The New Penguin History of the World (45 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

‘Plebs’, in any case, is a misleadingly simple term. The word stood for different social realities at different times. Conquest and enfranchisement slowly extended the boundaries of citizenship. Even in early times they ran well beyond the city and its environs as other cities were incorporated in the republic. At that time, the typical citizen was a countryman. The basis of Roman society was always agricultural and rural. It is significant that the Latin word for money,

pecunia

, is derived from the word for a flock of sheep or herd of cattle and that the Roman measure of land was the

iugerum

, the extent that could be ploughed in a day by two oxen. Land and the society it supported were related in changing ways during the republic, but always its base was the rural population. The later preponderance in men’s minds of the image of imperial Rome, the great parasitic city, obscures this.

The free citizens who made up the bulk of the population of the early republic were therefore peasants, some much poorer than others. They were legally grouped in complicated arrangements whose roots were sunk in the Etruscan past. Such distinctions were economically insignificant, though they had constitutional importance for electoral purposes, and tell us less about the social realities of republican Rome than distinctions made

by the Roman census between those able to equip themselves with the arms and armour needed to serve as soldiers, those whose only contribution to the state was to breed children (the

proletarii

) and those who were simply counted as heads, because they neither owned property nor had families. Below them all, of course, were the slaves.

There was a persistent tendency, accelerating rapidly in the third and second centuries

BC

, for many of the plebs who in earlier days had preserved some independence through possession of their own land to sink into poverty. Meanwhile, the new aristocracy increased its relative share of land as conquest brought it new wealth. This was a long-drawn-out process, and while it went on, new sub-divisions of social interest and political weight appeared. Furthermore, to add another complicating factor, there grew up the practice of granting citizenship to Rome’s allies. The republic in fact saw a gradual enlargement of the citizen class but a real diminution of its power to affect events.

This was not only because wealth came to count for so much in Roman politics. It was also because everything had to be done at Rome, though there were no representative arrangements which could effectively reflect the wishes of even those Roman citizens who lived in the swollen city, let alone those scattered all over Italy. What tended to happen instead was that threats to refuse military service or to withdraw altogether from Rome and found a city elsewhere enabled the plebs to restrict somewhat the powers of Senate and magistrates. After 366

BC

, too, one of the two consuls had to be a plebeian and in 287

BC

the decisions of the plebeian assembly were given overriding force of law. But the main restriction on the traditional rulers lay in the ten elected Tribunes of the People, officers chosen by popular vote, who could initiate legislation or veto it (one veto was enough) and were available night and day to citizens who felt themselves unjustly treated by a magistrate. The tribunes had most weight when there was great social feeling or personal division in the Senate, for then they were courted by the politicians. In the earlier republic and often thereafter, the tribunes, who were members of the ruling class and might be nobles, worked for the most part easily enough with the consuls and the rest of the Senate. The administrative talent and experience of this body and the enhancement of its prestige because of its leadership in war and emergency could hardly be undermined until there were social changes grave enough to threaten the downfall of the republic itself.

The constitutional arrangements of the early republic were thus very complicated, but effective. They prevented violent revolution and permitted gradual change. Yet they would be no more important to us than those of Thebes or Syracuse, had they not made possible and presided over the

first phase of victorious expansion of Roman power. The story of the republic’s institutions is important for even later periods, too, because of what the republic itself became. Almost the whole of the fifth century was taken up in mastering Rome’s neighbours and her territory was doubled in the process. Next, the other cities of the Latin League were subordinated; when some of them revolted in the middle of the fourth century they were forced back into it on harsher terms. It was a little like a land version of the Athenian empire a hundred years before; Roman policy was to leave her ‘allies’ to govern themselves, but they had to subscribe to Roman foreign policy and supply contingents to the Roman army. In addition, Roman policy favoured established dominant groups in the other Italian communities, and Roman aristocratic families multiplied their personal ties with them. The citizens of those communities were also admitted to rights of citizenship if they migrated to Rome. Etruscan hegemony in central Italy, the richest and most developed part of the peninsula, was thus replaced by Roman.

