The New Penguin History of the World (63 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

The message demanded exclusive service for Allah. Tradition says that Muhammad on one occasion entered the Kaaba’s shrine and struck with his staff all the images of the other deities which his followers were to wash out, sparing only that of the Virgin and Child (he retained the stone itself). His teaching began with the uncompromising preaching of monotheism in a polytheistic religious centre. He went on to define a series of observances necessary to salvation and a social and personal code which often conflicted with current ideas, for example in its attention to the status of the individual believer, whether man, woman or child. It can readily be understood that such teaching was not always welcome. It seemed yet another disruptive and revolutionary influence – as it was – setting its converts against those of their tribe who worshipped the old gods and

would certainly go to hell for it. It might damage the pilgrim business, too (though in the end it improved it, for Muhammad insisted strictly on the value of pilgrimage to so holy a place). Finally, as a social tie it placed blood second to belief; it was the brotherhood of believers which was the source of community, not the kinship group.

It is not surprising that the leaders of his tribe turned on Muhammad. Some of his followers emigrated to Ethiopia, a monotheistic country already penetrated by Christianity. Economic boycott was employed against the recalcitrants who stayed. Muhammad heard that the atmosphere might be more receptive at another oasis about 250 miles further north, Yathrib. Preceded by some two hundred followers, he left Mecca and went there in 622. This

Hegira

, or emigration, was to be the beginning of the Muslim calendar and Yathrib was to change its name, becoming the ‘city of the prophet’, Medina.

It, too, was an area unsettled by economic and social change. Unlike Mecca, though, Medina was not dominated by one powerful tribe, but was a focus of competition for two; moreover, there were other Arabs there who adhered to Judaism. Such divisions favoured Muhammad’s leadership. Converted families gave hospitality to the immigrants. The two groups were to form the future élite of Islam, the ‘Companions of the Prophet’. Muhammad’s pronouncements for them show a new direction in his concerns, that of organizing a community. From the spiritual emphasis of his Mecca revelations he turned to practical, detailed statements about food, drink, marriage, war. The characteristic flavour of Islam, a religion which was also a civilization and a community, was now being formed.

Medina was the base for subduing first Mecca and then the remaining tribes of Arabia. A unifying principle was available in Muhammad’s idea of the

umma

, the brotherhood of believers. It integrated Arabs (and, at first, Jews) in a society which maintained much of the traditional tribal framework, stressing the patriarchal structure in so far as it did not conflict with the new brotherhood of Islam, even retaining the traditional primacy of Mecca as a place of pilgrimage. Beyond this it is not clear how far Muhammad wished to go. He had made approaches to Jewish tribesmen at Medina, but they had refused to accept his claims; they were therefore driven out, and a Muslim community alone remained, but this need not have implied any enduring conflict with either Judaism or its continuator, Christianity. Doctrinal ties existed in their monotheism and their scriptures even if Christians were believed to fall into polytheism with the idea of the Trinity. Nevertheless, Muhammad enjoined the conversion of the infidel and for those who wished there was a justification here for proselytizing.

Muhammad died in 632. At that moment the community he had created was in grave danger of division and disintegration. Yet on it two Arab empires were to be built, dominating successive historical periods from two different centres of gravity. In each the key institution was the caliphate, the inheritance of Muhammad’s authority as the head of a community, both its teacher and ruler. From the start, there was no tension of religious and secular authority in Islam, no ‘Church and State’ dualism such as was to shape Christian policies for a thousand years and more. Muhammad, it has been well said, was his own Constantine – prophet and sovereign in one. His successors would not prophesy as he had done, but they were long to enjoy his legacy of unity in government and religion.

The first ‘patriarchal’ caliphs were all Quraysh, most of them related to the Prophet by blood or marriage. Soon, they were criticized for their wealth and status and were alleged to act as tyrants and exploiters. The last of them was deposed and killed in 661 after a series of wars in which conservatives contested what they saw as the deterioration of the caliphate from a religious to a secular office. The year 661 saw the beginning of the Umayyad caliphate, the first of the two major chronological divisions of Arab empire, focused on Syria, with its capital as Damascus. It did not bring struggle within the Arab world to an end for in 750 the Abbasid caliphate displaced it. The new caliphate lasted longer. After moving to a new location, Baghdad, it would survive nearly two centuries (until 946)

as a real power and even longer as a puppet regime. Between them the two dynasties gave the Arab peoples three centuries of ascendancy in the Near East.

