The New Penguin History of the World (52 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

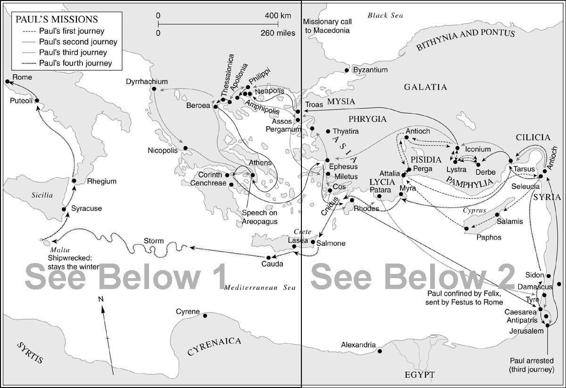

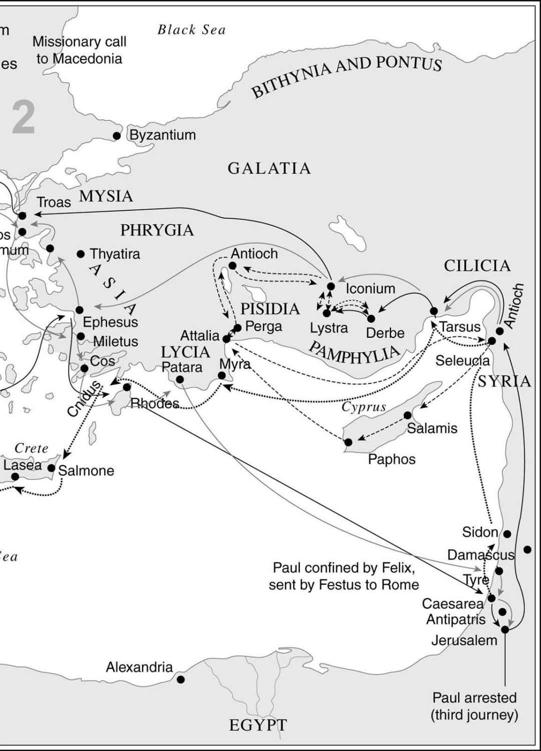

Somehow, Paul underwent a change of heart. From being a persecutor of the followers of Christ, he became one himself: it seems to have followed a sojourn of meditation and reflection in the deserts of east Palestine. Then, in

AD

47 (or perhaps earlier; dating Paul’s life and travels is a very uncertain business), he began a series of missionary journeys which took him all over the eastern Mediterranean. In

AD

49 an apostolic council at Jerusalem took the momentous decision to send him as a missionary to gentiles, who would not be required to undergo the circumcision, which was the most important act of submission to the Jewish faith; it is not clear whether he, the council, or both in agreement were responsible. There were already little communities of Jews following the new teaching in Asia Minor, where it had been carried by pilgrims. Now these were given a great consolidation by Paul’s efforts. His especial targets were Jewish proselytes, gentiles to whom he could preach in Greek and who were now offered full membership of Israel through the new covenant. The doctrine that Paul taught was new. He rejected the Law (as Jesus had never done), and strove to reconcile the essentially Jewish ideas at the heart of Jesus’s teaching with the conceptual world of the Greek language. He continued to emphasize the imminence of the coming end of things, but offered all nations, through Christ, the chance of understanding the mysteries of creation and, above all, of the relationship of things seen and things invisible, of the spirit and the flesh, and of the overcoming of the second by the first. In the process, Jesus became more than a human deliverer who had overcome death, and was God Himself – and this was to shatter the mould of Jewish thought within which the faith had been born. There was no lasting place for such an idea within Jewry, and Christianity was now forced out of the Temple. The intellectual world of Greece was the first of many new resting-places it was to find as the centuries went by. A colossal theoretical structure was to be built on this change.

