The New Penguin History of the World (62 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

The first among these peoples who require mention are the Scythians, though it is not easy to say very precisely who they were. Some, indeed, regard the term as a catch-all, covering several peoples. ‘Scythians’ have been identified by archaeologists in many parts of Asia and Russia, and as far into Europe as Hungary. They seem to have had a long history of involvement in the affairs of the Near East. Some of them are reported harrying the Assyrian borders in the eighth century

BC

. Later they attracted the attention of Herodotus, who had much to say about a people who fascinated the Greeks. Possibly they were never really one people, but a group of related tribes. Some of them seem to have settled in south Russia long enough to build up regular relations with the Greeks as farmers, exchanging grain for the beautiful gold objects made by the Greeks of the Black Sea coasts, which have been found in Scythian graves. But they also most impressed the Greeks as warriors, fighting in the way which was to be characteristic of the Asian nomads, using bow and arrow from horseback, falling back when faced with a superior force. They harassed the Achaemenids and their successors for centuries and shortly before 100

BC

overran Parthia.

The Scythians can serve as an example of the way in which such peoples are set in motion, for they were responding to very distant impulses. They moved because other peoples were moving them. The balance of life in central Asia was always a nice one; even a small displacement of power or resources could deprive a people of its living-space and force it to long treks in search of a new livelihood. Nomads could not travel fast with flocks and herds, but seen from a background of long immunity their irruptions into settled land could seem dramatically sudden. Through large-scale periodic upheavals by such peoples, rather than the more or less continuous frontier raiding and pillaging, central Asia has made its impact on world history.

In the third century

BC

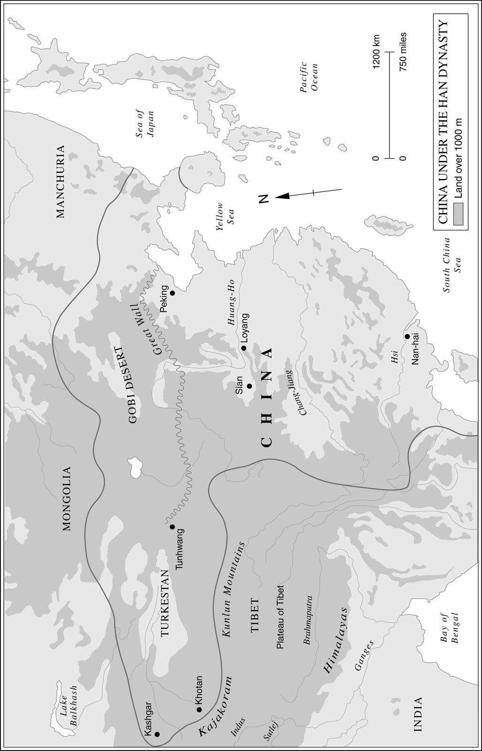

another nomadic people was at the height of its power in Mongolia, the Hsiung-Nu, in whom some recognize the first appearance on the historical stage of those later familiar as Huns. For centuries they were a byword; all sources agree at least that they were most unpleasant opponents, ferocious, cruel and, unfortunately, skilled warriors. It was against them that the Chinese emperors built the Great Wall, a 1400-mile-long insurance policy. Later Chinese governments none the less found it inadequate protection and suffered at the Huns’ hands until they embarked on a forward policy, penetrating Asia so as to outflank the Hsiung-Nu. This led to a Chinese occupation of the Tarim basin up to the foothills of the Pamirs and the building on its north side of a remarkable series of frontier works. It was an early example of the generation of imperialism by suction; great powers can be drawn into areas of no concern to them except as sources of trouble. Whether or not this Chinese advance was the primary cause, the Hsiung-Nu now turned on their fellow nomads and began to push west. This drove before them another people, the Yueh-chih, who in turn pushed out of their way more Scyths. At the end of the line stood the post-Seleucid Greek state of Bactria; it disappeared towards 140

BC

and the Scythians then went on to invade Parthia.

