The New Penguin History of the World (49 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

In part this was the simple expression of the social realities on which

the empire rested; Rome, like all the ancient world, was built on a sharp division of rich and poor, and in the capital itself this division was an abyss not concealed but consciously expressed. The contrasts of wealth were flagrant in the difference between the sumptuousness of the houses of the new rich, drawing to themselves the profits of empire and calling on the services of perhaps scores of slaves on the spot and hundreds on the estates which maintained them, and the swarming tenements in which the Roman proletariat lived. Romans found no difficulty in accepting such divisions as part of the natural order; for that matter, few civilizations have ever much worried about them before our own, though few displayed them so flagrantly as imperial Rome. Unfortunately, though easy to recognize, the realities of wealth in Rome still remain curiously opaque to the historian. The finances of only one senator, the younger Pliny, are known to us in any detail.

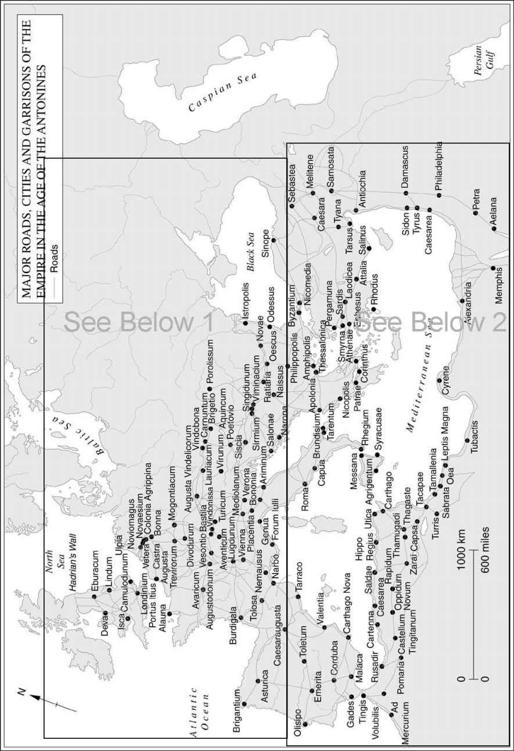

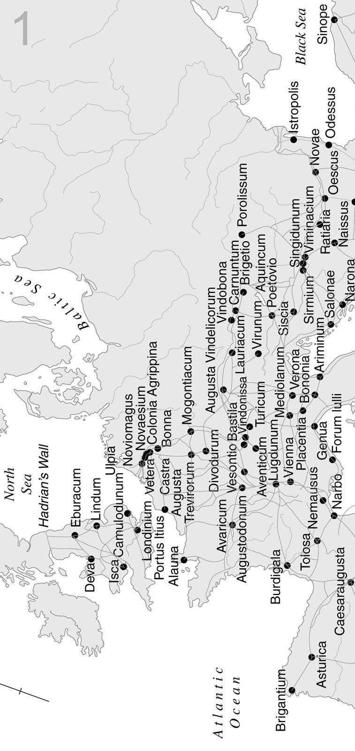

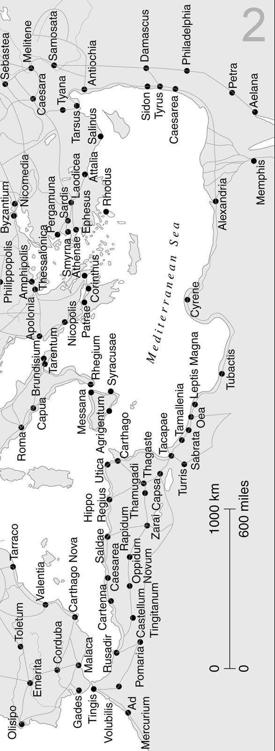

The Roman pattern was reflected in all the great cities of the empire. It was central to the civilization that Rome sustained everywhere. The provincial cities stood like islands of Graeco-Roman culture in the aboriginal countrysides of the subject-peoples. Due allowance made for climate, they reflected a pattern of life of remarkable uniformity, displaying Roman priorities. Each had a forum, temples, a theatre, baths, whether added to old cities, or built as part of the basic plan of those which were refounded. Regular grid-patterns were adopted as ground plans. The government of the cities was in the hands of local bigwigs, the

curiales

or city-fathers who at least until Trajan’s time enjoyed a very large measure of independence in the conduct of municipal affairs, though later a tighter supervision was to be imposed on them. Some of these cities, such as Alexandria or Antioch, or Carthage (which the Romans refounded), grew to a very large size. The greatest of all cities was Rome itself, eventually containing more than a million people.

