The New Penguin History of the World (69 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

The appearance of the Venetian challenge and the persistence of old ones would have been embarrassing enough for the Byzantine emperors had they not also faced new trouble at home. In the twelfth century revolt became more common. This was doubly dangerous when the West was entering upon enterprise in the East in the great and complex movement which is famous as the Crusades. The western view of the Crusades need not detain us here; from Byzantium these irruptions from the West looked more and more like new barbarian invasions. In the twelfth century they left behind four crusading states in the former Byzantine Levant as a reminder that there was now another rival in the field in the Near East. When the Muslim forces rallied under Saladin, and there was a resurgence of Bulgarian independence at the end of the twelfth century, the great days of Byzantium were finally over.

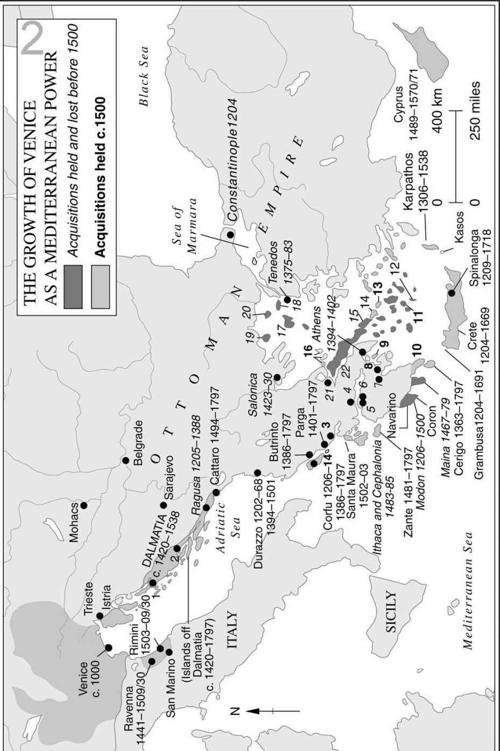

The fatal blow came in 1204, when Constantinople was at last taken and sacked, but by Christians, not the pagans who had threatened it so often. A Christian army which had gone east to fight the infidel in a fourth crusade was turned against the empire by the Venetians. It terrorized and pillaged the city (this was when the bronze horses of the Hippodrome were carried off to stand, as they did until lately, in front of St Mark’s cathedral in Venice), and enthroned a prostitute in the patriarch’s seat in St Sophia. East and West could not have been more brutally distinguished; the sack, denounced by the pope, was to live in Orthodox memory as one of infamy. The ‘Franks’, as the Greeks called them, all too evidently did not see Byzantium as a part of their civilization, nor, perhaps, as even a part of Christendom, for a schism had existed in effect for a century and a half. Though they were to abandon Constantinople and the emperors would be restored in 1261 the Franks would not again be cleared from the old Byzantine territories until a new conqueror came along, the Ottoman Turk. Meanwhile, the heart had gone out of Byzantium, though it had still two centuries in which to die. The immediate beneficiaries were the Venetians and Genoese to whose history the wealth and commerce of Byzantium was now annexed.

The legacy of Byzantium – or a great part of it – was on the other hand already secured to the future, though not, perhaps, in a form in which the eastern Roman would have felt much confidence or pride. It lay in the rooting of Orthodox Christianity among the Slav peoples. This was to have huge consequences, many of which we still live with. The Russian

state and the other modern Slav nations would not have been incorporated into Europe and would not have been reckoned as part of it, if they had not been converted to Christianity in the first place.

Much of the story of how this happened is still obscure, and what is known about the Slavs before Christian times is even more debatable. Though the ground-plan of the Slav peoples of today was established at roughly the same time as that of western Europe, geography makes for confusion. Slav Europe covers a zone where nomadic invasions and the nearness of Asia still left things very fluid long after barbarian society had settled down in the west. Much of the central and south-eastern European landmass is mountainous. There, river valleys channelled the distribution of stocks. Most of modern Poland and European Russia, on the other hand, is a vast plain. Though for a long time covered in forests, it provided neither obvious natural lodgements nor insuperable barriers to settlements. In its huge spaces, rights were disputed for many centuries. By the end of the process, at the beginning of the thirteenth century, there had emerged in the East a number of Slav peoples who would have independent historical futures. The pattern thus set has persisted down to our own day.

There had also come into existence a characteristic Slav civilization, though not all Slavs belonged wholly to it and in the end the peoples of Poland and the modern Czech and Slovak republics were to be more closely tied by culture to the West than to the East. The state structures of the Slav world would come and go, but two of them, those evolved by the Polish and Russian nations, proved particularly tenacious and capable of survival in organized form. They would have much to survive, for the Slav world was at times – notably in the thirteenth and twentieth centuries – under pressure as much from the West as from the East. Western aggressiveness is another reason why the Slavs retained a strong identity of their own.

The story of the Slavs has been traced back at least as far as 2000

BC

when this ethnic group appears to have been established in the eastern Carpathians. For two thousand years they spread slowly both west and east, but especially to the east, into modern Russia. From the fifth to the seventh century

AD

Slavs from both the western and eastern groups began to move south into the Balkans. Perhaps their direction reflects the power of the Avars, the Asiatic people who, after the ebbing of the Hun invasions, lay like a great barrier across the Don, Dnieper and Dniester valleys, controlling south Russia as far as the Danube and courted by Byzantine diplomacy.

