The New Penguin History of the World (44 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

On the Euphrates, Parthia was eventually to meet a new power from the West. Less remote from it than Parthia, and therefore with less excuse, even the Hellenistic kingdoms had been almost oblivious to the rise of Rome, this new star of the political firmament, and went their way almost without regard for what was happening in the West. The western Greeks, of course, knew more about it, but they long remained preoccupied with the first great threat they had faced, Carthage, a mysterious state which almost may be said to have derived its being from hostility to the Greeks. Founded by Phoenicians somewhere around 800

BC

, perhaps even then to offset Greek commercial competition on the metal routes, Carthage had grown to surpass Tyre and Sidon in wealth and power. But she remained a city-state, using alliance and protection rather than conquests and garrisons, her citizens preferring trade and agriculture to fighting. Unfortunately, the native documentation of Carthage was to perish when, finally, the city was razed to the ground and we know little of its own history.

Yet it was clearly a formidable commercial competitor for the western Greeks. By 480

BC

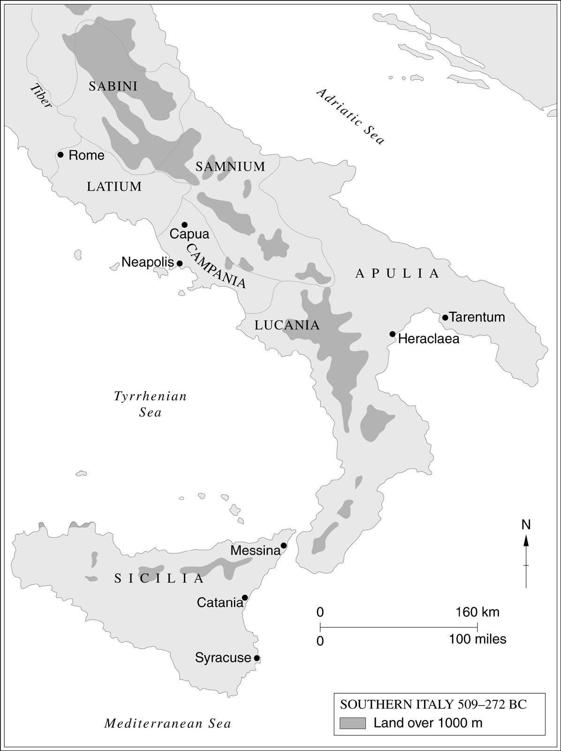

they had been confined commercially to little more than the Rhône valley, Italy and, above all, Sicily. This island, and one of its cities, Syracuse, was the key to the Greek west. Syracuse for the first time protected Sicily from the Carthaginians when she fought and beat them in the year of Salamis. For most of the fifth century Carthage troubled the western Greeks no more and the Syracusans were able to turn to supporting the Greek cities of Italy against the Etruscans. Then Syracuse was the target of the ill-fated Sicilian Expedition from Athens (415–413) because she was the greatest of the western Greek states. The Carthaginians came back after this, but Syracuse survived defeat to enjoy soon afterwards her greatest period of power, exercised not only in the island, but in southern Italy and the Adriatic. During most of it she was at war with Carthage. There was plenty of vigour in Syracuse; at one moment she all but captured Carthage, and another expedition added Corcyra (Corfu) to her Adriatic possessions. But soon after 300

BC

it was clear that Carthaginian

power was growing while Syracuse had also to face a Roman threat in mainland Italy. The Sicilians fell out with a man who might have saved them, Pyrrhus of Epirus, and by mid-century the Romans were masters of the mainland.

There were now three major actors in the arena of the West, yet the Hellenistic east seemed strangely uninterested in what was going forward (though Pyrrhus was aware of it). This was perhaps short-sighted, but at this time the Romans did not see themselves as world conquerors. They were as much moved by fear as by greed in entering on the Punic Wars with Carthage, from which they would emerge victors. Then they would turn east. Some Hellenistic Greeks were beginning to be aware by the end of the century of what might be coming. A ‘cloud in the west’ was one description of the struggle between Carthage and Rome viewed from the Hellenized east. Whatever its outcome, it was bound to have great repercussions for the whole Mediterranean. None the less, the east was to prove in the event that it had its own strengths and powers of resistance. As one Roman later put it, Greece would take her captors captive, Hellenizing yet more barbarians.

