The New Penguin History of the World (65 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

The translation of books from Arabic to Latin was of huge importance to Christendom. By the end of the twelfth century most of Aristotle was available in Latin, many of the works having come by this route. The admiration and repute of Arab writers among Christian scholars was a recognition of its importance. Of the works of Al-Kindi, one of the greatest of Arab philosophers, more survive in Latin than in Arabic, while Dante paid Ibn-Sina (Avicenna in Europe) and Averroes the compliment of placing them in limbo (together with Saladin, the Arab hero of the crusading epoch) when he allocated great men to their fate after death in his poem,

The Divine Comedy

, and they were the only men of the Christian era whom he treated thus. The Persian practitioners who dominated Arabic medical studies wrote works which remained for centuries standard textbooks of western training. European languages are still marked by Arabic words which indicate the special importance of Arabic study in certain areas: ‘zero’, ‘cipher’, ‘almanac’, ‘algebra’ and ‘alchemy’ are among them. The survival of a technical vocabulary of commerce, too – tariff,

douane

, magazine – is a reminder of the superiority of Arab commercial technique; the Arab merchants taught Christians how to keep accounts. One English king minted his gold coins on the pattern of Muslim dinars.

Strikingly, this cultural traffic was almost entirely one way. Only one Latin text, it appears, was ever translated into Arabic during the Middle Ages, at a time when Arabic scholars were passionately interested in the

cultural legacies of Greece, Persia and India. A single fragment of paper bearing a few German words with their Arabic equivalents is the only evidence from eight hundred years of Islamic Spain of any interest in western languages outside the peninsula. The Arabs regarded the civilization of the cold lands of the north as a meagre, unsophisticated affair, as no doubt it was. But Byzantium impressed them.

An Arabic tradition in visual art founded under the Umayyads also flourished under the Abbasids, but it was narrower in its scope than Islamic science. Islam came to forbid the making of likenesses of the human form or face; this was not scrupulously enforced, but it long inhibited the appearance of naturalistic painting or sculpture. Of course, it did not restrict architects. Their art developed very far within a style whose essentials had appeared at the end of the seventh century; it was at once in debt to the past and unique to Islam. The impression produced upon the Arabs by Christian building in Syria was the catalyst; from it they learnt, but they sought to surpass it, for believers should, they were sure, have places of worship better and more beautiful than the Christians’ churches. Moreover, a distinctive architectural style could visibly serve as a separating force in the non-Muslim world which surrounded the first Arab conquerors of Egypt and Syria.

The Arabs borrowed Roman technique and Hellenistic ideas of internal space, but what resulted was distinctive. The oldest architectural monument of Islam is the Dome of the Rock built at Jerusalem in 691. Stylistically, it is a landmark in architectural history, the first Islamic building with a dome. It appears to have been built as a monument to victory over Jewish and Christian belief, but unlike the congregational mosques which were to be the great buildings of the next three centuries, the Dome of the Rock was a shrine glorifying and sheltering one of the most sacred places of Jew and Muslim alike; men believed that on the hill-top it covered Abraham had offered up his son Isaac in sacrifice and that from it Muhammad was taken up into heaven.

Soon afterwards came the Umayyad mosque at Damascus, the greatest of the classical mosques of a new tradition. As so often in this new Arab world, it embodied much of the past; a Christian basilica (which had itself replaced a temple of Jupiter) formerly stood on its site, and it was itself decorated with Byzantine mosaics. Its novelty was that it established a design derived from the pattern of worship initiated by the Prophet in his house at Medina; its essential was the

mihrab

, or alcove in the wall of the place of worship, which indicated the direction of Mecca.

Architecture and sculpture, like literature, continued to flourish and to draw upon elements culled from traditions all over the Near East and Asia.

Potters strove to achieve the style and finish of the Chinese porcelain, which came to them down the Silk Road. The performing arts were less cultivated and seem to have drawn little on other traditions, whether Mediterranean or Indian. There was no Arab theatre, though the story-teller, the poet, the singer and the dancer were esteemed. Arabic musical art is commemorated in European languages through the names of lute, guitar and rebec; its achievements, too, have been seen as among the greatest of Arabic culture, though they were to remain less accessible to western sensibility than those of the plastic and visual arts.

