The Parthenon Enigma (31 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

Importantly, Cyriacos gives the first documented identification of the Parthenon frieze as a depiction of a contemporaneous historical event, set in the fifth century

B.C.

He writes, “On the topmost friezes of the walls … the noted artist fashioned with outstanding skill [representations of] Athenian victories during

Perikles’s time.”

29

In this letter, Cyriacos invokes the issues that have dominated discussions of the Parthenon ever since: its status as a masterpiece; its authorship and the master sculptor Pheidias; a preoccupation with counting; and, of course, the reading of the frieze as a historical event, set in the days of Perikles. We must ask ourselves whether ancient Athenian viewers would have been preoccupied with these same matters, or whether they merely reflect the tastes and interests of the Italian Renaissance, during which Cyriacos lived.

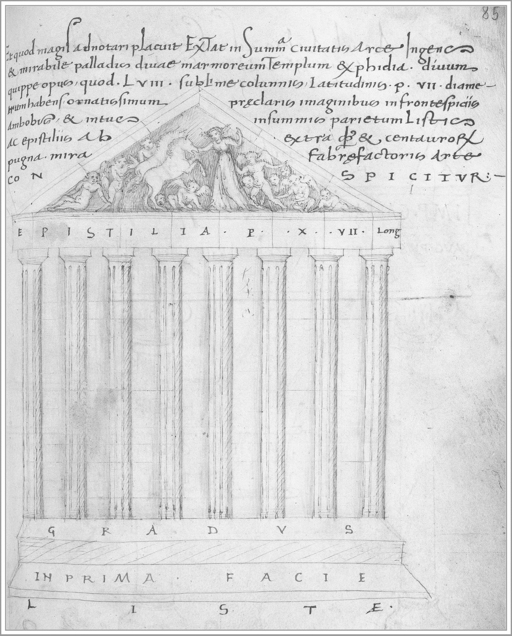

Cyriacos’s drawings suggest that the eye of the beholder very much shaped his vision of the Parthenon. They show distorted proportions and inaccurate placement of the sculptures in relation to the architecture. Fanciful additions, including winged cherubs crowding the west pediment, betray the influence of popular Renaissance types (above). The tall narrowness of his Parthenon, apparently set on a high podium, is more suited to a Roman temple than to a building of the classical Greek period. Cyriacos’s stylish Athena, shown struggling with frisking horses on his version of the west pediment, looks more like a wellborn lady of the quattrocento than a Greek goddess.

30

Her rival Poseidon has been wholly omitted from the composition.

Cyriacos of Ancona, copy of drawing of Parthenon’s west façade in silverpoint and ink. (illustration credit

ill.47

)

Cyriacos gets his numbers hopelessly wrong, too, from his calculations of the column diameters (5 feet), to the width of the peristyle corridors (8 feet), to the dimensions of the entablature beams (9.5 by 4 feet).

31

We must ask: Why have modern interpreters been happy to accept Cyriacos’s view of the Parthenon frieze as a representation of a

historical event even knowing that so many of his other observations are completely off the mark?

The Ottoman Turkish writer

Evliya Çelebi visited the Acropolis sometime between 1667 and 1669. Like Cyriacos, he saw the Parthenon very much through his own lens. This colorful courtier, musician, and litterateur recounted his expedition to Greece in the eighth of the ten volumes of his

Book of Travels (Seyahatname)

. This work has been described as “possibly the longest and most ambitious travel account by any writer in any language.”

32

By the time Çelebi visited Athens, the Parthenon had been transformed into a mosque, a consequence of the Ottoman conquest of 1458. “We have seen all the mosques of the world,” Çelebi writes, “but we have never seen the likes of this!” Çelebi is amazed by the “sixty tall and well-proportioned columns of white marble, laid out in two rows one above the other.”

33

He is equally impressed with four great columns of red porphyry set between the

prayer niche and the pulpit, beside which stand four additional columns of emerald-green marble. These colored columns were, no doubt, remnants of an earlier phase in the Parthenon’s reconfiguration, surviving from its days as a Christian basilica.

Çelebi’s enthusiasm for the Parthenon sculptures is palpable. “The human mind cannot indeed comprehend these images—they are white magic, beyond human capacity,” he writes. Extoling the “hundreds of thousands of works of art carved in white virgin marble,” he observes that “whoever looks upon them falls into ecstasy and his body grows weak and his eyes water for delight.”

34

Çelebi further reflects that in these sculptures the “human forms seem to be endowed with souls.” His imagination gets the better of him, however, when he attempts a catalog of the figures he sees. “Whatever living creatures the Lord Creator has created, from Adam to the Resurrection, are depicted in these marble statues around the courtyard of the mosque,” he writes. “Fearful and ugly demons, jinns, Satan the Whisperer, the Sneak, the Farter; fairies, angels, dragons, earth-beasts;…sea-beasts, elephants, rhinoceri, giraffes, horned vipers, snakes, centipedes, scorpions, tortoises, crocodiles, sea-sprites; thousands of mice, cats, lions, leopards, tigers, cheetahs, lynxes; ghouls, cherubs.”

35

The mind reels attempting to reconcile Çelebi’s report of this fantastical menagerie with what we know of the Parthenon sculptures today.

It is, however, the expedition of the artist

James Stuart and the amateur

architect Nicholas Revett, organized on behalf of the Society of Dilettanti from 1751 to 1753, that has had the most lasting impact on our understanding of the Parthenon sculptures. The English travelers surveyed, calculated, and drew the Parthenon, presenting their work in a sumptuous multivolume publication,

The Antiquities of Athens: Measured and Delineated

.

