The New Penguin History of the World (68 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

Icons had become prominent in eastern churches by the sixth century. There followed two centuries of respect for them and in many places a growing popular devotion to them, but then their use came to be questioned. Interestingly, this happened just after the caliphate had mounted a campaign against the use of images in Islam, but it cannot be inferred that the iconoclasts took their ideas from Muslims. The critics of the icons claimed that they were idols, perverting the worship due to God towards the creations of men. They demanded their destruction or expunging and set to work with a will with whitewash, brush and hammer.

Leo III favoured such men. There is still much that is mysterious about the reason why imperial authority was thrown behind the iconoclasts, but Leo acted on the advice of bishops, and Arab invasions and volcanic eruptions were no doubt held to indicate God’s disfavour. In 730, therefore, an edict forbade the use of images in public worship. A persecution of those who resisted followed; enforcement was always more marked at Constantinople than in the provinces. The movement reached its peak

under Constantine V and was ratified by a council of bishops in 754. Persecution became fiercer, and there were martyrs, particularly among monks, who usually defended icons more vigorously than did the secular clergy. But iconoclasm was always dependent on imperial support; there were ebbings and flowings in the next century. Under Leo IV and Irene, his widow, persecution was relaxed and the ‘iconophiles’ (lovers of icons) recovered ground, though this was followed by renewed persecution. Only in 843, on the first Sunday of Lent, a day still celebrated as a feast of Orthodoxy in the eastern Church, were the icons finally restored.

What was the meaning of this strange episode? There was a practical justification, in that the conversion of Jews and Muslims was said to be made more difficult by Christian respect for images, but this does not take us very far. Once again, a religious dispute cannot be separated from factors external to religion, but the ultimate explanation probably lies in a sense of religious precaution, and given the passion often shown in theological controversy in the eastern empire, it is easy to understand how the debate became embittered. No question of art or artistic merit arose: Byzantium was not like that. What was at stake was the feeling of reformers that the Greeks were falling into idolatry in the extremity of their (relatively recent) devotion to icons and that the Arab disasters were the first rumblings of God’s thunder; a pious king, as in the Israel of the Old Testament, could yet save the people from the consequences of sin by breaking the idols. This was easier in that the process suited the mentalities of a faith which felt itself at bay. It was notable that iconoclasm was particularly strong in the army. Another fact which is suggestive is that icons had often represented local saints and holy men; they were replaced by the uniting, simplifying symbols of eucharist and cross, and this says something about a new, monolithic quality in Byzantine religion and society from the eighth century onwards. Finally, iconoclasm was also in part an angry response to a tide which had long flowed in favour of the monks who gave such prominence to icons in their teaching. As well as a prudent step towards placating an angry God, therefore, iconoclasm represented a reaction of centralized authority, that of emperor and bishops, against local pieties, the independence of cities and monasteries, and the cults of holy men.

Iconoclasm offended many in the western Church but it showed more clearly than anything yet how far Orthodoxy now was from Latin Christianity. The western Church had been moving, too; as Latin culture was taken over by the Germanic peoples, it drifted away in spirit from the churches of the Greek east. The iconoclast synod of bishops had been an affront to the papacy, which had already condemned Leo’s supporters.

Rome viewed with alarm the emperor’s pretensions to act in spiritual matters. Thus iconoclasm drove deeper the division between the two halves of Christendom. Cultural differentiation had now spread very far – not surprisingly when it could take two months by sea to go from Byzantium to Italy – and by land a wedge of Slav peoples soon stood between the two languages.

