The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (54 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

All of these abdications made one thing very clear: the heavenly sovereign was no emperor, not in the sense of a Chinese or Byzantine or Persian emperor. He did not rule, as they did, controlling armies and laws. He shone, and in his light, power was dispersed to others. Fujiwara officials controlled the day-to-day running of the court and its rituals. The provinces farther away from the city were controlled by their governors, who were responsible for collecting their own taxes—and who quite often used those taxes for their own purposes, rather than passing them on to the capital.

17

They were not above padding the tax bills either, and both inside and outside of the capital, the farmers and small tradesmen of Japan found themselves under continual pressure to hand over more of their meagre profits. This extortion, unchecked by the heavenly sovereign, fell on a countryside already strained by Kammu’s two successive moves. Each change of the capital city had required a raise in taxes to pay for the new construction and the drafting of able-bodied farmers into a temporary workforce to build the emperor’s new residences. A note in the royal chronicles for 842, during the reign of the heavenly sovereign Ninmyo, gives us a glimpse of grotesque poverty just outside Heian’s own walls: “The Office of the Capital was ordered to gather up and burn some five thousand, five hundred skulls lying around,” the chronicler tells us. The peasants who lived along the Kamo river, which flowed past Heian, were so poor that they could not afford tombs or deep graves for their dead; instead they scratched holes in the sand for the bodies, and as the river wore the sand away, the bones were flung up onto the shore.

18

The heavenly sovereign Ninmyo abdicated in 850; he had married a Fujiwara noblewoman, and his half-Fujiwara son Montoku became the heavenly sovereign. Montoku, twenty-three when he inherited his crown, had little to do during his royal days. The Fujiwara officials were ruling the country on his behalf, and he seems to have spent most of his time in the women’s quarters of the palace. By the time he was in his early thirties, he had fathered twenty-seven children.

19

But his primary consort was Akira Keiko, daughter of the ambitious Fujiwara nobleman Fujiwara no Yoshifusa. Yoshifusa engineered the marriage, watched with satisfaction as Akira Keiko gave birth to a son and heir, and then leveraged his connection with the throne to be appointed Chief Minister,

daijo daijin

, in 857. The heavenly sovereign Montoku died just one year later, at the age of thirty-two. His son Seiwa, eight years old, was crowned his heir; and Yoshifusa, the child’s Fujiwara grandfather, had himself appointed as

Sessho

, or regent, for the underage king.

It was the first time that an “outsider,” someone not from the royal line, had been given the job of regent. But by this time, the royal line and the Fujiwara clan had become so intertwined that the whole concept of a separate royal line was merely symbolic—as symbolic as the power of the young heavenly sovereign. Seiwa sat on the throne as the polestar, beautiful, honored, and powerless; the Sessho ruled on his behalf.

Even when Seiwa reached the age of the maturity, the Sessho remained on. He was an official outside of the law, beyond the royal sphere, with his power derived from the heavenly sovereign but eclipsing its source. Yoshifusa even arranged Seiwa’s marriage for him, wedding him to Yoshifusa’s own niece (the young ruler’s first cousin once removed). This made him, simultaneously, the emperor’s grandfather, regent, and uncle-in-law; the marriage created one more tie between the royal line and the Fujiwara clan, one more point of reflected power. The young woman herself, Takaiko, was given no choice in the matter. She had a lover of her own, but later poems tell of his unpleasant fate: he was exiled from court, forced to enter a monastery, and did not see his beloved again until he had grown old and feeble.

20

In 872, Yoshifusa died, but he passed the power of his office on to his adopted son, Fujiwara no Mototsune. Heavenly Sovereign Seiwa was at this time twenty-two and in no real need of a regent. But Mototsune was anxious to exercise the full power of his office. Four years later, he convinced Seiwa to abdicate, at the age of twenty-six, and hand the crown over to the heir apparent, Seiwa’s five-year-old son Yozie.