Roman military power grew as did the number of subjected states. The republic’s own army was based on conscription. Every male citizen who owned property was obliged to serve if called and the obligation was heavy, sixteen years for an infantryman and ten for cavalry. The army was organized in legions of 5000, which fought at first in solid phalanxes with long pike-like spears. It not only subdued Rome’s neighbours, but also beat off a series of fourth-century incursions by Gauls from the north, though on one occasion they sacked Rome itself (390

BC

). The last struggles of this formative period came at the end of the fourth century when the Romans conquered the Samnite peoples of the Abruzzi. Effectively, the republic could now tap allied manpower from the whole of central Italy.

Rome was now at last face to face with the western Greek cities. Syracuse was by far the most important of them. Early in the third century the Greeks asked the assistance of a great military leader of mainland Greece, Pyrrhus, King of Epirus, who campaigned against both the Romans and the Carthaginians (280–275

BC

), but achieved only the costly and crippling victories to whose type he gave his name. He could not destroy the Roman threat to the western Greeks. Within a few years they were caught up willy-nilly in a struggle between Rome and Carthage in which the whole western Mediterranean was at stake – the Punic Wars.

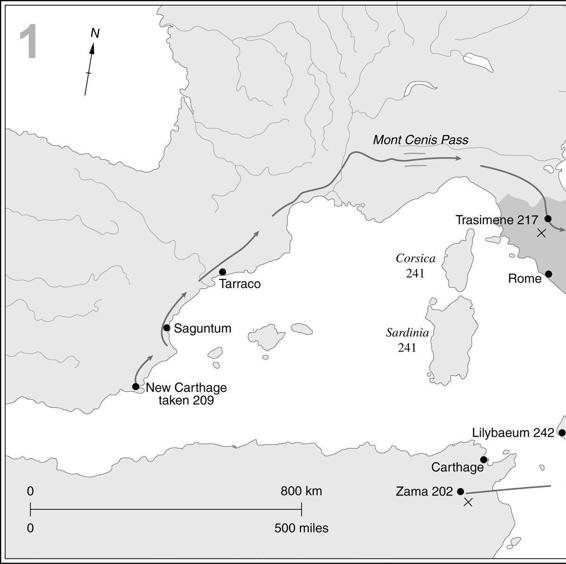

They form a duel of more than a century. Their name comes from the Roman rendering of the word Phoenician and, unfortunately, we have only the Roman version of what happened. There were three bursts of fighting, but the first two settled the question of preponderance. In the first (264–241

BC

) the Romans began naval warfare on a large scale for the first

time. With their new fleet they took Sicily and established themselves in Sardinia and Corsica. Syracuse abandoned an earlier alliance with Carthage, and western Sicily and Sardinia became the first Roman provinces, a momentous step, in 227

BC

.

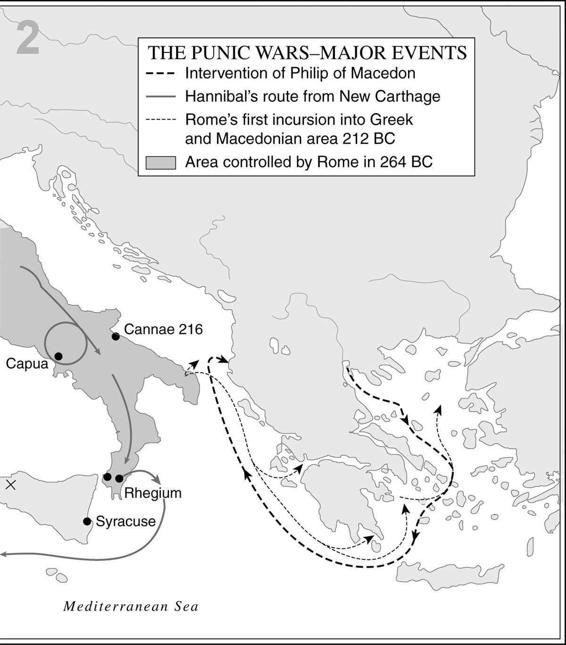

This was only round one. As the end of the third century approached, the final outcome was not yet discernible and there is still argument about which side, in this touchy situation, was responsible for the outbreak of the second Punic War (218–201

