The New Penguin History of the World (64 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

The first Umayyad speedily reconquered the East from dissidents who resisted the new regime and the Shi’ite movement was driven underground. There followed a glorious century whose peak came under the sixth and seventh caliphs between 685 and 705. Unfortunately we know little about

the detailed and institutional history of Umayyad times. Archaeology sometimes throws light on general trends and reveals something of the Arabs’ impact on their neighbours. Foreign records and Arab chroniclers log important events. Nevertheless, early Arab history produces virtually no archive material apart from an occasional document quoted by an Arab author. Nor did Islamic religion have a bureaucratic centre of ecclesiastical government. Islam had nothing remotely approaching the records of the papacy in scope, for example, though the analogy between the popes and the caliphs might reasonably arouse similar expectations. Instead of administrative records throwing light on continuities there are only occasional collections preserved almost by chance, such as a mass of papyri from Egypt, special accumulations of documents by minority communities such as the Jews, and coins and inscriptions. The huge body of Arabic literature in print or manuscript provides further details, but it is at present much more difficult to make general statements about the government of the caliphates with confidence than, say, similar statements about Byzantium.

It seems, none the less, that the early arrangements of the caliphates, inherited from the orthodox caliphs, were loose and simple – perhaps too loose, as the Umayyad defection showed. Their basis was conquest for tribute, not for assimilation, and the result was a series of compromises with existing structures. Administratively and politically, the early caliphs took over the ways of earlier rulers. Byzantine and Sassanid arrangements continued to operate; Greek was the language of government in Damascus, Persian in Ctesiphon, the old Sassanid capital, until the early eighth century. Institutionally, the Arabs left the societies they took over by and large undisturbed except by taxation. Of course, this does not mean that they went on just as before. In north-western Persia, for example, Arab conquest seems to have been followed by a decline in commerce and a drop in population, and it is hard not to associate this with the collapse of a complex drainage and irrigation system successfully maintained in Sassanid times. In other places, Arab conquest had less drastic effects. The conquered were not antagonized by having to accept Islam, but took their places in a hierarchy presided over by the Arab Muslims. Below them came the converted neo-Muslims of the tributary peoples, then the

dhimmi

, or ‘protected persons’ as the Jewish and Christian monotheists were called. Lowest down the scale came unconverted pagans or adherents of no revealed religion. In the early days, the Arabs were segregated from the native population and lived as a military caste in special towns, paid by the taxes raised locally, forbidden to enter commerce or own land.

This could not be kept up. Like the Bedouin customs brought from the desert, segregation was eroded by garrison life. Gradually the Arabs became

landowners and cultivators, and so their camps changed into new, cosmopolitan cities such as Kufa or Basra, the great entrepôt of the trade with India. More and more Arabs mixed with the local inhabitants in a two-way relationship, as the indigenous élites underwent an administrative and linguistic arabization. The caliphs appointed more and more of the officials of the provinces and by the mid-eighth century Arabic was almost everywhere the language of government. Together with the standard coinage bearing Arabic inscriptions it is the major evidence of Umayyad success in laying the foundations of a new, eclectic civilization. Such changes were effected fastest in Iraq, where they were favoured by prosperity as trade revived under the Arab peace.

The assertion of their authority by the Umayyad caliphs was one source of their troubles. Local bigwigs, especially in the eastern half of the empire, resented interference with their practical independence. Whereas many of the aristocracy of the former Byzantine territories emigrated to Constantinople, the élites of Persia could not; they had nowhere to go and had to remain, irritated by their subordination to the Arabs who left them much of their local authority. Nor did it help that the later Umayyad caliphs were men of poor quality, who did not command the respect won by the great men of the dynasty. Civilization softened them. When they sought to relieve the tedium of life in the towns they governed, they moved out into the desert, not to live again the life of the Bedouin, but to enjoy their new towns and palaces, some of them remote and luxurious, equipped as they were with hot baths and great hunting enclosures, and supplied from irrigated plantations and gardens.