Throughout their whole history the Slavs have shown remarkable powers of survival. Harried in Russia by Scythians and Goths, in Poland by Avars and Huns, they none the less stuck to their lands and expanded them; they must have been tenacious agriculturists. Their early art shows a willingness to absorb the culture and techniques of others; they learnt from masters whom they outlasted. It was important, therefore, that in the seventh century there stood between them and the dynamic power of Islam a barrier of two peoples, the Khazars and the Bulgars. These strong peoples also helped to channel the gradual movement of Slavs into the Balkans and down to the Aegean. Later it was to run up the Adriatic coast and was to reach Moravia and central Europe, Croatia, Slovenia and Serbia. By the tenth century Slavs must have been numerically dominant throughout the Balkans.

In this process the first Slav state to emerge was Bulgaria, though the Bulgars were not Slavs, but stemmed from tribes left behind by the Huns. Some of them gradually became Slavicized by intermarriage and contact with Slavs; these were the western Bulgars, who were established in the

seventh century on the Danube. They cooperated with the Slav peoples in a series of great raids on Byzantium; in 559 they had penetrated the defences of Constantinople and camped in the suburbs. Like their allies, they were pagans. Byzantium exploited differences between Bulgar tribes and a ruler from one of them was baptized in Constantinople, the Emperor Heraclius standing godfather. He used the Byzantine alliance to drive out the Avars from what was to be Bulgaria. Gradually, the Bulgars were diluted by Slav blood and influence. When a Bulgar state finally appears at the end of the century we can regard it as Slav. In 716 Byzantium recognized its independence; now an alien body existed on territory long taken for granted as part of the empire. Though there were alliances, this was a thorn in the side of Byzantium which helped to cripple her attempts at recovery in the West. At the beginning of the ninth century the Bulgars killed an emperor in battle (and made a cup for their king from his skull); no emperor had died on campaign against the barbarians since 378.

A turning-point – though not the end of conflict – was reached when the Bulgars were converted to Christianity. After a brief period during which, significantly, he dallied with Rome and the possibility of playing it off against Constantinople, another Bulgarian prince accepted baptism in 865. There was opposition among his people, but from this time Bulgaria was Christian. Whatever diplomatic gain Byzantine statesmen may have hoped for, it was far from the end of their Bulgarian problem. None the less, it is a landmark, a momentous step in a great process, the christianizing of the Slav peoples. It was also an indication of how this would happen: from the top downwards, by the conversion of their rulers.

What was at stake was a great prize, the nature of the future Slav civilization. Two great names dominate the beginning of its shaping, those of the brothers St Cyril and St Methodius, priests still held in honour in the Orthodox communion. Cyril had earlier been on a mission to Khazaria and their work must be set in the overall context of the ideological diplomacy of Byzantium; Orthodox missionaries cannot neatly be distinguished from Byzantine diplomatic envoys, and these churchmen would have been hard put to it to recognize such a distinction. But they did much more than convert a dangerous neighbour. Cyril’s name is commemorated still in the name of the Cyrillic alphabet which he devised. It was rapidly diffused through the Slav peoples, soon reaching Russia, and it made possible not only the radiation of Christianity but the crystallization of Slav culture. That culture was potentially open to other influences, for Byzantium was not its only neighbour, but eastern Orthodoxy was in the end the deepest single influence upon it.

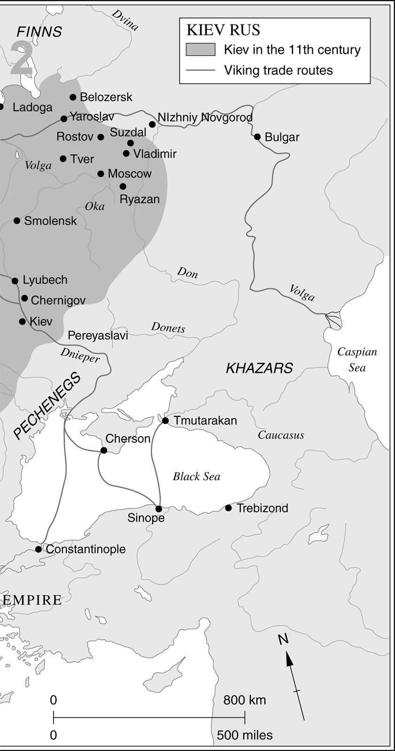

From the Byzantine point of view a still more important conversion was to follow, though not for more than a century. In 860 an expedition with 200 ships raided Byzantium. The citizens were terrified. They listened tremblingly in St Sophia to the prayers of the patriarch: ‘a people has crept down from the north… the people is fierce and has no mercy, its voice is as the roaring sea… a fierce and savage tribe… destroying everything, sparing nothing’. It might have been the voice of a western monk invoking divine protection from the sinister longships of the Vikings, and understandably so, for Viking in essence these raiders were. But they were known to the Byzantines as Rus (or Rhos) and the raid marks the tiny beginnings of Russia’s military power.

As yet, there was hardly anything that could be called a state behind it. Russia was still in the making. Its origins lay in an amalgam to which the Slav contribution was basic. The east Slavs had over the centuries dispersed over much of the upper reaches of the river valleys which flow down to the Black Sea. This was probably because of their primitive agricultural practice of cutting and burning, exhausting the soil in two or three years and then moving on. By the eighth century there were enough of them for there to be signs of relatively dense inhabitation, perhaps of something that could be called town life, on the hills near Kiev. They lived in tribes whose economic and social arrangements remain obscure, but this was the basis of future Russia. We do not know who their native rulers were, but they seem to have lived in the defended stockades which were the first towns, exacting tribute from the surrounding countryside.