The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (53 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

As Krum drew near to the city walls, Michael Rangabe agreed to acknowledge Charlemagne’s claim to be emperor. But the language of the agreement reveals its grudging nature. Michael Rangabe hailed Charlemagne as emperor of the Franks and praised him for the establishment of his Roman empire; but nowhere, at any time, did he call him emperor of the Romans. In exchange for this unwilling admission, Charlemagne agreed to stop contesting Byzantine possession of the Italian city of Venice and its port.

15

Reassured that Krum would now find an enemy at his back, Michael Rangabe resumed the battle against the Bulgarians. By 813, he had recaptured some of the Thracian territory and had set his army up for a massive, war-ending confrontation near Adrianople.

The two armies met on June 22. “The Christians were grievously worsted in battle,” writes Theophanes, “and the enemy won, so much so that most of the Christians had not even waited for the first clash before they took to headlong flight.” Clearly, Michael’s army had serious doubts about the wisdom of the assault.

16

Michael Rangabe was forced to flee back to Constantinople; Krum chased him to its walls and then laid siege to the city. Once back inside the walls, Michael Rangabe offered to abdicate, in the face of almost certain assassination should he remain on the throne. The army and the officers had “despaired of being ruled by him any longer” and had decided that Leo the Armenian, military governor of the Byzantine lands in Asia Minor, should be acclaimed as the new emperor.

After a token protest, Leo the Armenian accepted and marched from Asia Minor to Constantinople. He fought his way into the city and was crowned Emperor Leo V by the patriarch on July 12, while Michael and his sons took refuge in a church and put on monks’ clothes to demonstrate their willingness to give up power. This saved their lives but not their manhood; Leo V’s first act was to castrate Michael’s sons before sending them off into monastic exile, wiping out any chance that they might later claim the legitimate rule of Byzantium.

17

In the meantime Krum was terrifying the city, not least by carrying out a demon-summoning sacrifice right in front of the Golden Gate. He was, in the words of Theophanes, “the new Sennacherib”: the Assyrian king of ancient times had tried to wipe out the people of God when he attacked Jerusalem,

*

and Krum was doing the same.

18

Leo V offered to meet with Krum under a flag of truce. But he had no intention of honoring the conventions of such a meeting. Conventions governed Christian monarchs, but they did not constrain emperors to treat barbarians like real kings. When Krum approached the meeting place, just outside the city walls, Leo’s men tried to assassinate him. “Through their incompetence,” Theophanes writes, “they merely wounded him and did not inflict a fatal blow.”

19

Krum escaped, but he was too weakened by his injuries to continue the siege. In fury, he ordered his army to sack the land around Constantinople before he was forced to retreat back towards his homeland to recover. On the way, he burned a good part of Thracia and took scores of captives, whom he settled in Bulgaria as exiles and constant reminders of the Byzantine treachery.

Once recovered, Krum began to plan a final assault on Constantinople. But he was still preparing for the attack when, in 814, he died. Without Krum’s fury behind it, the Bulgarian juggernaut lost some of its momentum. Leo V, sending his army against the Bulgarians in an attempt to drive them back out of Thracia, began to have some success. Before long, Krum’s successor, his son Omurtag, agreed to a thirty-year peace.

The crisis had ended, but the wild man had almost brought the empire of the Greeks down. More than that, Krum’s reign began a Bulgarian dynasty that would control the country without interruption for a century. With the help of the Christianity that was already spreading from the Byzantine captives through the Bulgarian population, the descendents of Krum would begin to shape the Bulgarian horde into a state that could take its place among the kingdoms of the west.

20

Between 790 and 872, the aristocratic clans take control of Silla, and the Fujiwara take control of Japan

T

HE KINGS OF

Unified Silla and Balhae, east of the crumbling Tang, were adjusting to the new landscape. In the absence of the Tang soldiers who had kept hostilities alive between them, they had worked out a treaty. For the first time in decades, the Sillans were not fighting an unending war; they could put some thought instead into Silla’s internal workings.

These were not in the best of shape. By the eighth century, power in Silla was based almost entirely on bloodline, known as “bone rank.” An aristocrat whose parents were both of royal descent could boast “Hallowed Bone” status; if only one parent was royal, the child was “True Bone.” Until the middle of the seventh century, only Hallowed Bone aristocrats had ruled in Silla, but after the time of King Muyeol the Great (who had begun the unification of the peninsula by conquering Baekje in 660) True Bone aristocrats had held the Sillan throne.

1

Below the privilege level of those who could claim royal parentage were layers and layers of nobles who held various “head ranks” in decreasing importance, according to the purity of their family descent. There were seventeen bone ranks in all, and those not born to rank could count on a life without privilege. “In Silla, the bone rank is the key to employment,” an official named Seol Kyedu had written, in disgust. “If one is not of the nobility, no matter what his talents, he cannot achieve a high rank. I wish to travel west to China.”