There were opportunities here for the disaffected, among whom the

Shi’a

, the party of the Shi’ites, were especially notable. Besides their original political and religious appeal, they increasingly drew on social grievances among the non-Arab converts to Islam, particularly in Iraq. From the start, the Umayyad regime had distinguished sharply between those Muslims who were and those who were not by birth members of an Arab tribe. The numbers of the latter class grew rapidly; the Arabs had not sought to convert (and sometimes even tried to deter from conversion in early times) but the attractiveness of the conquering creed was powerfully reinforced by the fact that adherence to it might bring tax relief. Around the Arab garrisons, Islam had spread rapidly among the non-Arab populations, which grew up to service their needs. It was also very successful among the local élites who maintained the day-to-day administration. Many of these neo-Muslims, the

mawali

, as they were called, eventually became soldiers, too. Yet they increasingly felt alienated and excluded from the aristocratic society of the pure Arabs. The puritanism and orthodoxy of the

Shi’ites, equally alienated from the same society for political and religious reasons, made a great appeal to them.

Increasing trouble in the east heralded the breakdown of Umayyad authority. In 749 a new caliph, Abu-al-Abbas, was hailed publicly in the mosque at Kufa in Iraq. This was the beginning of the end for the Umayyads. The pretender, a descendant of an uncle of the Prophet, announced his intention of restoring the caliphate to orthodox ways; he appealed to a wide spectrum of opposition including the Shi’ites. His full name was promising: it meant ‘Shedder of Blood’. In 750 he defeated and executed the last Umayyad caliph. A dinner-party was held for the males of the defeated house; the guests were murdered before the first course, which was then served to their hosts. With this clearing of the decks began nearly two centuries during which the Abbasid caliphate ruled the Arab world, the first of them the most glorious.

The support the Abbasids enjoyed in the eastern Arab dominions was reflected by the shift of the capital to Iraq, to Baghdad, until then a Christian village on the Tigris. The change had many implications. Hellenistic influences were weakened; Byzantium’s prestige seemed less unquestionable. A new weight was given to Persian influence, which was both politically and culturally to be very important. There was a change in the ruling caste, too, and one sufficiently important to lead some historians to call it a social revolution. They were from this time Arabs only in the sense of being Arabic-speaking; they were no longer Arabian. Within the matrix provided by a single religion and a single language the élites which governed the Abbasid empire came from many peoples right across the Middle East. They were almost always Muslim but they were often converts or children of convert families. The cosmopolitanism of Baghdad reflected the new cultural atmosphere. A huge city, rivalling Constantinople, with perhaps a half-million inhabitants, it was a complete antithesis of the ways of life brought from the desert by the first Arab conquerors. A great empire had come again to the whole Middle East. It did not break with the past ideologically, though, for after dallying with other possibilities the Abbasid caliphs confirmed the Sunnite orthodoxy of their predecessors. This was soon reflected in the disappointment and irritation of the Shi’ites who had helped to bring them to power.

The Abbasids were a violent lot and did not take risks with their success. They quickly and ruthlessly quenched opposition and bridled former allies who might turn sour. Loyalty to the dynasty, rather than the brotherhood of Islam, was increasingly the basis of the empire and this reflected the old Persian tradition. Much was made of religion as a buttress to the dynasty, though, and the Abbasids persecuted nonconformists. The machinery of government became more elaborate. Here one of the major developments was that of the office of vizier (monopolized by one family until the legendary caliph Haroun-al-Raschid wiped them out). The whole structure became somewhat more bureaucratized, the land taxes raising a big revenue to maintain a magnificent monarchy. Nevertheless, provincial distinctions remained very real. Governorships tended to become hereditary, and, because of this, central authority was eventually forced on to the defensive. The governors exercised a greater and greater power in appointments and the handling of taxation. It is not easy to say what was the caliphate’s real power, for it regulated a loose collection of provinces whose actual dependence was related very much to the circumstances of the moment.

But of Abbasid wealth and prosperity at its height there can be no doubt. They rested not only on its great reserves of manpower and the large areas where agriculture was untroubled during the Arab peace, but also upon the favourable conditions it created for trade. A wider range of commodities circulated over a larger area then ever before. This revived commerce in the cities along the caravan routes which passed through the Arab lands from east to west. The riches of Haroun-al-Raschid’s Baghdad reflected the prosperity they brought.

