The New Penguin History of the World (61 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

1

Islam and the Remaking of the Near East

With relatively brief interruptions, great empires based in Iran hammered away at the West for a thousand years before 500. Wars sometimes bring civilizations closer, and in the Near East two cultural traditions had so influenced one another that their histories, though distinct, are inseparable. Through Alexander and his successors, the Achaemenids had passed to Rome the ideas and style of a divine kingship whose roots lay in ancient Mesopotamia; from Rome they went on to flower in the Byzantine Christian empire which fought the Sassanids. Persia and Rome fascinated and, in the end, helped to destroy one another; their antagonism was a fatal commitment to both of them when their attention and resources were urgently needed elsewhere. In the end both succumbed.

The first Sassanid, Ardashir, or Artaxerxes, had a strong sense of continuing Persian tradition. He deliberately evoked memories of the Parthians and the Great King, and his successors followed him in cultivating them by sculpture and inscription. Ardashir claimed all the lands once ruled by Darius and went on himself to conquer the oases of Merv and Khiva, and invade the Punjab; the conquest of Armenia took another hundred and fifty years to confirm but most of it was in the end brought under Persian hegemony. This was the last reconstitution of the ancient Iranian empire and in the sixth century it even stretched south as far as the Yemen.

Geographical and climatic variety always threatened this huge sprawl of territory with disintegration, but for a long time the Sassanids solved the problems of governing it. There was a bureaucratic tradition running back to Assyria to build on and a royal claim to divine authority. The tension between these centralizing forces and the interests of great families was what the political history of the Sassanid state was about. The resultant pattern was of alternating periods of kings encumbered or unsuccessful in upholding their claims. There were two good tests of this. One was their ability to appoint their own men to the major offices of state and resist the claims on them of the nobility. The other was their retention of control over the succession. Some Persian kings were deposed and though the

kingship itself formally passed by nomination by the ruler, this gave way at times to a semi-electoral system in which the leading officers of state, soldiers and priests made a choice from the royal family.

The dignitaries who contested the royal power and often ruled in the satrapies came from a small number of great families which claimed descent from the Parthian Arsacids, the paramount chiefs of that people. They enjoyed large fiefs for their maintenance but their dangerous weight was balanced by two other forces. One was the mercenary army, largely officered by members of the lesser nobility, who were thus given some foothold against the greater. Its corps d’élite, the heavy-armed household cavalry, was directly dependent on the king. The other force was the priesthood.

Sassanid Persia was a religious as well as a political unity. Zoroastrianism had been formally restored by Ardashir, who gave important privileges to its priests, the

magi

. They led in due course to political power as well. Priests confirmed the divine nature of the kingship, had important judicial duties, and came, too, to supervise the collection of the land-tax which was the basis of Persian finance. The doctrines they taught seem to have varied considerably from the strict monotheism attributed to Zoroaster but focused on a creator, Ahura Mazda, whose viceroy on earth was the king. The Sassanids’ promotion of the state religion was closely connected with the assertion of their own authority.

The ideological basis of the Persian state became even more important when the Roman empire became Christian. Religious differences began to matter much more; religious disaffection came to be seen as political. The wars with Rome made Christianity treasonable. Though Christians in Persia had at first been tolerated, their persecution became logical and continued well into the fifth century. Nor was it only Christians who were tormented. In 276 a Persian religious teacher called Mani was executed – by the particularly agonizing method of being flayed alive. He was to become known in the West under the Latin form of his name, Manichaeus, and the teaching attributed to him had a future as a Christian heresy. Manichaeism brought together Judaeo-Christian beliefs and Persian mysticism and saw the whole cosmos as a great drama in which the forces of light and darkness struggled for domination. Those who apprehended this truth sought to participate in the struggle by practising austerities which would open to them the way to perfection and to harmony with the cosmic drama of salvation. Manichaeism sharply differentiated good and evil, nature and God; its fierce dualism appealed to some Christians who saw in it a doctrine coherent with what Paul had taught. St Augustine was a Manichee in his youth and Manichaean traces have been detected much later in the heresies of medieval Europe. Perhaps an uncompromising dualism has always a strong appeal to a certain cast of mind. However that may be, the distinction of being persecuted both by a Zoroastrian and a Christian monarchy preceded the spread of Manichaean ideas far and wide. Their adherents found refuge in central Asia and China, where Manichaeism appears to have flourished as late as the thirteenth century.