Many of the greatest names of this civilization were writing and teaching when its political framework was already in decay, even visibly collapsing. In part this was a matter of the gradual displacement of Arabs within the caliphate’s élites, but the Abbasids in their turn lost control of their empire, first of the peripheral provinces and then of Iraq itself. As an international force they peaked early; in 782 an Arab army appeared for the last time before Constantinople. They were never to get so far again. Haroun-al-Raschid might be treated with respect by Charlemagne but the first signs of an eventually irresistible tendency to fragmentation were already there in his day.

In Spain, in 756, an Umayyad prince, who had not accepted the fate of his house, had proclaimed himself

emir

, or governor, of Córdoba. Others were to follow in Morocco and Tunisia. Meanwhile, El-Andalus acquired its own caliph only in the tenth century (until then its rulers remained emirs) but long before that was independent

de facto

. This did not mean that Umayyad Spain was untroubled. Islam had never conquered the whole peninsula and the Franks recovered the north-east by the tenth century. There were by then Christian kingdoms in northern Iberia and they were always willing to help stir the pot of dissidence within Arab Spain where a fairly tolerant policy towards Christians did not end the danger of revolt.

Yet El-Andalus, though not embracing all Iberia, prospered as the centre of a Muslim world. The Umayyads developed their sea-power and contemplated imperial expansion not towards the north, at the expense of the Christians, but into Africa, at the expense of Muslim powers, even negotiating for alliance with Byzantium in the process. It was not until the eleventh and twelfth centuries, when the caliphate of Córdoba was in decline, that Spain’s Islamic civilization reached its greatest beauty and maturity in a golden age of creativity which rivalled that of Abbasid Baghdad. This left behind great monuments as well as producing great learning and philosophy. The seven hundred mosques of tenth-century Córdoba numbered among them one which can still be thought the most beautiful building in the world – the Mezquita. Arab Spain was of enormous importance to

Europe, a door to the learning and science of the East, but one through which were also to pass more material goods as well: through it Christendom received knowledge of agricultural and irrigation techniques, oranges and lemons, sugar. As for Spain itself, the Arab stamp went very deep, as many students of the later, Christian, Spain have pointed out, and can still be observed in language, manners and art.

Another important breakaway within the Arab world came when the Fatimids from Tunisia set up their own caliph and moved their capital to Cairo in 973. The Fatimids were Shi’ites and maintained their government of Egypt until a new Arab invasion destroyed it in the twelfth century. Less conspicuous examples could be found elsewhere in the Abbasid dominions as local governors began to term themselves emir and sultan. The power base of the caliphs narrowed more and more rapidly; they were unable to reverse the trend. Civil wars among the sons of Haroun led to a loss of support by the religious teachers and the devout. Bureaucratic corruption and embezzlement alienated the subject populations. Recourse to tax-farming as a way around these ills only created new examples of oppression. The army was increasingly recruited from foreign mercenaries and slaves; even by the death of Haroun’s successor it was virtually Turkish. Thus, barbarians were incorporated within the structure of the caliphates as had been the western barbarians within the Roman empire. As time went by they took on a praetorian look and increasingly dominated the caliphs. And all the time popular opposition was exploited by the Shi’ites and other mystical sects. Meanwhile, the former economic prosperity waned. The wealth of Arab merchants was not to crystallize in a vigorous civic life such as that of the late medieval West.

Abbasid rule effectively ended in 946 when a Persian general and his men deposed a caliph and installed a new one. Theoretically, the line of Abbasids continued, but in fact the change was revolutionary; the new Buwayhid dynasty lived henceforth in Persia. Arab Islam had fragmented; the unity of the Near East was once more at an end. No empire remained to resist the centuries of invasion which followed, although it was not until 1258 that the last Abbasid was slaughtered by the Mongols. Before that, Islamic unity had another revival in response to the Crusades, but the great days of Islamic empire were over.

The peculiar nature of Islam meant that religious authority could not long be separated from political supremacy; the caliphate was eventually to pass to the Ottoman Turks, therefore, when they became the makers of Near-Eastern history. They would carry the frontier of Islam still further afield and once again deep into Europe. But their Arab predecessors work was awe-inspiringly vast for all its ultimate collapse. They had destroyed both the old Roman Near East and Sassanid Persia, hemming Byzantium in to Anatolia. In the end, though, this would call western Europeans back into the Levant. The Arabs had also implanted Islam ineradicably from Morocco to Afghanistan. Its coming was in many ways revolutionary. It kept women, for example, in an inferior position, but gave them legal rights over property not available to women in many European countries until the nineteenth century. Even the slave had rights and inside the community of the believers there were no castes nor inherited status. This revolution was rooted in a religion which – like that of the Jews – was not distinct from other sides of life, but embraced them all; no words exist in Islam to express the distinctions of sacred and profane, spiritual and temporal, which our own tradition takes for granted. Religion

is

society for Muslims, and the unity this has provided has outlasted centuries of political division. It was a unity both of law and of a certain attitude; Islam is not a religion of miracles (though it claims some), but of practice and intellectual belief.

