The Parthenon Enigma (15 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

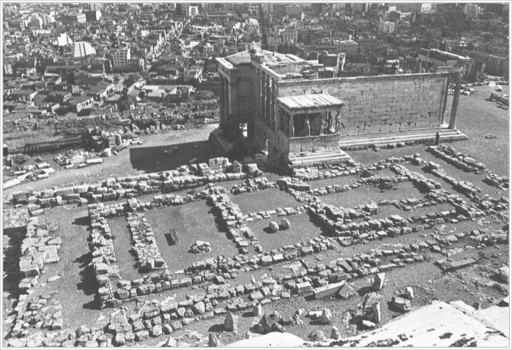

The Gigantomachy took pride of place on the great gable of the Archaios Neos or Old Athena Temple, a structure built at the north side of the Acropolis at the turn of the sixth to the fifth century.

84

The temple rose from the so-called

Dörpfeld foundations, still visible today (below, and see also

this page

and insert

this page

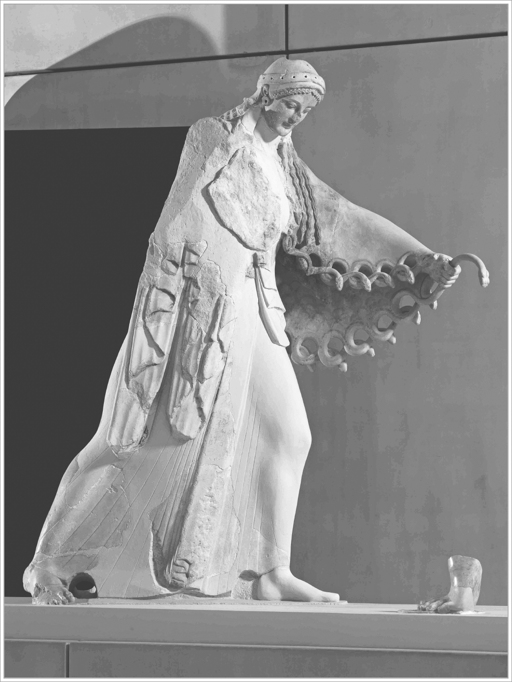

, bottom). Its pediments were filled with colossal figures carved in expensive marble imported from the island of Paros. One of the gables showed lions savaging a bull just as on the old Bluebeard Temple. The other pediment featured the Gigantomachy, dominated by a dynamic image of Athena lunging toward a fallen giant (following page). The goddess is shown in feverish pursuit of the enemy, employing her snaky aegis not only as a shield but also as a weapon. She manipulates a hissing, biting snake head, using it to menace a fallen giant.

85

Erechtheion and foundations of Old Athena Temple, from south. (illustration credit

ill.17

)

Athena from Gigantomachy pediment, Old Athena Temple. Athens, Acropolis Museum. (illustration credit (illustration credit

ill.18

)

Athena slaying giant, Gigantomachy pediment, Old Athena Temple. Athens, Acropolis Museum.

ill.19

)

Charioteer from frieze (?), Old Athena Temple. Athens, Acropolis Museum. (illustration credit

ill.20

)

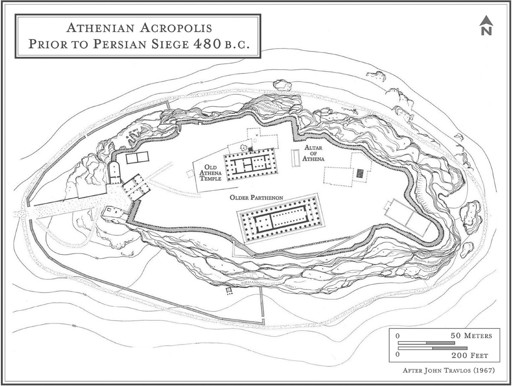

This bold composition crowned a

Doric temple that measured roughly 21 by 43 meters (69 by 141 feet) and showed six columns across the façades and twelve down its flanks (following page and insert

this page

, bottom).

86

Built of poros limestone quarried in the Piraeus, the Old Athena Temple was adorned with marble roof tiles, gutters, akroteria, lion’s-head waterspouts, and metopes.

87

It seems also to have been decorated with a marble frieze of which little survives: one fragment clearly shows the god

Hermes and another, a charioteer (above).

88

As we shall see in

chapter 5

, chariots had very special meaning at Athens since being introduced into Athenian warfare by the founder, King Erechtheus/ Erichthonios himself.