Contact between East and West could not be altogether extinguished at the official level. But here, too, history created new divisions, notably when the Pope crowned a Frankish king ‘emperor’ in 800. This was a challenge to the Byzantine claim to be the legatee of Rome. Distinctions within the western world did not much matter in Constantinople; the Byzantine officials identified a challenger in the Frankish realm and thereafter indiscriminately called all westerners ‘Franks’, the usage which was to spread as far as China. The two states failed to cooperate against the Arab and offended one another’s susceptibilities. The Roman coronation may itself have been in part a response to the assumption of the title of emperor at Constantinople by a woman, Irene, an unattractive mother who had blinded her own son. But the Frankish title was only briefly recognized in Byzantium; later emperors in the West were regarded there only as kings. Italy divided the two Christian empires, too, for the remaining Byzantine lands there came to be threatened by Frank and Saxon as much as they had ever been by Lombards. In the tenth century the manipulation of the papacy by Saxon emperors made matters worse.

Of course the two Christian worlds could not altogether lose touch. One German emperor of the tenth century had a Byzantine bride and German art of the tenth century was much influenced by Byzantine themes and techniques. But it was just the difference of two cultural worlds that made such contacts fruitful, and as the centuries went by, the difference became more and more palpable. The old aristocratic families of Byzantium were replaced gradually by others drawn from Anatolian and Armenian stocks. Above all, there was the unique splendour and complication of the life of the imperial city itself, where religious and secular worlds seemed completely to interpenetrate one another. The calendar of the Christian year was inseparable from that of the court; together they set the rhythms of an immense theatrical spectacle in which the rituals of both Church and State displayed to the people the majesty of the empire. There was some secular art, but the art constantly before men’s eyes was overwhelmingly religious. Even in the worst times it had a continuing vigour, expressing the greatness and omnipresence of God, whose vice-regent was the emperor. Ritualism sustained the rigid etiquette of the court about which there proliferated the characteristic evils of intrigue and conspiracy. The public

appearance of even the Christian emperor could be like that of the deity in a mystery cult, preceded by the raising of several curtains from behind which he dramatically emerged. This was the apex of an astonishing civilization, which showed half the world for perhaps half a millennium what true empire was. When a mission of pagan Russians came to Byzantium in the tenth century to examine its version of the Christian religion, as they had examined others, they could only report that what they had seen in Hagia Sophia had amazed them. ‘There God dwells among men,’ they said.

What was happening at the base of the empire, on the other hand, is not easy to say. There are strong indications that population fell in the seventh and eighth centuries; this may be connected both with the disruptions of war and with plague. At the same time there was little new building in the provincial cities and the circulation of the coinage diminished. All these things suggest a flagging economy, as does more and more interference with it by the state. Imperial officials sought to ensure that its primary needs would be met by arranging for direct levies of produce, setting up special organs to feed the cities and by organizing artisans and tradesmen bureaucratically in guilds and corporations. Only one city of the empire retained its economic importance throughout, and that was the capital itself, where the spectacle of Byzantium was played out at its height. Trade never dried up altogether in the empire and right down to the twelfth century there was still an important transit commerce in luxury goods from Asia to the West; its position alone guaranteed Byzantium a great commercial role and stimulation for the artisan industries which provided other luxuries to the West. Finally, there is evidence across the whole period of the continuing growth in power and wealth of the great landowners. The peasants were more and more tied to their estates and the later years of the empire see something like the appearance of important local economic units based on the big landholdings.

This economy was able to support both the magnificence of Byzantine civilization at its height and the military effort of recovery under the ninth-century emperors. Two centuries later an unfavourable conjuncture once more overtaxed the empire’s strength and opened a long era of decline. It began with a fresh burst of internal and personal troubles. Two empresses and a number of short-lived emperors of poor quality weakened control at the centre. The rivalries of two important groups within the Byzantine ruling class got out of hand; an aristocratic party at court whose roots lay in the provinces was entangled in struggles with the permanent officials, the higher bureaucracy. In part this reflected also a struggle of a military with an intellectual élite. Unfortunately, the result was that the army and

navy were starved of the funds they needed by the civil servants and were rendered incapable of dealing with new problems.