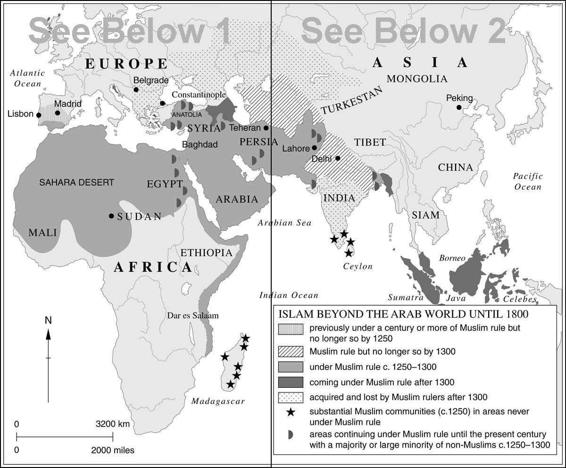

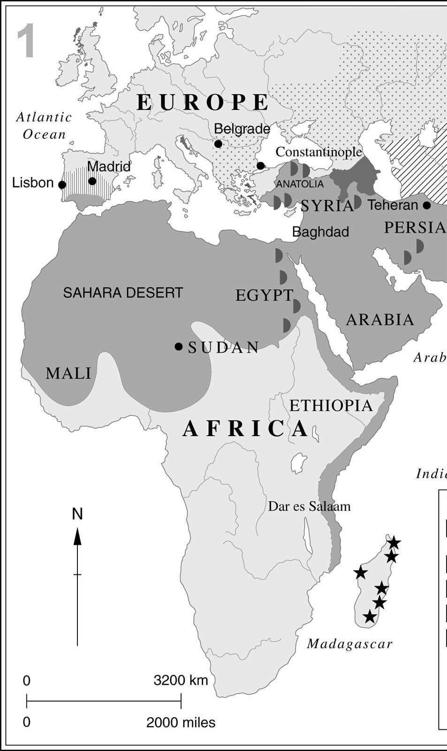

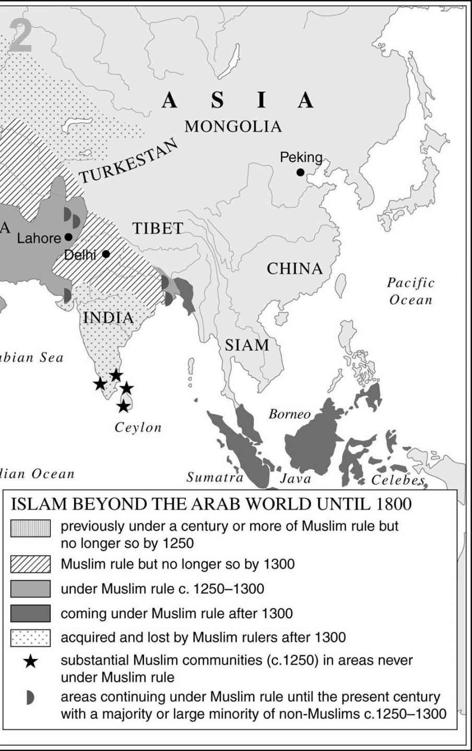

Besides having a great political, material and intellectual impact on Christendom, Islam also spread far beyond the world of Arab hegemony, to central Asia in the tenth century, India between the eighth and eleventh and in the eleventh beyond the Sudan and to the Niger. Between the twelfth

and sixteenth centuries still more of Africa would become Muslim; Islam remains today the fastest-growing faith of that continent. Thanks to the conversion of Mongols in the thirteenth century, Islam would also reach China. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries it spread across the Indian ocean to Malaya and Indonesia. Missionaries, migrants and merchants carried it with them, the Arabs above all, whether they moved in caravans into Africa or took their dhows from the Persian Gulf and Red Sea to the bay of Bengal. There would even be a last, final extension of the faith in south-east Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. It was a remarkable achievement for an idea at whose service there had been in the beginning no resources except those of a handful of Semitic tribes. But in spite of its majestic record no Arab state was ever again to provide unity for Islam after the tenth century. Even Arab unity was to remain only a dream, though one cherished still today.