To die and leave the throne to a child was often unavoidable. But to

abdicate

in favor of a child shows one thing clearly: the heavenly sovereign no longer needed to rule. The Sessho, refracting his glory, would rule for him. The sovereign himself needed merely to exist: a necessary, but passive, node of connection with the divine order.

Between 806 and 918, military governors, rebels, and Turks destroy the Tang and the period of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms begins, while rebel commanders and exiled princes divide Unified Silla into the Later Three Kingdoms

T

HE

T

ANG EMPIRE

was shrunken and struggling, but all was not lost. In the aftermath of the An Lushan rebellion, the Tang emperors had managed to restore a reasonably effective system of tax collection. The sale of salt was now a royal monopoly, pouring yet more cash into the royal coffers. The crown was weakened, but not poverty-stricken.

Taxes and salt may have been under royal control, but the outlying provinces that had once been firmly under Tang rule definitely were not. Far too many of the

fanzhen

, the military governors appointed by earlier emperors, had turned into mini-monarchs controlling their own lands. Some of these military commanders were of Chinese ancestry; many others were of “barbarian” descent, warrior chiefs who had been allowed to settle their people within Tang borders and had, in exchange, agreed to defend the Tang land against outside invaders.

The loyalty of the

fanzhen

to the Tang varied widely. Some of the border peoples, like the Turkish tribe of the Shatuo, were transforming themselves into Chinese, while others ignored the emperor at Chang’an. The borders of the Tang empire had gotten not just permeable, but indistinct. The farther from Chang’an a traveller got, the harder it was to figure out whether or not he had left Tang land.

1

In 806, the emperor Tang Xianzong began an attempt to restore his power in these outlying lands. In a series of wars fought between 806 and 817, he slowly whipped the

fanzhen

back into the fold. When he captured the recalcitrant governors, he brought them to the capital city and had them executed. By 820, he had almost managed to restore the palace’s control over the old Tang land.

2

And then, just as he reached for the final prize of a unified empire, the vigorous young emperor died. He was only forty-two, and it was whispered that two court eunuchs who resented the emperor’s power had poisoned him; it was more than whispered that his son and heir Muzong had a hand in the unexpected death. Whether or not this was true, Muzong ascended the throne and let his father’s conquests slip away. Both Tang Muzong and his successor, his son Tang Jingzong, were known for their devotion to banqueting and ball games; they allowed the court eunuchs to run the day-to-day operations of the palace, and one chronicler laments that “the business of the state was almost entirely given up.”

3

By 827, the

fanzhen

were once again entrenched in their independent fortresses, and the palace eunuchs were thoroughly in control of the doings at court. They murdered Tang Jingzong, who was eighteen and had ruled less than three years, and instead supported the coronation of Jingzong’s younger brother Tang Wenzong.

Tang Wenzong remained alive and on the throne for fourteen years, but only because he was willing to relinquish the real power of the throne to the

fanzhen

on the edges of his empire and the officials in his palace, most of whom were eunuchs (thus less likely to seize the throne in hopes of establishing a dynasty). This state of affairs could have led to chaos and disorganization, as in fact it had in Unified Silla. But the eunuchs did a perfectly adequate job of running the country. In 838, twelve years into Wenzong’s puppet reign, the Japanese monk Ennin travelled to Tang China. His travel diary chronicled a well-organized, efficient state that appeared to be prospering: he remarks, impressed, that there were over four thousand shops in one central district in the capital city Chang’an, that the canals were “lined on both sides with rich and noble houses quite without a break,” that the river was filled with merchant ships and boats carrying the royal salt.

4

Efficient administrators though they were, the eunuchs would have been helpless in any military crisis; they were bureaucrats, given no training in the art of warfare. But by pure good luck, no invasion threatened. No ambitious

fanzhen

tried to take over the center of the Tang empire. The kingdoms of Balhae and Unified Silla and Yamato Japan were preoccupied with their own affairs. During the rule of Tang Wenzong’s successor, the Uighur empire to the north was divided by civil war and disintegrated; nomads from the north took advantage of its weakness to invade and sack the Uighur capital, Ordu-Baliq, and its people fled to the south and west. And the Tibetan empire, which had for so long troubled the southwestern border of the Tang, was ripped apart by a religious war.