At one end of the empire these were provided by the last barbarian migrants of the West, the Christian Normans, now moving into south Italy and Sicily. In Asia Minor they arose from Turkish pressure. Already in the eleventh century a Turkish sultanate of Rum was established inside imperial territory (hence its name, for ‘Rum’ signified ‘Rome’), where Abbasid control had slipped into the hands of local chieftains. After a shattering defeat by the Turks at Manzikert in 1071 Asia Minor was virtually lost, and this was a terrible blow to Byzantine fiscal and manpower resources. The caliphates with which the emperors had learnt to live were giving way to fiercer enemies. Within the empire there was a succession of Bulgarian revolts in the eleventh and twelfth centuries and there spread widely in that province the most powerful of the dissenting movements of medieval Orthodoxy, the Bogomil heresy, a popular movement drawing upon hatred of the Greek higher clergy and their Byzantinizing ways.

A new dynasty, the Comneni, once again rallied the empire and managed to hold the line for another century (1081–1185). They pushed back the Normans from Greece and they fought off a new nomadic threat from south Russia, the Pechenegs, but could not crack the Bulgars or win back Asia Minor and had to make important concessions to do what they did. Some concessions were to their own magnates; some were to allies who would in turn prove dangerous.

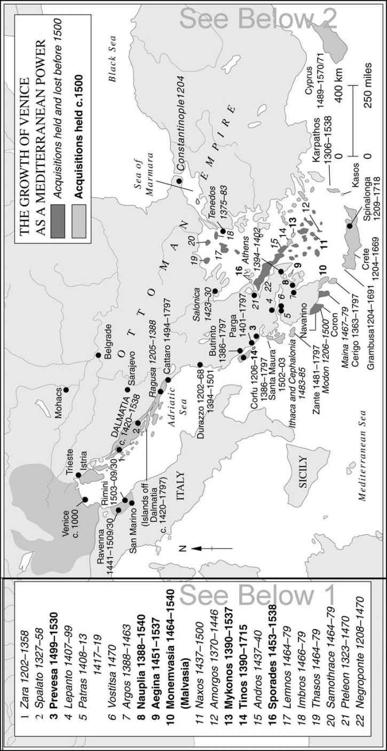

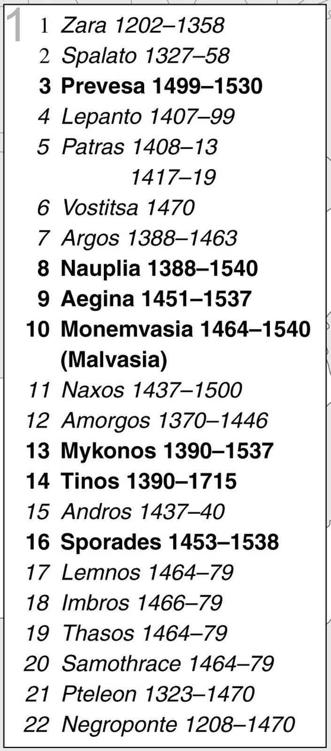

To one of these, the Republic of Venice, once a satellite of Byzantium, concessions were especially ominous, for her whole

raison d’être

had come to be aggrandizement in the eastern Mediterranean. She was the major beneficiary of Europe’s trade with the East and at an early time had developed a specially favoured position. In return for help against the Normans in the eleventh century, the Venetians were given the right to trade freely throughout the empire; they were to be treated as subjects of the emperor, not as foreigners. Venetian naval power grew rapidly and, as the Byzantine fleet fell into decline, it was more and more dominant. In 1123 the Venetians destroyed the Egyptian fleet and thereafter were uncontrollable by their former suzerain. One war was fought with Byzantium, but Venice did better from supporting the empire against the Normans and from the pickings of the Crusades. Upon these successes followed commercial concessions and territorial gains and the former mattered most; Venice, it may be said, was built on the decline of the empire, which was an economic host of huge potential for the Adriatic parasite – in the middle of the twelfth century there were said to be 10,000 Venetians living at Constantinople, so important was their trade there. By 1204 the Cyclades, many of the other Aegean islands, and much of the Black Sea coasts belonged to them: hundreds of communities were to be added to those and Venetianized in the next three centuries. The first commercial and maritime empire since ancient Athens had been created.