The Parthenon Enigma (35 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

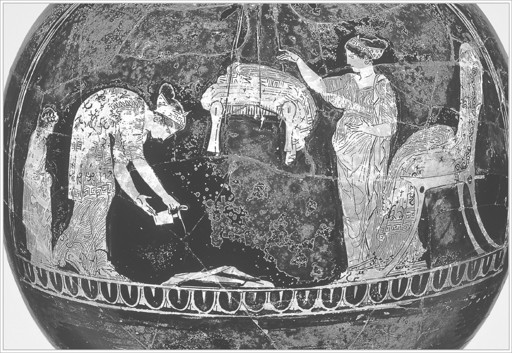

Women perfuming fabric on swinging stool. Oinochoe, Meidias Painter, ca. 420–410 B.C. (illustration credit

ill.59

)

In the Greek world, there were three great necessities for such elaborately woven fabrics: the baby’s

swaddling clothes, the bride’s wedding dress, and the corpse’s shroud. The word “peplos” applies to all three; indeed, it simply means an “uncut length of heavy woolen cloth.” Depending on the context, we find the word “peplos” translated as “robe,” “dress,” “tapestry,” “awning,” “swaddling clothes,” and “shroud.”

106

The

weaving of fabrics with figural designs took many months, even years, and would have been one of the chief occupations of women within the Greek household.

Penelope is the archetypal woman at the loom, painstakingly weaving (and unweaving) a shroud for her father-in-law,

Laertes, across the years of her husband’s absence, as recounted in the

Odyssey

. Shrouds were prepared well in advance, anticipating the

deaths of family members. Even to this day in certain Greek families, luxury sheets or embroidered cloths are set aside for the wrapping of bodies at the time of burial.

From antiquity through the Middle Ages, the shroud was a highly charged signifier, proof that a death had occurred. One need only think of the rich symbolism invested in the so-called

Shroud of Turin, which, forgery or not, has so potently symbolized the death and resurrection of Christ.

107

The presence of three shrouds in the central panel of the Parthenon frieze clearly communicates that three deaths are imminent. The stark white flesh of the youngest daughter, caught in the process of changing into her funerary dress, signals the impending tragedy is already in train, the time of sacrifice ineluctably near.

By this new reading we have three girls preparing for death (

this page

). The youngest goes first, so her peplos is being unfolded and displayed. The oldest daughter, second from left, is handing her stool to her mother. The daughter at far left stands frontally, her garment still folded and carried upon her head. According to the myth, the

oracle at Delphi had demanded the death of one daughter.

Apollodoros tells us this was to be the youngest of the three.

108

Praxithea and Erechtheus agree to that girl’s sacrifice, unaware that the sisters have pledged the

famous oath, that if one of them should die, so will the others. That the other two are shown carrying their own funeral dresses with unannounced plans of leaping from the Acropolis ironically foreshadows an even greater sacrifice than the parents expected to make.

What is the object cradled in the arm of the girl at far left? Though damaged and difficult to read, the shape of a lion’s paw has been deciphered at its lower right corner.

109

This has led to its identification as a footstool, presumably for use with one of the

stools carried by the girls.

110

Lion’s paws, however, are used to adorn not only footstools but the legs of small metal chests, including

jewelry boxes. Images from vase painting regularly show such boxes cradled in the arms of serving maids. Reading the frieze panel as a dressing scene prior to

virgin sacrifice, we can understand this object to hold the precious ornaments with which the maiden offering will be adorned.

111

The second-century

A.D.

orator

Aelius Aristides described the preparations for the sacrifice of Erechtheus and

Praxithea’s daughter as follows: “And her mother, dressing her up, led her just as if she were sending her to a spectacle.”

112

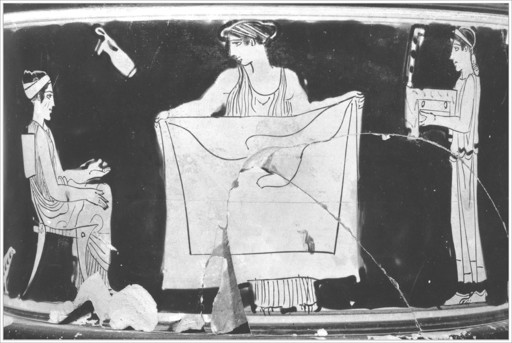

A red-figured pyxis in Paris provides an excellent parallel for this dressing scene. It shows preparations for the costuming of a maiden about to be married (below).

113

The bride is seated at the left and looks up at the wedding dress dramatically held out to her by a serving maid. At far right, a second servant carries a small metal box containing the bride’s jewelry, the finishing touches to her wedding

kosmos

. The same can be seen on the Parthenon’s east frieze. Father and sacrificial daughter display the funerary dress she is about to put on. At left, one of her sisters carries the box of jewelry with which she will be adorned just prior to her sacrifice.