The

plan of the Old Athena Temple was unusual as the main room at the east was completely separated from the three rooms at the back or west end of the structure (above and

this page

). Its eastern cella had two rows of three columns dividing the interior into three “aisles.” Here, an olive wood statue of Athena was housed, known as the “ancient image” (

to archaion agalma

). This relic, believed to have fallen from the heavens in the early days of Athens, was the most sacred object in the city. It was aniconic (an effigy without human shape), consisting of a simple olive wood tree trunk.

89

Like cult statues in all Greek sanctuaries, the image was regarded not as a representation of the deity but as the divine essence itself. Therefore, Athena’s statue was dressed in ornate fabric and adorned with a golden diadem, earrings, necklaces, and bracelets. It even had its own gold libation bowl.

90

Once a year the statue would be taken down to the sea at Phaleron for bathing before returning to its “house” on the Acropolis.

Plan of Athenian Acropolis in 480 B.C. (illustration credit

ill.21

)

The back of the Old Athena Temple was separated from the eastern room by a dividing wall and comprised an anteroom opening onto two smaller chambers, accessible through a single entrance on the west porch. This curious plan seems to reflect the integration of three distinct cult places and anticipates the unusual subdivision of the structure that would “replace” it in the last quarter of the fifth century, the Erechtheion (

this page

,

this page

,

this page

, and

this page

). Indeed, the Erechtheion reserves special cult places for Athena at the east and for Poseidon, Erechtheus, and his brother Boutes at the west, indicating that this building, like its predecessor, was devoted to the joint worship of multiple gods and heroes.

91

Two rough limestone column bases found embedded in the foundations of the Old Athena Temple (

this page

) in 1885 may be remnants of an even earlier incarnation of the shrine dating to the first half of the seventh century.

92

These bases would have held wooden columns supporting a superstructure of mud brick. This temple, or perhaps an even earlier (albeit hypothetical) eighth-century predecessor, may be the shrine of which

Homer speaks when he says that Erechtheus “entered the rich temple of Athena” on the Acropolis.

93

This is likely to have been the temple where

Kylon took refuge in his failed coup attempt during the 630s. Interestingly, this seventh-century shrine was

called the Old Temple (Archaios Neos), just like the building that replaced it. All these incarnations of Athena’s holy precinct (hypothetical eighth-century shrine, seventh-century temple, Old Athena Temple, and

Erechtheion) sat upon the site of the

Bronze Age

Mycenaean palace (

this page

), making visible in perpetuity a bond with the heroic past. (At other sites, like Mycenae and

Tiryns,

Iron Age temples are built atop or near the “big room” or “megaron” of the local palace’s remains.)

94

A small bronze cutout relief (previous page) may give a hint at the decoration of the seventh-century Athena temple.

95

We see the terrorizing face of

Medousa, the Gorgon sister, sticking out her tongue and baring her sharp incisors. If one imagines also the horrifying screech the

Gorgons were thought to make, one can re-create the effect meant to scare away any force of sinister intent.

Bronze Gorgon akroterion (?), from Acropolis, seventh century B.C. Athens, Acropolis Museum. (illustration credit

ill.22

)

IN ADDITION TO

the construction of the Old Athena Temple, the early years of Athenian democracy might also have witnessed the inception of a second new structure on the Acropolis, set just to the south and roughly parallel to Athena’s shrine. On the very spot where the Bluebeard Temple might have stood, a massive platform of nearly ten thousand limestone blocks was laid in preparation for the building of a new temple, sometimes called the Grandfather of the Parthenon, or Parthenon I, by Dörpfeld,

Manolis Korres, and other scholars.

96

But a contrasting view dates the foundations much later, after the

battle of Marathon in 490, when they would have been positioned to support the immediate predecessor of the Parthenon, a building simply referred to as the

Older Parthenon.

97

These foundations, constructed of limestone blocks quarried 10 kilometers (6 miles) away in the Piraeus and set some twenty-one courses deep on its south side, represent an enormous undertaking in anticipation of a huge new structure.

If this platform was already laid at the end of the sixth or early fifth century, it might have been that the young democracy wished to replace the Bluebeard Temple, tainted as it might have been with links to the Peisistratid

tyranny. With a new regime dawning, memories of the disastrous ending of the old administration had to be expunged. After all, the tyrant

Hippias was now ensconced with the Persians, and his

memory was one thing that need not be preserved in stone. Any thought of finishing his giant temple of Olympian Zeus near the Ilissos

was abandoned when his tyranny came to an end. So it might have been that the Bluebeard Temple was regarded as a monument in need of replacing. In any event, if there was a plan for a new temple to replace the Hekatompedon, it was not yet to be realized.