2

Seol Kyedu did eventually go to China, where he hoped to earn rank by performing his duties well; the Confucian academies of eighth-century China allowed diligent students to work their way up through the ranks by demonstrating virtue and mastery of the orderly rituals that gave Confucian society its framework. But back in Silla, the bone rank system continued to congeal Sillan society into elaborate and unmoving stratifications, concentrating power only in the hands of the aristocrats and barring capable commoners from ever rising higher.

Around 790, King Wonseong of Silla began to work out a way to bypass these stiff, unyielding categories. Wonseong was True Bone by birth, but he was not in the direct royal line; he had been crowned five years before as the successor to his cousin Seondeok, who had died without sons. Wonseong owed his power to the very True Bone noblemen whose insistence on hereditary privilege was weakening the country.

Nevertheless, he was determined to get capable administrators back into power; so three years after his coronation, he installed a new state examination system. Rather than claiming official positions because of bone rank, candidates would have to show understanding of the Chinese texts and principles taught in the National Confucian Academy, which had been founded in Goguryeo in the fourth century and had managed to survive during the following chaotic centuries. King Wonseong built his new examination system around its teachings: virtue and intelligence, not mere social connections, were the qualities Silla needed in its leaders.

3

This return to an emphasis on learning, rather than mere heritage, was supported by Confucian monks such as Seol Chong, who grew famous for his ability to take Chinese classics and transcribe them into the language spoken by the people: “He interpreted the Nine Classics in the vernacular, and taught the young,” his biographer tells us in the

Samguk sagi

.

4

This was no easy task. Since writing had come to the Korean peninsula from China, Chinese characters were used by the learned, but they were used primarily to write in Chinese, and the language of Silla still remained without a writing system of its own. To finish his translations, Seol Chong was forced to invent a new system that used Chinese characters to represent Sillan words. The match between characters and words was awkward and imperfect, with tens of thousands of Sillan words left unwritten, but Seol Chong’s method survived for almost seven hundred years. The peninsula, very slowly, was inching out from beneath the vast umbrella of Chinese culture.

5

Like Seol Chong’s writing system, Wonseong’s reforms were imperfect. His attempts to open the government up to those of lower (or no) bone ranks were unpopular with the True Bone aristocrats who saw their hold on power loosening. The most powerful official in the Sillan government, the vice minister of state (

chipsabu sirang

), led the resistance to Wonseong’s efforts, and the king’s position was further weakened when his son died before him, leaving a grandson in poor health as his only heir. When King Wonseong died in 798, the grandson, King Soseong, ruled for less than two years before his own death; Soseong’s young son Aejang was then crowned, but he was not yet thirteen and power was held by his uncle, who served as his regent.

6

This brought Unified Silla into a time of slow decline, known to historians as the Late Period. The turnover of rulers was frequent and violent. In 809, young King Aejang was murdered by his uncle, who ascended the throne as King Heondeok. Immediately Heondeok had to put down a rebellion, led by a descendent of King Muyol who used the excuse of the usurpation to declare himself king in the central city of Ch’ungju. The revolt was quashed, rose up again under the rebel leader’s son, and was quashed a second time.

7

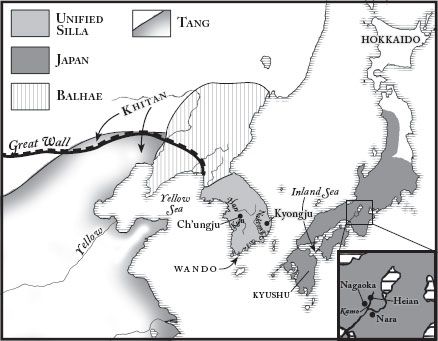

53.1: Unified Silla and Japan

Wonseong’s descendents remained on the throne, but the monarch was losing his mandate. And although the aristocracy of Silla had joined in resisting the king’s reforms, the nobles didn’t stay united for long. Instead, men of high bone rank collected private armies and began to fight amongst themselves for the chunks of power they had pried from the king’s hands. In struggling to keep the power to which they had been born, they inadvertently began to change the basis of that very power: increasingly, the size and skill of a man’s private army, not his bone rank, became the source of his influence.

8

The usurping king Heondeok died in 826. His successor, his brother Heungdeok, faced a struggling, armed countryside. The king’s forces had withdrawn inwards, towards the capital. Pirates from China roamed the coast, blocking the trade routes, kidnapping unwary Sillans and selling them into slavery. When Heungdeok’s young commander Chang Pogo asked for permission to establish a coastal garrison on the southwestern island of Wando, Heungdeok agreed at once: “The king gave Chang an army of ten thousand men,” the

Samguk sagi

tells us, “and bade him pitch camp on the island.” Chang’s patrol of the Yellow Sea drove most of the pirates out of Silla’s waters, but it also made him increasingly powerful; in his offshore base, out of sight of the king, he built himself a little private kingdom of his own.

9

When Heungdeok died without sons, open war broke out. His cousin and nephew fought over the throne; one was killed, the other committed suicide after less than a year on the throne, and a third relative claimed the crown. He too was removed in a matter of months by Chang Pogo, now master of the Yellow Sea, and Chang Pogo’s ally Kim Ujing. Together, the two men marched into the capital of Kyongju; Kim Ujing had himself crowned as King Sinmu, and Chang Pogo took up the position of power behind the throne.