They also pushed into south Russia, and into India, but that part of the story may be set aside for a moment. The history of the central Asian peoples quickly takes the non-specialist out of his depth; experts are in much disagreement, but it is clear that there was no comparable major upheaval such as that of the third century

BC

for another four hundred years or so. Then about

AD

350 came the re-emergence of the Hsiung-Nu in history when Huns began to invade the Sassanid empire (where they were known as Chionites). In the north, Huns had been moving westwards from Lake Baikal for centuries, driven before more successful rivals as others had been driven before them. Some were to appear west of the Volga in the next century; we have already met them near Troyes in 451. Those who turned south were a new handicap to Persia in its struggle with Rome.

Only one more major people from Asia remains to be introduced, the Turks. Again, the first impact on the outside world was indirect. The eventual successors of the Hsiung-Nu in Mongolia had been a tribe called the Juan-Juan. In the sixth century its survivors were as far west as Hungary, where they were called Avars; they are noteworthy for introducing a revolution in cavalry warfare to Europe by introducing there the stirrup, which had given them an important advantage. But they were only in Europe because in about 550 they had been displaced in Mongolia by the Turks, a clan of iron-workers who had been their slaves. Among them were tribes – Khazars, Pechenegs, Cumans – which played important parts in the later history of the Near East and Russia. The Khazars were Byzantium’s allies against Persia, when the Avars were allies of the Sassanids. What has been called the first Turkish empire seems to have been a loose dynastic connection of such tribes running from the Tamir river to the Oxus. A Turkish khan sent emissaries to Byzantium in 568, roughly nine centuries before other Turks were to enter Constantinople in triumph. In the seventh century the Turks accepted the nominal suzerainty of the Chinese emperors, but by then a new element had entered Near Eastern history, for in 637 Arab armies overran Mesopotamia.

This follow-up to the blows of Heraclius announced the end of an era in Persian history. In 620 Sassanid rule stretched from Cyrenaica to Afghanistan and beyond; thirty years later it no longer existed. The Sassanid empire was gone, its last king murdered by his subjects in 651. More than a dynasty passed away, for the Zoroastrian state went down before a new religion as well as before the Arab armies and it was one in whose name the Arabs would go on to yet greater triumphs.

Islam has shown greater expansive and adaptive power than any other religion except Christianity. It has appealed to peoples as different and as distant from one another as Nigerians and Indonesians; even in its heartland, the lands of Arabic civilization between the Nile and India, it encompasses huge differences of culture and climate. Yet none of the other great shaping factors of world history was based on fewer initial resources, except perhaps the Jewish religion. Perhaps significantly, the Jews’ own nomadic origins lay in the same sort of tribal society, barbaric, raw and backward, which supplied the first armies of Islam. The comparison inevitably suggests itself for another reason, for Judaism, Christianity and Islam are the great monotheistic religions. None of them, in their earliest stages, could have been predicted to be world-historical forces, except perhaps by their most obsessed and fanatical adherents.

The history of Islam begins with Muhammad, but not with his birth, for its date is one of many things which are not known about him. His

earliest Arabic biographer did not write until a century or so after he died and even his account survives only indirectly. What is known is that around 570 Muhammad was born in the Hejaz of poor parents, and was soon an orphan. He emerges as an individual in young manhood preaching the message that there is one God, that He is just and will judge all men, who may assure their salvation by following His will in their religious observance and their personal and social behaviour. This God had been preached before, for he was the God of Abraham and the Jewish prophets, of whom the last had been Jesus of Nazareth.

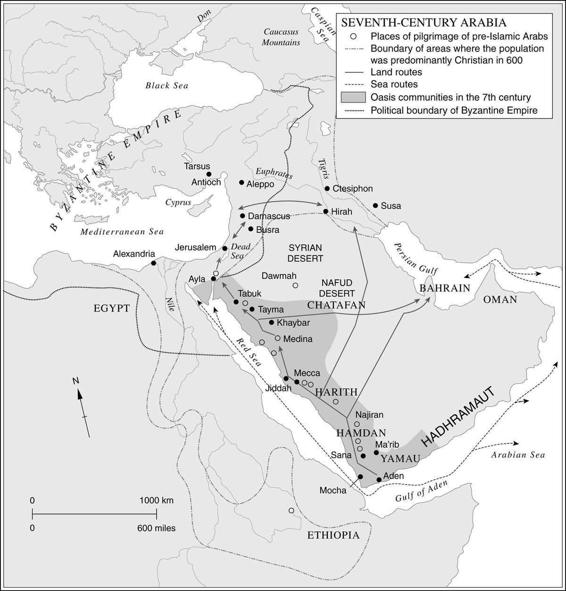

Muhammad belonged to a minor clan of an important Bedouin tribe, the Quraysh. It was one of many in the huge Arabian peninsula, an area 600 miles wide and over a thousand long. Those who lived there were subjected to very testing physical conditions; scorched in its hot season, most of Arabia was desert or rocky mountain. In much of it even survival was an achievement. But around its fringes there were little ports, the homes of Arabs who had been seafarers long before, in the second millennium

