The New Penguin History of the World (156 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

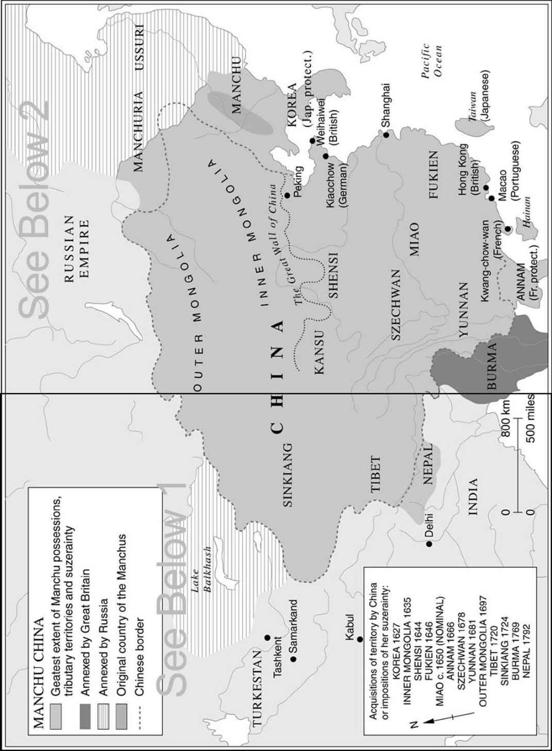

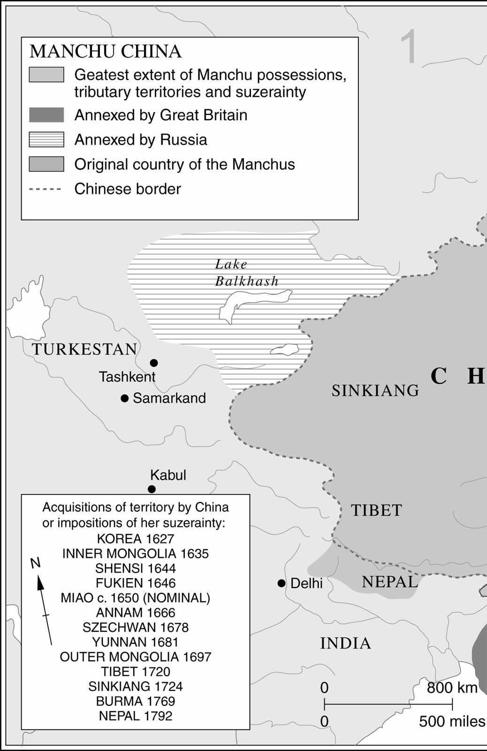

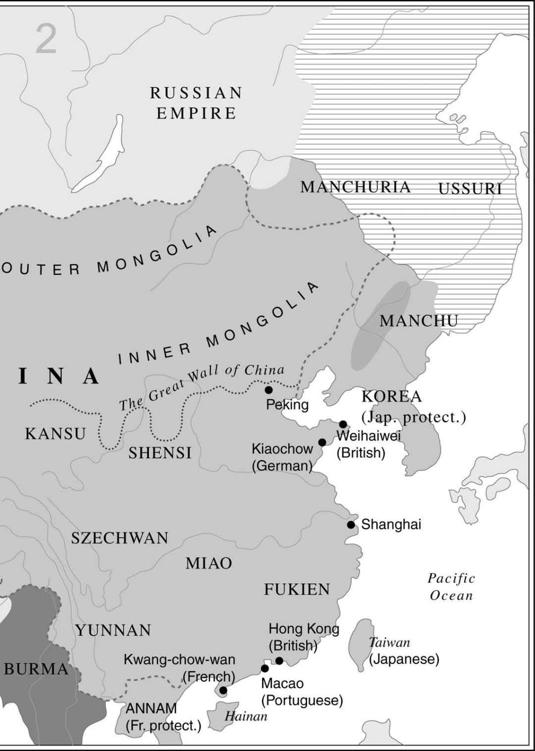

The inflation itself was a result of changing relations with the outside world which within a few decades made nonsense of the reception given to Macartney. Before 1800 the West could offer China little that she wanted except silver, but within the next three decades of the nineteenth century this ceased to be so, largely because British traders at last found a commodity the Chinese wanted and India could supply: opium. Naval expeditions forced the Chinese to open their country to sale (albeit at first under certain restrictions) of this drug, but the ‘Opium War’, which began in 1839, ended in 1842 with a treaty which registered a fundamental change in China’s relations with the West. The Canton monopoly and the tributary status of the foreigner came to an end together. Once the British had kicked ajar the door to western trade, others were to follow them through it.