In this civilization the omnipresence of the amphitheatre is a standing reminder of the brutality and coarseness of which it was capable. It is important not to get this out of perspective, just as it is important not to infer too much about ‘decadence’ from the much-quoted works of would-be moral reformers. One disadvantage under which the repute of Roman civilization has laboured is that it is one of the few before modern times in which we have very much insight into the popular mind through its entertainments, for the gladiatorial games and the wild-beast shows were emphatically mass entertainment in a way in which the Greek theatre was not. Popular relaxation is in any era hardly likely to be found edifying by the sensitive, and the Romans institutionalized its least attractive aspects by building great centres for their shows, and by permitting the massentertainment industry to be used as a political device; the provision of spectacular games was one of the ways in which a rich man could bring to bear his wealth to secure political advancement. Nevertheless, when all allowances are made for the fact that we cannot know how, say, the ancient masses of Egypt or Assyria amused themselves, we are left with the uniqueness of the gladiatorial spectacle; it was an exploitation of cruelty as entertainment on a bigger scale than ever before and one unrivalled until the twentieth century. It was made possible by the urbanization of Roman culture, which could deliver larger mass audiences than ever. The ultimate roots of the ‘games’ were Etruscan, but their development sprang from a new scale of urbanism and the exigencies of Roman politics.

Another aspect of the brutality at the heart of Roman society was, of course, far from unique: the omnipresence of slavery. As in Greek society, slavery was so varied in its forms that it cannot be summarized in a generalization. Many slaves earned wages, some bought their freedom and the Roman slave had rights at law. The growth of large plantation estates, it is true, provided examples of a new intensification of it in the first century or so, but it would be hard to say Roman slavery was worse than that of other ancient societies. A few who questioned the institution were very untypical: moralists reconciled themselves to slave-owning as easily as later Christians were to do.

Much of what we know about popular mentality before modern times is known through religion. Roman religion was a very obvious part of Roman life, but that may be misleading if we think in modern terms. It had nothing to do with individual salvation and not much with individual behaviour; it was above all a public matter. It was a part of the

res publica

, a series of rituals whose maintenance was good for the state, whose neglect would bring retribution. There was no priestly caste set apart from other men (if we exclude one or two antiquarian survivals in the temples of a few special cults) and priestly duties were the task of the magistrates who found priesthood a useful social and political lever. Nor was there creed or dogma. What was required of Romans was only that the ordained services and rituals should be carried out in the accustomed way; for the proletarian this meant little except that he should not work on a holiday. The civic authorities were everywhere responsible for the rites, as they were responsible for the maintenance of the temples. The proper observances had a powerfully practical purpose: Livy reports a consul saying the gods ‘look kindly on the scrupulous observance of religious rites which has brought our country to its peak’. Men genuinely felt that the peace of Augustus was the

pax deorum

, a divine reward for a proper respect for the gods which Augustus had reasserted. Somewhat more cynically, Cicero

had remarked that the gods were needed to prevent chaos in society. This, if different, was also an expression of the Roman’s practical approach to religion. It was not insincere or disbelieving; the recourse to diviners for the interpretation of omens and the acceptance of the decisions of the augurs about important acts of policy would alone establish that. But it was unmysterious and down-to-earth in its understanding of the official cults.