BC

. Their enterprise linked the Indus valley to Mesopotamia and brought the spices and gums of east Africa up the Red Sea to Egypt. The origins of these peoples and those who lived inland is disputed, but both language and the traditional genealogies which go back to Old Testament patriarchs suggest ties with other early Semitic pastoralists who were also ancestors of the Jews, however disagreeable such a conclusion may be to some today.

Arabia had not always been so uninviting. Just before and during the first centuries of the Christian era it contained a group of prosperous kingdoms. They survived until, possibly, the fifth century

AD

; both Islamic tradition and modern scholarship link their disappearance with the collapse of the irrigation arrangements of south Arabia. This produced migration from south to north, which created the Arabia of Muhammad’s day. None of the great empires had penetrated more than briefly and fairly superficially into the peninsula, and Arabia had undergone little sophisticating fertilization from higher civilizations. It declined swiftly into a tribal society based on nomadic pastoralism. To regulate its affairs, patriarchy and kinship was enough so long as the Bedouin remained in the desert.

At the end of the sixth century new changes can be detected. At some oases, population was growing. There was no outlet for it and this was straining traditional social practice. Mecca, where the young Muhammad lived, was such a place. It was important both as an oasis and as a pilgrim centre, for people came to it from all over Arabia to venerate a black meteoric stone, the Kaaba, which had for centuries been important in Arab religion. But Mecca was also an important junction of caravan routes between the Yemen and Mediterranean ports. Along them came foreigners and strangers. The Arabs were polytheists, believing in nature gods, demons and spirits, but as intercourse with the outside world increased, Jewish and Christian communities appeared in the area; there were Christian Arabs before there were Muslims.

At Mecca some of the Quraysh began to go in for commerce (another of the few early biographical facts we know about Muhammad is that in his twenties he was married to a wealthy Qurayshi widow who had money in the caravan business). But such developments brought further social strains as the unquestioned loyalties of tribal structure were compromised by commercial values. The social relationships of a pastoral society had always assumed noble blood and age to be the accepted concomitants of wealth and this was no longer always the case. Here were some of the

formative psychological pressures working on the tormented young Muhammad. He began to ponder the ways of God to man. In the end he articulated a system which helpfully resolved many of the conflicts arising in his disturbed society.

The roots of his achievement lay in the observation of the contrast between the Jews and Christians who worshipped the God familiar also to his own people as Allah, and the Arabs; Christians and Jews had a scripture for reassurance and guidance, and Muhammad’s people had none. One day while he contemplated in a cave outside Mecca a voice came to him revealing his task:

Recite, in the name of the Lord, who created, Created man from a clot of blood.

For twenty-two years Muhammad was to recite and the result is one of the great formative books of mankind, the Koran. Its narrowest significance is still enormous and, like that of Luther’s Bible or the Authorized Version, it is linguistic; the Koran crystallized a language. It was the crucial document of Arabic culture not only because of its content but because it was to propagate the Arabic tongue in a written form. But it is much more: it is a visionary’s book, passionate in its conviction of divine inspiration; vividly conveying Muhammad’s spiritual genius and vigour. Though not collected in his lifetime, it was taken down by his entourage as delivered by him in a series of revelations; Muhammad saw himself as a passive instrument, a mouthpiece of God. The word

Islam

means submission or surrender. Muhammad believed he was to convey God’s message to the Arabs as other messengers had earlier brought His word to other peoples. But Muhammad was sure that his position was special; though there had been prophets before him, their revelations heard (but falsified) by Jew and Christian, he was the final Prophet. Through him, Muslims were to believe, God spoke his last message to mankind.