5

Rome

All around the western Mediterranean shores and across wide tracts of western Europe, the Balkans and Asia Minor, relics can still be seen of a great achievement, the empire of Rome. In some places – Rome itself, above all – they are very plentiful. To explain why they are there takes up a thousand years of history. If we no longer look back on the Roman achievement as our ancestors often did, feeling dwarfed by it, we can still be puzzled and even amazed that men could do so much. Of course, the closer the scrutiny historians give to those mighty remains, and the more scrupulous their sifting of the documents which explain Roman ideals and Roman practice, the more we realize that Romans were not, after all, superhuman. The grandeur that was Rome sometimes looks more like tinsel and the virtues its publicists proclaimed can sound as much like political cant as do similar slogans of today. Yet when all is said and done, there remains an astonishing and solid core of creativity. In the end, Rome remade the setting of Greek civilization. Thus Romans settled the shape of the first civilization embracing all the West. This was a self-conscious achievement. Romans who looked back on it when it was later crumbling about them still felt themselves to be Romans like those who had built it up. They were, even if only in the sense that they believed it. That was what mattered, though. For all its material impressiveness and occasional grossness, the core of the explanation of the Roman achievement was an idea, the idea of Rome itself, the values it embodied and imposed, the notion of what was one day to be called

romanitas

.

It was believed to have deep roots. Romans said their city was founded by one Romulus in 753

BC

. We need not take this seriously, but the legend of the foster-mother wolf which suckled both Romulus and his twin, Remus, is worth a moment’s pause; it is a good symbol of early Rome’s debt to a past that was dominated by the people called Etruscans, among whose cults has been traced a special reverence for the wolf.

In spite of a rich archaeological record, with many inscriptions and much scholarly effort to make sense of it, the Etruscans remain a mysterious people. All that has so far been delineated with some certainty is the general nature of Etruscan culture, and much less of its history or chronology. Different scholars have argued that Etruscan civilization came into existence at a wide range of different times, stretching from the tenth to the seventh century

BC

. Nor have they been able to agree about where the Etruscans came from; one hypothesis points to immigrants from Asia just after the end of the Hittite empire, but several other possibilities have their

supporters. All that is obvious is that they were not the first Italians. Whenever they came to the peninsula and wherever from, Italy was then already a confusion of peoples.

There were probably still at that time some aboriginal natives among them whose ancestors had been joined by Indo-European invaders in the second millennium

BC

. In the next thousand years some of these Italians developed advanced cultures. Iron-working was going on in about 1000

BC

. The Etruscans probably adopted the skill from the peoples there before them, possibly from a culture which has been called Villanovan (after an archaeological site near modern Bologna). They brought metallurgy to a high level and vigorously exploited the iron deposits of Elba, off the coast of Etruria. With iron weapons, they appear to have established an Etruscan hegemony, which at its greatest extent covered the whole central peninsula, from the valley of the Po down to Campania. Its organization remains obscure, but Etruria was probably a loose league of cities governed by kings. The Etruscans were literate, using an alphabet derived from Greek which may have been acquired from the cities of Magna Graecia (though hardly anything of their writing can be understood), and they were relatively rich.