The content of these was a mixture of Greek mythology and festivals and rites derived from primitive Roman practice and therefore heavily marked by agricultural preoccupations. One which lived to deck itself out in the symbols of another religion was the December Saturnalia, which is with us still as Christmas. But the religion practised by Romans stretched far beyond official rites. The most striking feature of the Roman approach to religion was its eclecticism and cosmopolitanism. There was room in the empire for all manner of belief, provided it did not contravene public order or inhibit adherence to the official observances. For the most part, peasants everywhere pursued the timeless superstitions of their local nature cults, townsmen took up new crazes from time to time, and the educated professed some acceptance of the classical pantheon of Greek gods and led the people in the official observances. Each clan and household, finally, sacrificed to its own god with appropriate special rituals at the great moments of human life: childbirth, marriage, sickness and death. Each household had its shrine, each street-corner its idol.

Under Augustus there was a deliberate attempt to reinvigorate old belief, which had been somewhat eroded by closer acquaintance with the Hellenistic East and about which a few sceptics had shown cynicism even in the second century

BC

. After Augustus, emperors always held the office of chief priest (

pontifex maximus

) and political and religious primacy were thus combined in the same person. This began the increasing importance and definition of the imperial cult itself. It fitted well the Roman’s innate conservatism, his respect for the ways and customs of his ancestors. The imperial cult linked respect for traditional patrons, the placating or invoking of familiar deities and the commemoration of great men and events, to the ideas of divine kingship which came from the East, from Asia. It was there that altars were first raised to Rome or the Senate, and there that they were soon reattributed to the emperor. The cult spread through the whole empire, though it was not until the third century

AD

that the practice was wholly respectable at Rome itself, so strong was republican sentiment. But even there the strains of empire had already favoured a revival of official piety which benefited the imperial cult.

This was not all that came from the East. By the second century, the

distinction of a pure Roman religious tradition from others within the empire is virtually impossible. The Roman pantheon, like the Greek, was absorbed almost indistinguishably into a mass of beliefs and cults, their boundaries blurred and fluid, merging imperceptibly over a scale of experience running from sheer magic to the philosophical monotheism popularized by the stoic philosophies. The intellectual and religious world of the empire was omnivorous, credulous and deeply irrational. It is important here not to be over-impressed by the visible practicality of the Roman mind; practical men are often superstitious. Nor was the Greek heritage understood in an altogether rational way; its philosophers were seen by the first century

BC

as men inspired, holy men whose mystical teaching was the most eagerly studied part of their works, and even Greek civilization had always rested on a broad basis of popular superstition and local cult practice. Tribal gods swarmed throughout the Roman world.

All this boils down to a large measure of practical criticism of the ancient Roman ways. Obviously, they were no longer enough for an urban civilization, however numerically preponderant the peasants on which it rested. Many of the traditional festivals were pastoral or agricultural in origin, but occasionally even the god they invoked was forgotten. City-dwellers gradually came to need more than piety in a more and more puzzling world. Men grasped desperately at anything which could give meaning to the world and some degree of control over it. Old superstitions and new crazes benefited. The evidence can be seen in the appeal of the Egyptian gods, whose cults flooded through the empire as its security made travel and intercourse easier (they were even patronized by an emperor, the Libyan Septimius Severus). A civilized world of greater complexity and unity than any earlier was also one of greater and greater religiosity and a curiousness almost boundless. One of the last great teachers of pagan antiquity, Apollonius of Tyana, was said to have lived and studied with the Brahmans of India. Men were looking about for new saviours long before one was found in the first century

AD

.

Another symptom of eastern influence was the popularization of mysteries, cults which rested upon the communication of special virtues and powers to the initiated by secret rites. The sacrificial cult of Mithras, a minor Zoroastrian deity especially favoured by soldiers, was one of the most famous. Almost all the mysteries register impatience with the constraints of the material world, an ultimate pessimism about it and a preoccupation with (and perhaps a promise of survival after) death. In this lay their power to provide a psychological satisfaction no longer offered by the old gods and never really possessed by the official cult. They drew individuals to them; they had some of the appeal that was later to draw

men to Christianity, which in its earliest days was often seen, significantly, as another mystery.