Unwittingly, the government of Queen Victoria had launched the Chinese Revolution. The 1840s opened a period of upheaval which took over a century to come to completion. The revolution would slowly reveal itself as a double repudiation, both of the foreigner and of much of the Chinese past. The first would increasingly express itself in the nationalist modes and idioms of the progressive European world. Because such ideological forces could not be contained within the traditional framework, they would in the end prove fatal to it, when the Chinese sought to remove the obstacles to modernization and national power. More than a century after the Opium War the Chinese Revolution finally shattered for good a social system which had been the foundation of Chinese life for thousands of years. By that time, though, much of old China would already have vanished. By that time, too, it would appear that China’s troubles had also been a part of an even wider upheaval, a Hundred Years’ War of Asia and the West, whose turning-point came in the early twentieth century.

These implications matured only slowly. In the beginning, western encroachments in China usually produced only a simple, xenophobic hostility and even this was not universal. After all, for a long time very few Chinese were directly or obviously much concerned with the coming of the foreigners. A few (notably Canton merchants involved in the foreign trade) even sought accommodation with them. Hostility was a matter of anti-British mobs in the towns and of the rural gentry. At first many officials saw the problem as a limited one: that of the addiction of the subjects of the empire to a dangerous drug. They were humiliated, in particular, by the weaknesses which this revealed in their own people and administration; there was much connivance and corruption involved in the opium trade. They do not at first seem to have seen the deeper issue of the future, that of the questioning of an entire order, or to have sensed a cultural threat; China had suffered defeats in the past and its culture had survived unscathed.

The first portent of a deeper danger came when, in the 1840s, the imperial government had to concede that missionary activity was legal. Though still limited, this was obviously corrosive of tradition. Officials in the Confucian mould who felt its danger, stirred up popular feeling against missionaries – whose efforts made them easy targets – and there were scores of riots in the 1850s and 1860s. Such demonstrations often made things worse. Sometimes foreign consuls would be drawn in; exceptionally a gunboat would be sent. The Chinese government’s prestige would suffer in the ensuing exchange of apologies and punishment of culprits. Meanwhile,

the activity of the missionaries was steadily undermining the traditional society in more direct and didactic ways by preaching an individualism and egalitarianism alien to it and by acting as a magnet to converts to whom it offered economic and social advantages. The inability of the imperial government to stamp out Christianity was a telling indicator of the limits of its power.

The process of undermining China also went forward directly by military and naval means; there were further impositions of concessions by force. But there was a growing ambiguity in the Chinese response. The authorities did not always resist the arrival of the foreigners. First the gentry of the areas immediately concerned and then the Peking government came round to feeling that foreign soldiers might not be without their value for the regime. Social disorder was growing. It could not be canalized solely against the foreigners and was threatening the establishment; China was beginning to undergo a cycle of peasant revolts which were to be the greatest in the whole of human history. In the middle decades of the century the familiar indicators multiplied: banditry, secret societies. In the 1850s the ‘Red Turbans’ were suppressed only at great cost. Such troubles frightened the establishment, and threw it on to the defensive, leaving it with little spare capacity to resist the steady gnawing of the West. These great rebellions were fundamentally caused by hunger for land, and the most important and distinctive of them was the Taiping rebellion or, as it may more appropriately be called, revolution, which lasted from 1850 to 1864.

The heart of this great convulsion, which cost the lives of more people than died the world over in the First World War, was a traditional peasant revolt. Hard times and a succession of natural disasters had helped to provoke it. It drew on a compound of land hunger, hatred of tax-gatherers, social envy and national resentment against the Manchus (though it is hard to see exactly what this meant in practice, for most of the officials who actually administered the empire were, of course, themselves Chinese). It was also a regional outbreak, originating in the south and even there promoted by an isolated minority of settlers from the north. The new feature behind the revolt, and one which made it ambiguous in the eyes of both Chinese and Europeans, was that its leader, Hung Hsiu-ch’uan, had a superficial but impressive acquaintance with the Christian religion in the form of American Protestantism. This led him not only to rewrite the Decalogue with a new emphasis on filial piety, but, among other things, to denounce the worship of other gods and destroy idols and to talk of establishing the kingdom of God on earth. He felt rejected by his own culture, for he had been unsuccessful in the examinations which conferred status on low-born Chinese. Within the familiar framework of one of the

periodic peasant upheavals of old China, that is to say, a new ideology was at work and showing itself subversive of the traditional culture and state. Some of its opponents at once grasped this and saw the movement as an ideological as well as a social challenge. Thus the Taiping rebellion can be seen as an epoch in the western disruption of China.