36

In volume 2, published in 1787, the authors present drawings of the Parthenon frieze, offering as well an interpretation of what it depicts: the Panathenaic procession.

37

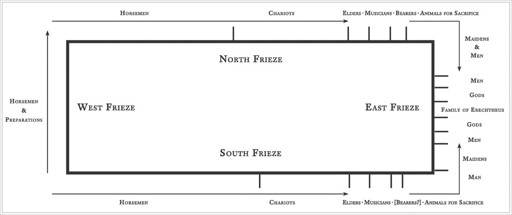

Stuart and Revett identified the cavalcade and chariots moving from west to east along the flanks of the Parthenon as the Athenian army following behind bearers of offerings, musicians, maidens, elders, and those who lead animals to sacrifice (below and

this page

–

this page

and front of book). In the eyes of Stuart and Revett, the marchers collectively represent the Athenian citizenry celebrating the great city feast of the Panathenaia.

38

The procession marches toward gods seated either side of a group of five mortals at the very center of the east frieze, positioned just above the door of the temple. We see a woman with two girls, at left, and a man and a child holding a piece of cloth, at right (

this page

and

this page

and front of book). The identification of this scene rests firmly on the assumption that the cloth displayed is the sacred dress, or peplos, of Athena, a gift presented to the goddess as the culminating event of the Panathenaic

ritual. But Stuart and Revett first advanced this idea only tentatively and as a query: “May we not suppose this folded cloth to represent the peplos?”

39

Over time, their gentle question has hardened into established dogma.

Parthenon frieze, sequence and direction of procession. (illustration credit

ill.48

)

Seldom has this view been challenged over the past 220 years, though it has presented enormous difficulties for a coherent reading of the frieze. This central panel of the east frieze has long been called the “peplos scene” or sometimes even the “enigmatic peplos incident,” a highly unsatisfactory name for what plainly seems to be the climax of the entire composition,

40

prominently set above the main door of the temple, where anyone entering might look up and see it. Interpreters have struggled to understand whether the image shows the presentation of the new peplos to Athena or the folding up and putting away of the old peplos.

41

This second view would certainly be something of an anticlimax, obliging us to ask why there might be such a postlude in what should be a place of culmination and central meaning.

Scholars have assembled lists of all the elements we should expect to find in a Panathenaic procession, gathered from sources of late classical through Byzantine date. But their lists do not match what we see on the Parthenon.

42

We know that a wellborn maiden, called a

kanephoros

after the basket, or

kanoun

, that she carried, was chosen to lead the Panathenaic procession.

43

But we see no basket bearer on the frieze.

44

Athenian allies are known to have served as tribute bearers in the procession and resident foreign women as water bearers. These, too, however, are absent. At least from the fourth century

B.C

. but probably even earlier, a wheeled ship-cart transported the peplos, hoisted like a sail up its mast, as it made its way in procession through the Agora and up the Sacred Way to the Acropolis. But this spectacle is nowhere to be seen on the frieze.

45

Above all, we miss the

hoplites, the famous foot soldiers who were the heart and soul of the Athenian army from the Archaic period on.

46

If the Parthenon frieze does indeed show a fifth-century Athenian army, the hoplites could not conceivably be omitted.

Equally strange is the presence of figures we would not expect to find in a Panathenaic procession. We see men bringing heavy water jars (

this page

and

this page

and front of book), when we know that it was foreign women who carried water for the Panathenaia.

47

Even more troubling is the anachronistic appearance of chariots, which had not been used in Greek warfare since the Late

Bronze Age, some seven hundred years earlier.

48

The reading of the frieze as a contemporary event set in the fifth century

B.C

. would also propose a singular exception to all conventions for Greek temple decoration, which consistently derived its subject matter from myth.

49

Indeed, recent work on the

function of images in ancient Greece has stressed their primary role as vehicles to help us see what could no longer be seen, that is, the legendary days of the mythical past.

50

Visual representations served as markers of memory (

hypomnemata

or

mnemeia

) for what once was, and so it seems strange to memorialize the same spectacle that could be observed in the flesh each year at the Small Panathenaia or every fourth year (on a grander scale) at the Great Panathenaia. It would not square even with the rest of the Parthenon’s sculptural program. The pediments indisputably show the birth of Athena and the contest of Poseidon and Athena for patronage of the city. Its metopes show gods battling Giants and Greeks fighting Amazons, Centaurs, and Trojans. Why should the frieze depart from this otherwise mythological program?

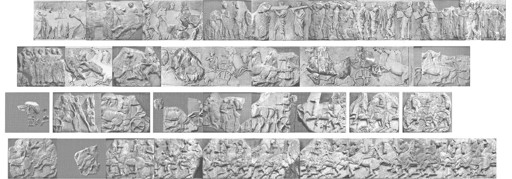

North frieze, Parthenon, showing animals led to sacrifice, offering bearers, musicians, elders, chariots, and horsemen. (illustration credit

ill.49

)

This was a question asked repeatedly by the architectural historian A. W. Lawrence, who followed his famous older brother, T. E. Lawrence, in the study of archaeology at Oxford. Arnold went on to hold the Laurence Chair in Classical Archaeology at Cambridge from 1944 to 1951. Many of Arnold Lawrence’s perspicacious insights have stood the test of time, above all his concern for the anomaly posed by the traditional reading of the Parthenon frieze. “This must have verged on profanation,” he writes in his 1951 article “The Acropolis and Persepolis.” “At every other Greek temple the sculpture illustrates mythological scenes.”

51

Twenty years later, Lawrence reiterated this concern: “Never before had a contemporary subject been treated on a religious building and no subsequent Greek instance is known … The flagrant breach with tradition requires explanation.”

52