BC

), the greatest of the three. It was fought in a greatly extended theatre, for when it began the Carthaginians were established in Spain. Some of the Greek cities there had been promised Roman protection. When one of them was attacked and sacked by a Carthaginian general, Hannibal, the war began. It is famous for Hannibal’s great march to Italy and passage of the Alps with an army including elephants, and for its culmination in the crushing Carthaginian victories of Lake Trasimene and Cannae (217 and 216

BC

), where a Roman army twice the size of Hannibal’s was destroyed. At this point Rome’s grasp on Italy was badly shaken; some of her allies and subordinates began to look at Carthaginian power with a new respect. Virtually all the south changed sides, though central Italy remained loyal. With no resources save her own exertions and the great advantage that Hannibal lacked the numbers needed to besiege Rome, Rome hung on and saved herself. Hannibal campaigned in an increasingly denuded countryside far from his base. The Romans mercilessly destroyed Capua, a rebellious ally, without Hannibal coming to help her and then boldly embarked upon a strategy of striking at Carthage in her own possessions, especially in Spain. In 209

BC

‘New Carthage’ (Cartagena) was taken by the Romans. When an attempt by Hannibal’s younger brother to reinforce him was beaten off in 207

BC

the Romans transferred their offensives to Africa itself. There, at last, Hannibal had to follow them to meet his defeat at Zama in 202

BC

, the end of the war.

This battle settled more than a war; it decided the fate of the whole western Mediterranean. Once the Po valley was absorbed early in the second century, Italy was, whatever the forms, henceforth subject to Rome. The peace imposed on Carthage was humiliating and crippling. Roman vengeance pursued Hannibal himself and drove him to exile at the Seleucid court. Because Syracuse had once more allied with Carthage during the war, her presumption was punished by the loss of her independence; she was the last Greek state in the island. All Sicily was now Roman, as was southern Spain, where another province was set up.

Nor was this all. These events opened the way to the east. At the end of the second Punic War it is tempting to imagine Rome at a parting of the ways. On the one hand lay the alternative of moderation and the maintenance of security in the west, on the other of expansion and imperialism in the east. Yet this over-simplifies reality. Eastern and western issues were already too entangled to sustain so simple an antithesis. As early as 228

BC

the Romans had been admitted to the Greek Isthmian games; it was a recognition, even if only formal, that for some Greeks they were already a civilized power and part of the Hellenistic world. Through Macedon, that world had already been involved directly in the wars of Italy, for Macedon had allied with Carthage; Rome had therefore taken the side of Greek cities opposed to Macedon and thus began to dabble in Greek politics. When a direct appeal for help against Macedon and the Seleucids came from Athens, Rhodes and a king of Pergamon in 200

BC

, the Romans were already psychologically ready to commit themselves to eastern enterprise. It is unlikely, though, that any of them saw that this could be the beginning of a series of adventures from which would emerge a Hellenistic world dominated by the republic.

Another change in Roman attitudes was not yet complete, but was beginning to be effective. When the struggle with Carthage began, most upper-class Romans probably saw it as essentially defensive. Some went on fearing even the crippled enemy left after Zama. The call of Cato in the middle of the next century – ‘Carthage must be destroyed’ – was to be famous as an expression of an implacable hostility arising from fear. None the less, the provinces won by war had begun to awake men’s minds to other possibilities and soon supplied other motives for its continuation. Slaves and gold from Sardinia, Spain and Sicily were soon opening the eyes of Romans to what the rewards of empire might be. These countries were not treated like mainland Italy, as allies, but as resource pools to be

administered and tapped. A tradition grew up under the republic, too, of generals distributing some of the spoils of victory to their troops.