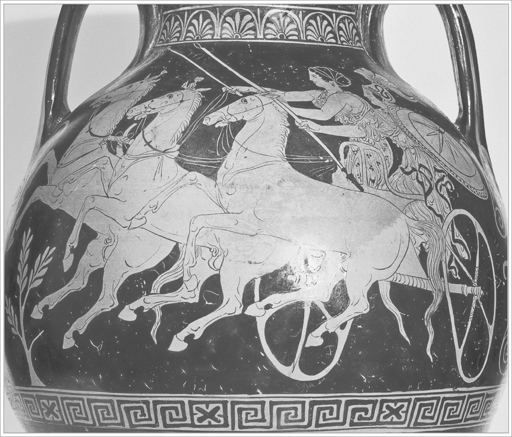

On the other side of the vase we see Athena, spear in one hand and shield in the other, as she is driven into battle on a chariot (below). Just as the horse is special to Poseidon, so the chariot is special to Athena as the vehicle introduced to Athens by her own “son,” Erechtheus/Erichthonios. The charioteer, however—and most astonishingly—is a maiden. The girl leans forward, holding her reins high and brandishing a whip, as she urges the yoked horses toward the battlefield. This maiden is likely to be none other than Erechtheus’s brave daughter, shown here as Athena’s comrade in the war against Eumolpos. Portraying Athena as a kind of

apobates

rider to the girl’s charioteer, the artist makes explicit the goddess’s intimate connection to the maiden called Parthenos, the girl who gave her life to save Athens.

The fact that the battle of Erechtheus and Eumolpos is not attested in surviving literature prior to Euripides’s

Erechtheus

has led some scholars to question whether it can be represented on the Parthenon frieze. Since Euripides wrote “a decade after the frieze was finished,” one skeptic argues, “the play cannot be the source of the sculpture.”

188

Of course it can’t, and no one has claimed that it is. As we have seen, the popularity of a particular myth, like that of its variants, can ebb and flow over time. It is even possible that the arrow of inspiration was shot the other way, with Euripides getting his idea from what he saw on the Parthenon frieze. What if those wordlessly eloquent images moved him to bring to the stage the very story most prominently narrated on his city’s newest and most wondrous temple? And what if the Erechtheus myth, reenergized in the wake of the

Persian Wars, was expanded to include a major victory over an exotic enemy, evoking that most recent, and greatest, of all Athenian triumphs? One can understand how the story of Erechtheus, elevated to a new prominence within Athenian consciousness, reached a peak in popularity at this time, celebrated in architectural sculpture, ritual practice, and, yes, drama. As

Perikles and the Athenians renewed their Acropolis, they embraced a reinvigorated hero, a fresh face for a fresh start.

Athena and daughter of Erechtheus ride into battle. Lucanian pelike from Herakleia, near Policoro, Italy. (illustration credit

ill.81

)

A false assumption that text precedes image has long bedeviled our understanding of visual culture. It is motivated, in part, by the mostly documentary and illustrative role that images play in our contemporary world, capturing moments in time as supplement to the main work of literary accounts. The field of classical archaeology has been particularly beset by this bias, going back to the days of

Heinrich Schliemann and earlier, when written texts were the primary guides and the archaeologist’s job was to search for material evidence to support what the texts say, just as Schliemann used the

Iliad

to discover the Troy and Mycenae of Homer. In a field shaped for centuries by philological inquiry, visual culture has invariably suffered, its distinctive grammar and stories neglected.