5

The tentative stability of the Tang meant that the emperors and their eunuchs could concentrate on trade, on that useful salt monopoly, on careful tax collection, and on literary pursuits. In 869, during the reign of the emperor Tang Yizong, the king of Unified Silla even sent his son, the Sillan crown prince, to study in the Chinese capital.

All continued well—until the dreaded military crisis erupted. It came not from outside, but from inside. And although it was not led by one of the

fanzhen

, it was precipitated by the same tension that many of them felt: that of an outsider who wished to become an insider.

In 874, a young man named Huang Chao took the civil service examination and failed it. He was furious. Since childhood Huang Chao had been known for his intelligence and his literary abilities and he could not believe that the exam had judged him unworthy. The examination system had been criticized before; a few decades earlier, the public official and poet Han Yu had complained bitterly that the training that prepared students to do well on the exams merely taught “literary tricks” and pat answers, and had nothing to do with real learning. Now Huang Chao, smarting from his failure, proclaimed that the exam system was nothing more than a tool of exclusion, used by the government to block the unwanted from official positions.

6

Huang Chao turned outlaw. Stationing himself in the northeast of China, near the coast and just south of the Yellow river, he began to sell salt illegally, breaking the government monopoly—which he believed to be unjust. He was soon joined by other malcontents. Several bad growing seasons in the north of China meant that too many farmers were hungry and desperate. The band of smugglers grew larger and began to indulge in Robin Hood escapades, robbing rich merchants on the nearby roads, raiding wealthy towns, and then attacking and killing foreign traders along the coast.

7

Tang troops were finally dispatched from Chang’an to arrest the troublemakers, but Huang Chao and his confederates fought back. More and more farmers and peasants joined their cause. Before long, the robber band had swelled into a full-fledged rebellion with over half a million followers.

Four years of fighting followed. The rebels captured Luoyang and fought their way far south, crossing the Yangtze and capturing Tang land all the way down to the city of Guangzhou. From this base Huang Chao turned back north and began to make his way towards Chang’an itself. In 880, he arrived at the walls of the capital city and captured it in what he later called a “blood bath.”

8

The emperor Tang Xizong, Tang Yizong’s successor, fled with his court from the city and fortified himself instead at the western city of Chengdu. In control of the capital city and the palace, Huang Chao ascended the throne and announced himself king of a new dynasty.

9

Tang Xizong, determined to fight back, hired Turkish mercenaries from the northern border tribes of the Shatuo to reinforce his damaged army. Like the

fanzhen

, they were a more or less independent military power on the outer edge of Tang power; unlike the

fanzhen

, who hoped to escape Tang control altogether, the Shatuo were outsiders who desperately wished to be insiders.

The Shatuo commander Li Keyong, a Turk who had already adopted a Chinese name and Chinese customs, led forty thousand horsemen south and helped Tang Xizong lay siege to Chang’an. In 882, outside Chang’an’s walls, the Tang army and the Turkish mercenaries together met an enormous rebel army commanded by Huang Chao. The Battle of Liangtianpo was a defeat for Huang Chao. He was driven northwards, away from Chang’an and the land he had already conquered, back towards the home territory of the Shatuo. Li Keyong followed him, harassing him all the way.

In this he was aided by one of Huang Chao’s former allies, Zhu Wen, who had deserted Huang Chao and gone over to the side of the Tang. He was given charge of part of the royal army, and together the two men worked to put the rebellion down.

The rebels met the government forces again in 884 on the banks of the Yellow river. This time, Huang Chao and his men were decisively defeated. Huang Chao, fleeing from the carnage, was cornered and committed suicide so that Li Keyong would not get the credit for his capture.