As for orthodox Christians in Persia, although a fifth-century peace stipulated that they should enjoy toleration, the danger that they might turn disloyal in the continual wars with Rome made this a dead letter. Only at the end of the century did a Persian king issue an edict of toleration and this was merely to conciliate the Armenians. It did not end the problem; Christians were soon irritated by the vigorous proselytizing of Zoroastrian enthusiasts. Further assurances by Persian kings that Christianity was to be tolerated do not suggest that they were very successful or vigorous in seeing that it was. Perhaps it was impossible against the political background: the exception which proves the rule is provided by the Nestorians, who

were

tolerated by the Sassanids, but this was just because they were persecuted by the Romans. They were, therefore, thought likely to be politically reliable. Though religion and the fact that Sassanid power and civilization reached their peak under Chosroes I in the sixth century both

help to give the rivalry of the empires something of the dimensions of a contest between civilizations, the renewed wars of that century are not very interesting. They offer for the most part a dull, ding-dong story, though they were the last round but one of the struggle of East and West begun by the Greeks and Persians a thousand years earlier. The climax to this struggle came at the beginning of the seventh century in the last world war of antiquity. Its devastations may well have been the fatal blow to the Hellenistic urban civilization of the Near East.

Chosroes II, the last great Sassanid, then ruled Persia. His opportunity seemed to have come when a weakened Byzantium – Italy was already gone and the Slavs and Avars were pouring into the Balkans – lost a good emperor, murdered by mutineers. Chosroes owed a debt of gratitude to the dead Maurice, for his own restoration to the Persian throne had been with his aid. He seized on the crime as an excuse and said he would avenge it. His armies poured into the Levant, ravaging the cities of Syria. In 615 they sacked Jerusalem, bearing away the relic of the True Cross which was its most famous treasure. The Jews, it may be remarked, often welcomed the Persians and seized the chance to carry out pogroms of Christians no doubt all the more delectable because the boot had for so long been on the other foot. The next year Persian armies went on to invade Egypt; a year later still, their advance-guards paused only a mile from Constantinople. They even put to sea, raided Cyprus and seized Rhodes from the empire. The empire of Darius seemed to be restored almost at the moment when, at the other end of the Mediterranean, the Roman empire was losing its last possessions in Spain.

This was the blackest moment for Rome in her long struggle with Persia, but a saviour was at hand. In 610 the imperial viceroy of Carthage, Heraclius, had revolted against Maurice’s successor and ended that tyrant’s bloody reign by killing him. In his turn he received the imperial crown from the Patriarch. The disasters in Asia could not at once be stemmed but Heraclius was to prove one of the greatest of the soldier emperors. Only sea-power saved Constantinople in 626, when the Persian army could not be transported to support an attack on the city by their Avar allies. Next year, though, Heraclius broke into Assyria and Mesopotamia, the old disputed heartland of Near Eastern strategy. The Persian army mutinied, Chosroes was murdered and his successor made peace. The great days of Sassanid power were over. The relic of the True Cross – or what was said to be such – was restored to Jerusalem. The long duel of Persia and Rome was at an end and the focus of world history was to shift at last to another conflict.

The Sassanids went under in the end because they had too many enemies.

The year 610 had brought a bad omen: for the first time an Arab force defeated a Persian army. But for centuries Persian kings had been much more preoccupied with enemies on their northern frontiers than with those of the south. They had to contend with the nomads of central Asia who have already made their mark on this narrative, yet the history of these peoples is hard to make out, either as a whole or in detail. None the less, one salient fact is clear – for nearly fifteen centuries central Asia was the source of an impetus in world history which, though spasmodic and confused, produced results ranging from the Germanic invasions of the West to the revitalizing of Chinese government in east Asia.