Bridal

kosmos

with dress and jewelry displayed before bride. Pyxis, Painter of the Louvre Centauromachy, ca. 430 B.C. (illustration credit

ill.60

)

Andromeda dressed for sacrifice to sea dragon, Ethiopian servants bring clothing and jewelry. Pelike, workshop of the Niobid Painter, ca. 460 B.C. © 2014, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. (illustration credit

ill.61

)

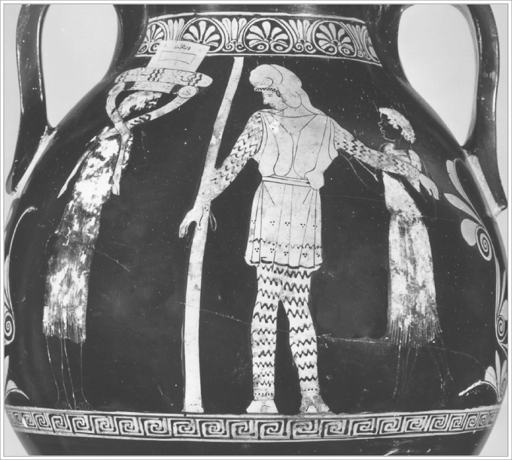

The princess Andromeda, lashed to stakes and left for an insatiable sea dragon, is depicted in Greek vase painting with very similar

iconography.

114

When a sea monster terrorized the Ethiopian coastline, the Delphic oracle proclaimed that the beast could be placated only through the sacrifice of the king’s daughter. And so Andromeda was led to a cliff overlooking the sea and chained to great rocks to prevent her from fleeing, should she not agree with her father’s act of selflessness. A red-figured vase in Boston shows the princess in her finest raiment and jewelry, ready to meet

death (above).

115

An Ethiopian servant approaches from the left, upon his head a folding stool with a small chest resting atop what appears to be a cushion but what surely represents the clean and carefully folded fabric

of Andromeda’s funerary dress.

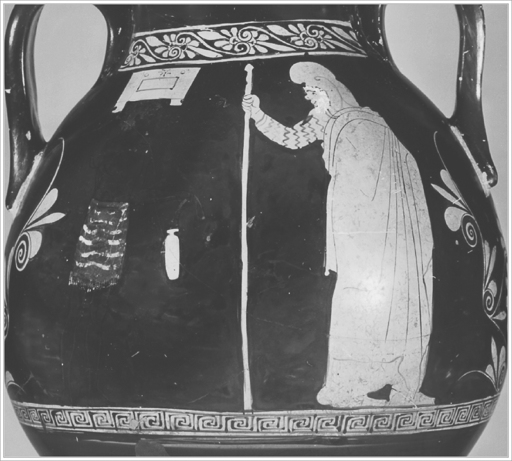

On the reverse of the vase (facing page), a second black attendant carries in even more trimmings for Andromeda’s

kosmos:

another jewelry box and a small jar of fragrant oil. Indeed, more is more when it comes to dressing up a

virgin victim for sacrifice. Andromeda’s forlorn father, King Kepheus, gravely supervises the preparations, rather as King Erechtheus does on the Parthenon frieze, creating the same excruciating anticipation. In both images, we have the tragic ambiguity of a dressing ritual equally befitting a wedding and a

virgin sacrifice.

King Kepheus oversees sacrifice of his daughter Andromeda; Ethiopian servant approaches. Pelike, ca. 460 B.C. © 2014, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. (illustration credit

ill.62

)

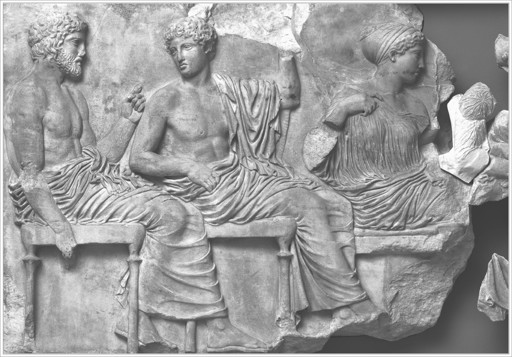

Two groups of six seated Olympians turn their backs on the central panel of the east frieze (

this page

,

this page

, and

this page

). To the south we see

Hermes,

Dionysos,

Demeter,

Ares,

Hera, and

Zeus. Just beside Hera stands a winged figure who is variously identified as Nike,

Iris, or

Hebe (goddess of youth).

116

At the north side we find

Athena,

Hephaistos,

Poseidon,

Apollo,

Artemis (following page),

Aphrodite, and a standing

Eros.

117

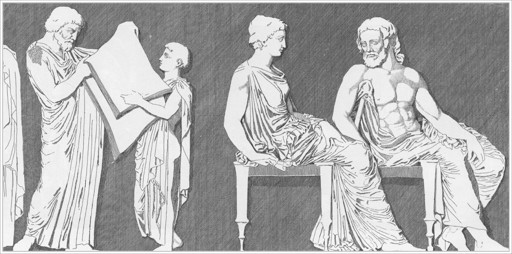

Strangely, the gods turn their backs on the goings-on of the central panel, looking out toward the groups of men and maidens filling the rest of the east frieze. Were this a historical Panathenaic procession, the gods would certainly be taking notice of the culminating moment of the ritual.

118

If it were the presentation of the peplos to Athena, the goddess would hardly be so indifferent to her own birthday offering. Athena’s body language would then suggest a callous rejection of her people’s gift (above), an event without sense or precedent.

119

Poseidon, Apollo, and Artemis, east frieze, slab 6, Parthenon. (illustration credit

ill.63

)

Erechtheus and daughter display fabric, Athena and Hephaistos turn away, east frieze, Parthenon. Stuart and Revett,

Antiquities of Athens

2: Pl. 23. (illustration credit

ill.64

)