Sinmu lasted for all of four months before an illness struck him down. His son Munseong was crowned in his place. But unlike his predecessors, Munseong managed to hang on to the throne for almost two decades—in large part because the Sillan nobility and their private armies were beginning to work out a satisfactory division of power. Rather than fighting for control of the capital city and the crown, they turned outwards; like Chang Pogo, they built themselves little private enclaves in outlying areas, where they reigned supreme. From their personal kingdoms, they traded—as Chang Pogo had—with the merchants of Tang China and with Japan, building their wealth as well as their power. King Munseong survived so long, in part, because he had become increasingly irrelevant.

10

In 846, Chang Pogo—who had provided the blueprint for these private kingdoms—proposed to marry his daughter to King Munseong, which would have given him a royal connection to add to his private army and his control of the sea. This was too much power for the True Bone aristocrats to take, and several of them joined together to mastermind Chang Pogo’s assassination.

11

This left Munseong on the throne but not in control. In less than a century, Unified Silla had become a country unified only in name. The most powerful aristocrats with the largest private armies erected fortresses at the center of their domains, ruling them almost as independent petty kings; they were called “castle lords” and exercised the right to collect taxes for themselves, without passing any of the money on to the putative center of government in Kyongju. The Buddhist monasteries that dotted the countryside took advantage of the king’s weakness to do the same, collecting land and tax revenues on their own account. Farmers and tradesmen, with no armies and no protection from the king, increasingly began to turn outlaw, and robber bands roamed through the hills.

12

Silla was tottering, and about to fall.

J

UST ACROSS THE WATER

to the east, a few clouds had begun to drift across the light cast by the heavenly sovereign of Japan, the polestar of his people.

Heavenly Sovereign Kammu sat on the throne, but he no longer ruled from Nara, the capital where the Yoro Code had been published. Instead, he had decided to break with the past. Now he ruled from a brand new court, thirty miles northwest, in the city of Nagaoka.

*

Kammu was the polestar of Japan, the country’s connection with the divine, the guarantor of order and law—but these resounding responsibilities were rapidly becoming symbolic. Power in Japan was scattered through the countryside, where clan leaders continued to claim their own authority. The chronicles from Kammu’s reign suggest that the monasteries and aristocrats of Nara had been actively gathering more and more wealth and power to themselves; in the year of the move to the new court, one account tells us, the “Buddhist temples in the capital were forbidden to accumulate wealth in an unreasonable manner,” while “the wealthy were forbidden to make loans to the poor in exchange for mortgages on their homesteads.” Like the monasteries, the aristocrats had been lending money at usurious rates, and claiming the farms of those who could not pay.

13

One particular aristocratic clan, the Fujiwara—descendents of Nakatomi no Kamatari, lifelong friend of the heavenly sovereign Tenji—had become more powerful in Nara than all the rest. The Fujiwara clan had inherited from Nakatomi no Kamatari the privilege of overseeing court rites and rituals, a responsibility that gave Fujiwara officials control over the center of the palace. By the beginning of Kammu’s rule, there were no fewer than four major branches of the family living in and around the capital city.

Kammu moved to Nagaoka, in large part, to get away from the Fujiwara courtiers who surrounded him at every moment of the day. The move was made in a frenzy, almost desperate in its haste; three hundred thousand men, working around the clock, built an entire royal complex in less than six months. But although he could leave Nara behind, he could not escape the tentacles of Fujiwara power. His chief consort was the daughter of a Fujiwara nobleman; the posts of “Great Minister of the Right” and “Great Minister of the East” were held by Fujiwaras; and he was forced by necessity to appoint a Fujiwara official as overseer of his new capital city.

14

For ten years, Heavenly Sovereign Kammu lived in his expensive palace in Nagaoka. He was battered by bad luck, illness, death in his family, and bloody infighting among his court officials, and by 794 he had decided that a curse hung over the city. He would not go back to Nara, which had been equally troublesome for him. Instead he moved the capital again, this time to the city of Yamashiro-no-kuni. Rather wistfully, he ordered it renamed Heian-kyo, “Capital of Peace.”

15

This time the move stuck. Nagaoka slowly crumbled away, while Heian—modern Kyoto—remained the capital of Japan for nearly a thousand years.

*

Kammu died in 806, after ruling for over two decades and fathering thirty-two children. Between 806 and 833, he was succeeded by three of his sons in turn. These sons shared a single characteristic: each one abdicated, handing the throne over to the next. The oldest, Heizei, was on the throne for only three years, when he became seriously ill and abdicated in favor of his younger brother Saga.

†

After fourteen years, Heavenly Sovereign Saga abdicated as well, and the throne went to the third brother, Junna. Junna reigned for ten years before handing the crown to his nephew Ninmyo, Saga’s twenty-three-year-old son, in 833.

16