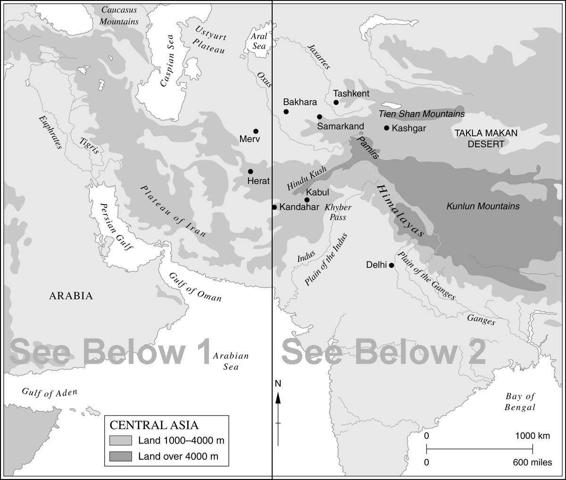

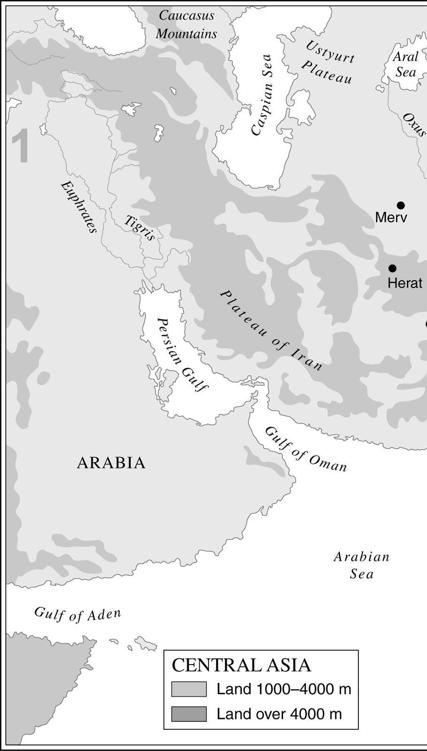

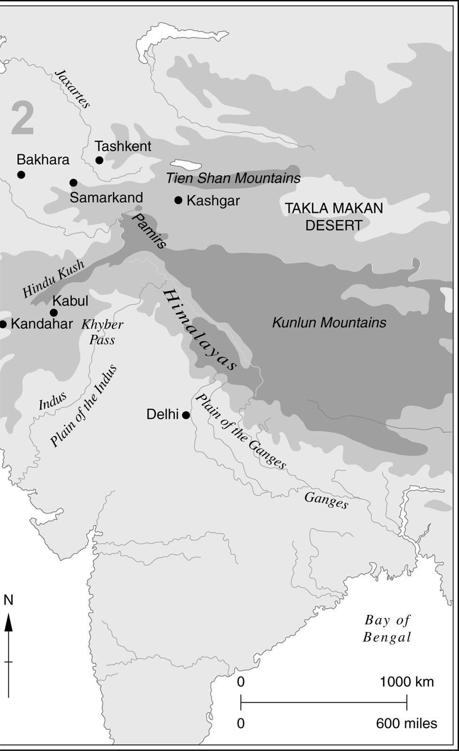

The best starting-point is geography. The place from which the nomads came, ‘central Asia’, is not very well named. The term is imprecise. ‘Landlocked Asia’ might be better, for it is its remoteness from oceanic contact which distinguishes the crucial area. In the first place, this remoteness produced a distinctive and arid climate; secondly, it ensured until modern times an almost complete seclusion from external political pressure, though Buddhism, Christianity and Islam all showed that it was open to cultural influence from the outside. One way to envisage this zone is in a combination of human and topographic terms. It is that part of Asia which is suitable for nomads and it runs like a huge corridor from east to west for 4000 miles or so. Its northern wall is the Siberian forest mass; the southern is provided by deserts, great mountain ranges, and the plateaux of Tibet and Iran. For the most part it is grassy steppe, whose boundary with the desert fluctuates. That desert also shelters important oases, which have always been a distinctive part of its economy. They had settled populations whose way of life both aroused the antagonism and envy of the nomads and also complemented it. The oases were most frequent and richest in the region of the two great rivers known to the Greeks as the Oxus and the Jaxartes. Cities rose there which were famous for their wealth and skills – Bokhara, Samarkand, Merv – and the trade routes which bound distant China to the West passed through them.

No one knows the ultimate origins of the peoples of central Asia. They seem distinctive at the moment they enter history, but more for their culture than for their genetic stock. By the first millennium

BC

they were specialists in the difficult art of living on the move, following pasture with their flocks and herds and mastering the special skills this demanded. It is almost completely true that until modern times they remained illiterate and they lived in a mental world of demons and magic except when converted to the higher religions. They were skilled horsemen and especially adept in the use of the composite bow, the weapon of the mounted archer, which took extra power from its construction not from a single piece of wood

but from strips of wood and horn. They could carry out elaborate weaving, carving and decoration, but of course, did not build, for they lived in their tents.