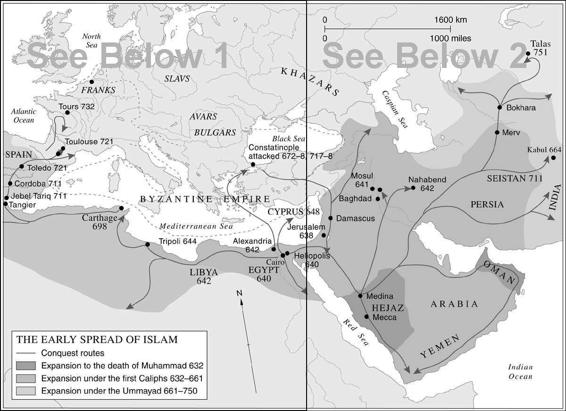

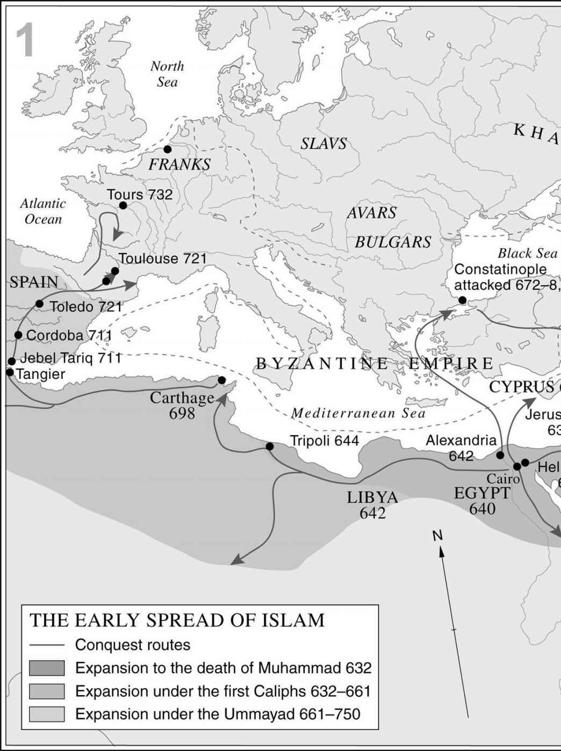

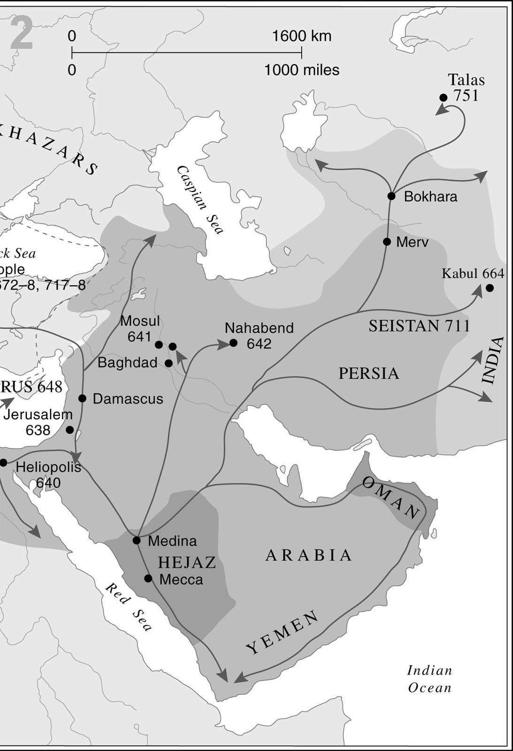

The first and most obvious expression of this was an astonishing series of conquests in the first century of Islam which remade the world map from Gibraltar to the Indus. They had in fact begun immediately after the Prophet’s death with the assertion of the first caliph’s authority. Abu-Bakr set about conquering the unreconciled tribes of southern and eastern Arabia for Islam. But this led to fighting which spread to Syria and Iraq. Something analogous to the processes by which barbarian disturbances in central Asia rolled outward in their effects was at work in the over-populated Arabian peninsula; this time there was a creed to give it direction as well as a simple love of plunder.

Once beyond the peninsula, the first victim of Islam was Sassanid Persia. The challenge came just as she was under strain at the hands of the Heraclian emperors, who were likewise to suffer from this new scourge. In 633 Arab armies invaded Syria and Iraq. Three years later the Byzantine forces were driven from Syria and in 638 Jerusalem fell to Islam. Mesopotamia was wrested from the Sassanids in the next couple of years, and at about the same time Egypt was taken from the empire. An Arab fleet was now created and the absorption of North Africa began. Cyprus was raided in the 630s and 640s; later in the century it was divided between the Arabs and the empire. At the end of the century the Arabs took Carthage, too. Meanwhile, after the Sassanids’ disappearance the Arabs had conquered Khurasan in 655, Kabul in 664; at the beginning of the eighth century they crossed the Hindu Kush to invade Sind, which they occupied between 708 and 711. In the latter year an Arab army with Berber allies crossed the Straits of Gibraltar (its Berber commander, Tariq, is commemorated in that name, which means

Jebel Tariq

, or mount of Tariq) and advanced into Europe, shattering at last the Visigothic kingdom. Finally, in 732, a hundred years after the death of the Prophet, a Muslim army, deep in France, puzzled by over-extended communications and the approach of winter, turned back near Poitiers. The Franks who faced them and killed their commander claimed a victory; at any rate, it was the high water-mark of Arab conquest, though in the next few years Arab expeditions raided into France as far as the upper Rhône. Whatever brought it to an end (and possibly it was just because the Arabs were not much interested in European conquest, once away from the warm lands of the Mediterranean littoral), the Islamic onslaught in the West remains an astonishing achievement, even if Gibbon’s fanciful vision of Oxford teaching the Koran was never remotely near realization.