The Acts of the Apostles give plentiful evidence of the uproar which such teaching could cause and also of the intellectual tolerance of the Roman administration when public order was not involved. But it often was. In

AD

59, Paul had to be rescued from the Jews at Jerusalem by the Romans. When put on trial in the following year, he appealed to the emperor and to Rome he went, apparently with success. From that time he is lost to history; he may have perished in a persecution by Nero in

AD

67.

The first age of Christian missions permeated the civilized world by sinking roots everywhere in the first place in the Jewish communities. The ‘Churches’ which emerged were administratively wholly independent of one another, though the community at Jerusalem was recognized to have an understandable primacy. There were to be found those who had seen the risen Christ and their successors. The only links of the Churches other than their faith were the institutional one of baptism, the sign of acceptance in the new Israel, and the ritual practice of the eucharist, the re-enactment of the rites performed by Jesus at his last supper with his disciples, the evening before his arrest. It has remained the central sacrament of the Christian Churches to this day.

The local leaders of the Churches exercised independent authority in practice, therefore, but this did not cover much. There was nothing except the conduct of the affairs of the local Christian community to be decided upon, after all. Meanwhile, Christians expected the Second Coming. Such influence as Jerusalem had flagged after

AD

70, when a Roman sack of the city dispersed many of the Christians there; after this time Christianity had less vigour within Judaea. By the beginning of the second century the communities outside Palestine were clearly more numerous and more important and had already evolved a hierarchy of officers to regulate their affairs. These identified the three later orders of the Church: bishops, presbyters and deacons. Their sacerdotal functions were at this stage minimal, and it was their administrative and governmental role which mattered.

The response of the Roman authorities to the rise of a new sect was largely predictable; its governing principle was that when no specific cause for interference existed, new cults were tolerated unless they awoke disrespect or disobedience to the empire. There was a danger at first that the Christians might be confounded with other Jews in a vigorous Roman reaction to Jewish nationalist movements, which culminated in a number of bloody encounters, but their own political quietism and the announced hostility of other Jews saved them. Galilee itself had been in rebellion in

AD

6 (perhaps a memory of it influenced Pilate’s handling of the case of a Galilean among whose disciples was a Zealot) but a real distinction from

Jewish nationalism came with the great Jewish rising of

AD

66. This was the most important in the whole history of Jewry under the empire, when the extremists gained the upper hand in Judaea and took over Jerusalem. The Jewish historian Josephus has recorded the atrocious struggle which followed, the final storming of the Temple, the headquarters of resistance, and its burning after the Roman victory. Before this, the unhappy inhabitants had been reduced to cannibalism in their struggle to survive. Archaeology has recently revealed at Masada, a little way from the city, what may well have been the site of the last stand of the Jews before it, too, fell to the Romans in

AD

73.

This was not the end of Jewish turbulence, but it was a turning-point. The extremists never again enjoyed such support and must have been discredited. The Law was now more than ever the focus of Jewishness, for the Jewish scholars and teachers (after this time, they are more and more designated as ‘rabbis’) had continued to unfold its meaning in centres other than Jerusalem while the revolt was in progress. Their good conduct may have saved these Jews of the dispersion. Later disturbances were never so important as had been the great revolt, though in

AD

117 Jewish riots in Cyrenaica developed into full-scale fighting, and in

AD

132 the last ‘Messiah’, Simon Bar Kochba, launched another revolt in Judaea. But the Jews emerged with their special status at law still intact. Jerusalem had been taken from them (Hadrian made it an Italian colony, which Jews might enter only once a year), but their religion was granted the privilege of having a special officer, a patriarch, with sovereignty over it, and they were allowed exemption from the obligations of Roman law which might conflict with their religious duties. This was the end of a volume of Jewish history. For the next 1800 years Jewish history was to be the story of communities of the

diaspora

(dispersion), until a national state was again established in Palestine among the debris of another empire.