In the sixth century

BC

the Etruscans were installed in an important bridgehead on the south bank of the river Tiber. This was the site of Rome, one of a number of small cities of the Latins, an old-established people of the Campania. Through this city something of the Etruscan survived to flow into and eventually be lost in the European tradition. Near the end of the sixth century

BC

Rome broke away from Etruscan dominion during a revolt of the Latin cities against their masters. Until then, the city had been ruled by kings, the last of whom, tradition later said, was expelled in 509

BC

. Whatever the exact date, this was certainly about the time at which Etruscan power, over-strained by struggle with the western Greeks, was successfully challenged by the Latin peoples, who thereafter went their own ways. Nevertheless, Rome was to retain much from its Etruscan past. It was through Etruria that Rome first had access to the Greek civilization with which it continued to live in contact both by land and sea. Rome was a focus of important land and water routes, high enough up the Tiber to bridge it, but not so high that the city could not be reached by sea-going vessels. Fertilization by Greek influence was perhaps its most important inheritance, but Rome also preserved much else from its Etruscan past. One was the way its people were organized into ‘centuries’ for military purposes; more superficial but striking instances were its gladiatorial games, civic triumphs and reading of auguries – a consultation of the entrails of sacrifices in order to discern the shape of the future.

The republic was to last for more than 450 years and even after that its institutions survived in name. Romans always harped on continuity and their loyal adherence (or reprehensible non-adherence) to the good old ways of the early republic. This was not just historical invention. There was some reality in such claims, much as there is, for example, in the claims made for the continuity of parliamentary government in Great Britain or for the wisdom of the founding fathers of the United States in agreeing a constitution which still operates successfully. Yet, of course, great changes took place as the centuries passed. They eroded the institutional and ideological continuities and historians still argue about how to interpret them. Yet for all these changes Rome’s institutions made possible a Roman Mediterranean and a Roman empire stretching far beyond it which was to be the cradle of Europe and Christianity. Thus Rome, like Greece (which reached many later men only through Rome), shaped much of the modern world. It is not just in a physical sense that men still live among its ruins.

Broadly speaking, the changes of republican times were symptoms and results of two main processes. One was of decay; gradually the republic’s institutions ceased to work. They could no longer contain political and social realities and in the end this destroyed them, even when they survived in name. The other was the extension of Roman rule first beyond the city and then beyond Italy. For about two centuries both processes went on rather slowly.

Internal politics were rooted in arrangements originally meant to make impossible the return of monarchy. Constitutional theory was concisely expressed in the motto carried by the monuments and standards of Rome until well into imperial times:

SPQR

, the abbreviation of the Latin words for ‘the Roman Senate and People’. Theoretically, ultimate sovereignty always rested with the people, which acted through a complicated set of assemblies attended by all citizens in person (of course, not all inhabitants of Rome were citizens). This was similar to what went on in many Greek city-states. The general conduct of business was the concern of the Senate; it made laws and regulated the work of elected magistrates. It was in the form of tensions between the poles of Senate and people that the most important political issues of Roman history were usually expressed.

Somewhat surprisingly, the internal struggles of the early republic seem to have been comparatively bloodless. Their sequence is complicated and sometimes mysterious, but their general result was that they gave the citizen body as a whole a greater say in the affairs of the republic. The Senate, which concentrated political leadership, had come by 300

BC

or so to represent a ruling class which was an amalgamation of the old patricians of pre-republican days with the wealthier members of the

plebs

, as the rest

of the citizens were termed. The Senate’s members constituted an oligarchy, self-renewing though some were usually excluded from each census (which took place once every five years). Its core was a group of noble families whose origins might be plebeian, but among whose ancestors were men who had held the office of consul, the highest of the magistracies.

Two consuls had replaced the last kings at the end of the sixth century

BC

. Appointed for a year, they ruled through the Senate and were its most important officers. They were bound to be men of experience and weight, for they had to have passed through at least two subordinate levels of elected office, as

quaestors

and

praetors

, before they were eligible. The quaestors (of whom there were twenty elected each year) also automatically became members of the Senate. These arrangements gave the Roman ruling élite great cohesiveness and competence; for progress to the highest office was a matter of selection from a field of candidates who had been well tested and trained in office. That this constitution worked well for a long time is indisputable. Rome was never short of able men. What it masked was the natural tendency of oligarchy to decay into faction, for whatever victories were won by the plebs, the working of the system ensured that it was the rich who ruled and the rich who disputed the right to office among themselves. Even in the electoral college, which was supposed to represent the whole people, the

comitia centuriata

, organization gave an undue proportion of influence to the wealthy.