The Arab armies were at last stopped in the East, too, although only after two sieges of Constantinople and the confining of the eastern empire to the Balkans and Anatolia. From eastern Asia there is a report that an Arab force reached China in the early years of the eighth century; even if questionable, such a story is evidence of the conquerors’ prestige. What is certain is that the frontier of Islam settled down along the Caucasus mountains and the Oxus after a great Arab defeat at the hands of the Khazars in Azerbaijan, and a victory in 751 over a Chinese army commanded by a Korean general on the river Talas, in the high Pamirs. On all fronts, in western Europe, central Asia, Anatolia and in the Caucasus, the tide of Arab conquest at last came to an end in the middle of the eighth century.

That tide had not flowed without interruption. There had been something of a lull in Arab aggressiveness during the internecine quarrelling just before the establishment of the Umayyad caliphate, and there had been bitter fighting of Muslim against Muslim in the last two decades of the seventh century. But for a long time circumstances favoured the Arabs. Their first great enemies, Byzantium and Persia, had both had heavy commitments on other fronts and had been for centuries one another’s fiercest antagonists. After Persia went under, Byzantium still had to contend with enemies in the west and to the north, fending them off with one hand while grappling with the Arabs with the other. Nowhere did the Arabs face an opponent comparable to the Byzantine empire nearer than China. Because of this, they pressed their conquests to the limit of geographical possibility or attractiveness, and sometimes their defeat showed they had overstretched themselves. Even when they met formidable opponents, though, the Arabs still had great military advantages. Their armies were recruited from hungry fighters to whom the Arabian desert had left small alternative; the spur of over-population was behind them. Their assurance in the Prophet’s teaching that death on the battlefield against the infidel would be followed by certain removal to paradise was a huge moral advantage. They fought their way, too, into lands whose peoples were often already disaffected with their rulers; in Egypt, for example, Byzantine religious orthodoxy had created dissident and alienated minorities. Yet when all such influences have been totted up, the Arab success remains amazing. The fundamental explanation must lie in the movement of large numbers of men by a religious ideal. The Arabs thought they were doing God’s will and creating a new brotherhood in the process; they generated an excitement in themselves like that of later revolutionaries. And conquest was only the beginning of the story of the impact of Islam on the world. In its range and complexity it can only be compared to that of Judaism

or Christianity. At one time it looked as if Islam might be irresistible everywhere. That was not to be, but one of the great traditions of civilization was to be built on its conquests and conversions.

2

The Arab Empires

In 661 the Arab governor of Syria, Mu-Awiyah, set himself up as caliph after a successful rebellion and the murder (though not at his hands) of the caliph Ali, cousin and son-in-law of the Prophet. This ended a period of anarchy and division. It was also the foundation of the Umayyad caliphate.

This usurpation gave political ascendancy among the Arab peoples to the aristocrats of the Quraysh, the very people who had opposed Muhammad at Mecca. Mu-Awiyah set up his capital at Damascus and later named his son crown prince, an innovation which introduced the dynastic principle. This was also the beginning of a schism within Islam, for a dissident group, the Shi’ites, henceforth claimed that the right of interpreting the Koran was confined to Muhammad’s descendants. The murdered caliph, they said, had been divinely designated as

imam

to transmit his office to his descendants and was immune from sin and error. The Umayyad caliphs, correspondingly, had their own party of supporters, called Sunnites, who believed that doctrinal authority changed hands with the caliphate. Together with the creation of a regular army and a system of supporting it by taxation of the unbelievers, a decisive movement was thus made away from an Arab world solely of tribes. The site of the Umayyad capital, too, was important in changing the style of Islamic culture, as were the personal tastes of the first caliph. Syria was a Mediterranean state, but Damascus was roughly on the border between the cultivated land of the Fertile Crescent and the barren expanses of the desert; its life was fed by two worlds. To the desert-dwelling Arabs, the former must have been the more striking. Syria had a long Hellenistic past and both the caliph’s wife and his doctor were Christians. While the barbarians of the West looked to Rome, Arabs were to be shaped by the heritage of Greece.