The nationalists of Judaea apart, Jews elsewhere in the empire were for a long time thereafter safe enough during the troubled years. Christians did less well, though their religion was not much distinguished from Judaism by the authorities; it was, after all, only a variant of Jewish monotheism with, presumably, the same claims to make. It was the Jews, not the Romans, who first persecuted it, as the Crucifixion itself, the martyrdom of Stephen and the adventures of Paul have shown. It was a Jewish king, Herod Agrippa, who, according to the author of the Acts of the Apostles, first persecuted the community at Jerusalem. It has even appeared plausible to some scholars that Nero, seeking a scapegoat for a great fire at Rome in

AD

64, should have had the Christians pointed out to him by hostile Jews. Whatever the source of this persecution, in which, according to popular

Christian tradition, St Peter and St Paul both perished, and which was accompanied by horrific and bloody scenes in the arena, it seems to have been for a long time the end of any official attention by Rome to the Christians. They did not take up arms against the Romans in the Jewish revolts, and this must have soothed official susceptibilities with regard to them.

When they emerge in the administrative records as worth notice by government it is in the early second century

AD

. This is because of the overt disrespect which Christians were by then showing in refusing to sacrifice to the emperor and the Roman deities. This was their distinction. Jews had a right to refuse; they had possessed a historic cult which the Romans respected – as they always respected such cults – when they took Judah under their rule. The Christians were now clearly seen as distinct from other Jews and were a recent creation. Yet the Roman attitude was that although Christianity was not legal it should not be the subject of general persecution. If, on the other hand, breaches of the law were alleged – and the refusal to sacrifice might be one – then the authorities should punish when the allegations were specific and shown in court to be well founded. This led to many martyrdoms, as Christians refused the well-intentioned attempts of Roman civil servants to persuade them to sacrifice or abjure their god, but there was no systematic attempt to eradicate the sect.

Indeed, the authorities’ hostility was much less dangerous than that of the Christians’ fellow subjects. As the second century passed, there is more evidence of pogroms and popular attacks on Christians, who were not protected by the authorities since they followed an illegal religion. They may sometimes have been acceptable scapegoats for the administration or lightning-conductors diverting dangerous currents. It was easy for the popular mind of a superstitious age to attribute to Christians the offences to the gods which led to famine, flood, plague and other natural disasters. Other equally convincing explanations of these things were lacking in a world with no other technique for explaining natural disaster. Christians were alleged to practise black magic, incest, even cannibalism (an idea no doubt explicable in terms of misleading accounts of the eucharist). They met secretly at night. More specifically and acutely, though we cannot be sure of the scale of this, the Christians threatened by their control of their members the whole customary structure which regulated and defined the proper relations of parents and children, husbands and wives, masters and slaves. They proclaimed that in Christ there was neither bond nor free and that He had come to bring not peace but a sundering sword to families and friends. It was prescient of pagans to sense danger; in such views.

Christianity’s greatest contribution to a later western civilization would be its stubbornly prophetic and individualistic assertion that life should be regulated with reference to a moral guidance independent not only of government but of any other merely human authority. It is not hard, therefore, to understand the violent outbursts in the big provincial towns, such as that at Smyrna in

AD

165, or Lyons in

AD

177. They were the popular aspect of an intensification of opposition to Christianity which had an intellectual counterpart in the first attacks on the new cult by pagan writers.

Persecution was not the only danger facing the early Church. Possibly it was the least grave. A much more serious one was that it might develop into just another cult of the kind of which many examples could be seen in the Roman empire and, in the end, be engulfed like them in the magical morass of ancient religion. All over the Near East could be found examples of the ‘mystery religions’, whose core was the initiation of the believer into the occult knowledge of a devotion centred on a particular god (the Egyptian Isis was a popular one, the Persian Mithras another). Almost always the believer was offered the chance to identify himself with the divine being in a ceremony which involved a simulated death and resurrection, and thus to overcome mortality. Such cults offered, through their impressive rituals, the peace and liberation from the temporal which many craved. They were very popular.