The Taiping army at first had a series of spectacular successes. By 1853 they had captured Nanking and established there the court of Hung Hsiu-ch’uan, now proclaimed the ‘Heavenly King’. In spite of alarm further north, though, this was as far as they went. After 1856 the revolution was on the defensive. Nevertheless, it announced important social changes (which were to be praised later by Chinese communists) and although it is by no means clear how widely these were effective or even appealing, they had real disruptive ideological effects. The basis of Taiping social doctrine was not private property but communal provision for general needs. The land was in theory distributed for working in plots graded by quality to provide just shares. Even more revolutionary was the proclaimed extension of social and educational equality to women. The traditional binding of their feet was forbidden and a measure of sexual austerity marked the movement’s aspirations (though not the conduct of the ‘Heavenly King’ himself). All this reflected the mixture of religious and social elements which lay at the root of the Taiping cult and threatened the traditional order.

The movement benefited at first from the demoralization brought about in the Manchu forces by their defeats at the hands of the Europeans and from the usual weaknesses shown by central government in China in a region relatively remote and distinct. As time passed and the Manchu forces were given abler (sometimes European) commanders, the bows and spears of the Taipings proved insufficient. The foreigners, too, came to see the movement as a threat but kept up their pressure on the imperial government while it grappled with the Taipings. Treaties with France and the United States, which followed that with Great Britain, guaranteed the toleration of Christian missionaries and began the process of reserving jurisdiction over foreigners to consular and mixed courts. The danger from the Taiping brought yet more concessions: the opening of more Chinese ports to foreign trade, the introduction to the Chinese customs administration of foreign superiors, the legalization of the sale of opium and the cession to the Russians of the province in which Vladivostok was to be built. It is hardly surprising that in 1861 the Chinese decided for the first time to set up a new department to deal with foreign affairs. The old myth that all the world recognized the ‘Mandate of Heaven’ and owed tribute to the imperial court was dead.

In the end, the foreigners joined in against the Taipings. Whether their help was needed to end it is hard to say; certainly the movement was already failing. In 1864 Hung died and shortly afterwards Nanking fell to the Manchu. This was a victory for traditional China: the rule of the bureaucratic gentry had survived one more threat from below. None the less, an important turning-point had been reached. A rebellion had offered a revolutionary programme announcing a new danger, that the old challenge of peasant rebellion might be reinforced by an ideology from outside deeply corrosive to Confucian China. Nor did the end of the Taiping rebellion mean internal peace; from the middle of the 1850s until well into the 1870s there were great Muslim risings in the north-west and south-west as well as other rebellions.

Immediately, China showed even greater weakness in the face of the western barbarians. Large areas had been devastated in the fighting; in many of them the soldiers were powerful and threatened the control of the bureaucracy. If the enormous loss of life did something to reduce pressure on land, this was probably balanced by a decline in the prestige and authority of the dynasty. Concessions had already had to be made to the Western powers under and because of these disadvantaged conditions; between 1856 and 1860 British and French forces were engaged every year against the Chinese. A treaty in 1861 brought to nineteen the number of ‘treaty ports’ open to western merchants and provided for a permanent British ambassador at Peking. Meanwhile, the Russians exploited the Anglo-French successes to secure the opening of their entire border with China to trade. Further concessions would follow. It was evident that methods which had drawn the sting of nomadic invaders were not likely to work with confident Europeans, whose ideological assurance and increasing technical superiority protected them from the seduction of Chinese civilization. When Roman Catholic missionaries were given the right to buy land and put up buildings Christianity was linked to economic penetration; soon the wish to protect converts meant involvement in the internal affairs of public order and police. It was impossible to contain the slow but continuous erosion of Chinese sovereignty. Never formally a colony, China was beginning none the less to undergo a measure of colonization.