The emperor Tang Xizong rewarded Li Keyong by making him the military governor of most of the north. He then returned to Chang’an, but his re-entry was far from triumphant. The empire was in tatters. The cities of Luoyang and Yangzhou had been put to the torch; the city of Chang’an was destroyed and demoralized. “Chang’an lies in mournful stillness: what does it now contain?” mourned the poet Wei Zhuang:

Ruined markets and desolate streets, in which ears of wheat are sprouting.

Fuel-gatherers have hacked down every flowering plant in the Apricot Gardens,

Builders of barricades have destroyed the willows along the Imperial Canal….

All the pomp and magnificence of the olden days are buried and passed away;

Only a dreary waste meets the eye….

All along the Street of Heaven one treads on the bones of State officials.

10

Tang Xizong had kept his title, but his power was gone and the days of his dynasty were drawing to an end.

He was succeeded in 888 by his son Tang Zhaozong, who presided over a dying world. For two more decades, the empire lingered on, while the turncoat Zhu Wen and the Turkish general Li Keyong continued to grow in power. Li Keyong had extended his military governorship of the north into a minor kingship—just as

fanzhen

, given the chance, had always done. He had installed his own Shatuo allies in official positions throughout his realm and no longer acknowledged the rule of the Tang emperor.

11

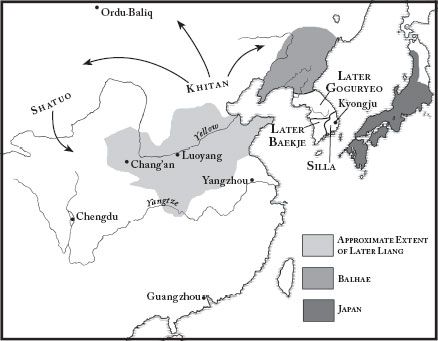

54.1: The Later Liang and the Later Three Kingdoms

He had also fallen out with his co-commander Zhu Wen. After the end of the rebellion, Zhu Wen had begun to resent the greater rewards given to Li Keyong. He had been slowly taking for himself more and more land between Chang’an and the borders of Li Keyong’s province. In 901 and 902, he tried to invade Li Keyong’s land, and both times was driven back.

But Zhu Wen had more luck in Chang’an itself. Fearing the power of the general Li Keyong, and hoping to keep Zhu Wen loyal, the emperor gave him a royal title. Zhu Wen accepted the title and then began a slow, careful campaign to isolate the emperor from his supporters: killing or exiling them as traitors, surrounding the unfortunate emperor with his own men, and finally ordering, in the emperor’s name, that the whole royal court be moved to the city of Luoyang.

12

This raised alarm all over the remnants of the empire, and from various cities, loyal officials and soldiers set out for Luoyang, determined to rescue the emperor. When Zhu Wen heard of their approach, he sent his own men to murder the emperor and then—loudly proclaiming his own loyalty to the crown—executed the assassins. The would-be rescuers, either deceived or giving up hope, withdrew.

Zhu Wen then authorized the coronation of the emperor’s thirteen-year-old son as Tang Aidi: a true puppet-king, thoroughly under the general’s control. The outsider had arrived almost at the center of the Tang empire. He was king in all but name.

The name came next. The following year, Zhu Wen forced Tang Aidi to decree the murder of his nine remaining brothers and all the ministers who were still loyal to the royal family. They were strangled, and their bodies were thrown into a nearby river. Now, Zhu Wen was ready to claim the title for himself. He forced the sixteen-year-old emperor to abdicate and founded his own dynasty, the Later Liang.

13

It was a short-lived dynasty: the Later Liang would only survive from 907 until 923. But the abdication of the last Tang emperor (and his murder the following year) plunged China into a roiling mass of struggle between minor kingdoms. This period, known as the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms, would last until 960. In a span of just over fifty years, the

fanzhen

would create and then lose a slew of minor realms. Five ruling dynasties would rise and fall in the north; more than ten separate kingdoms would appear and disappear in the south.

*