Islamic civilization in the Arab lands reached its peak under the Abbasids. Paradoxically, one reason was the movement of its centre of gravity away from Arabia and the Levant. Islam provided a political organization which, by holding together a huge area, cradled a culture which was essentially synthetic, mingling, before it was done, Hellenistic, Christian, Jewish, Zoroastrian and Hindu ideas. Arabic culture under the Abbasids had closer access to the Persian tradition and a new contact with India which brought to it renewed vigour and new creative elements.

One aspect of Abbasid civilization was a great age of translation into Arabic, the new lingua franca of the Middle East. Christian and Jewish scholars made available to Arab readers the works of Plato and Aristotle, Euclid and Galen, thus importing the categories of Greek thought into Arab culture. The tolerance of Islam for its tributaries made this possible in principle from the moment when Syria and Egypt were conquered, but it was under the early Abbasids that the most important translations were made. So much it is possible to chart fairly confidently. To say what this meant, of course, is more difficult, for though the texts of Plato might be available, it was the Plato of late Hellenistic culture, transmitted through interpretations by Christian monks and Sassanid academics.

The culture these sources influenced was predominantly literary; Arabic Islam produced beautiful buildings, lovely carpets, exquisite ceramics, but its great medium was the word, spoken and written. Even the great Arab scientific works are often huge prose compendia. The accumulated bulk of this literature is immense and much of it simply remains unread by western scholars. Large numbers of its manuscripts have never been examined at all. The prospect is promising; the absence of archive material for early Islam is balanced by a huge corpus of literature of all varieties and forms except the drama. How deeply it penetrated Islamic society remains obscure, though it is clear that educated people expected to be able to write verses and could enjoy critically the performances of singers and bards. Schools were widespread; the Islamic world was probably highly literate by comparison, for example, with medieval Europe. Higher learning, more closely religious in so far as it was institutionalized in the mosques

or special schools of religious teachers, is more difficult to assess. How much, therefore, the potentially divisive and stimulating effect of ideas drawn from other cultures was felt below the level of the leading Islamic thinkers and scientists is hard to say, but potentially many seeds of a questioning and self-critical culture were there from the eighth century onwards. They seem not to have ripened.

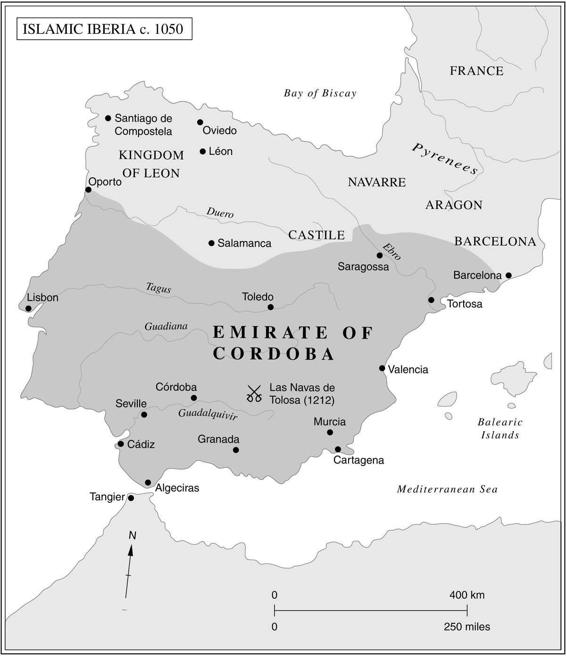

Judged by its greatest men, Arabic culture was at its height in the East in the ninth and tenth centuries and in Spain in the eleventh and twelfth. Although Arab history and geography are both very impressive, its greatest triumphs were scientific and mathematical; we still employ the ‘arabic’ numerals which made possible written calculations with far greater simplicity than did Roman numeration and which were set out by an Arab arithmetician (although in origin they were Indian). This transmission function of Arabic culture was always important and characteristic but must not obscure its originality. The name of the greatest of Islamic astronomers, Al-Khwarizmi, indicates Persian Zoroastrian origins; it expresses the way in which Arabic culture was a confluence of tributaries. His astronomical tables, none the less, were an Arabic achievement, an expression of the synthesis made possible by Arab empire.