The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (49 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

48.2: The Early Abbasid Caliphate

In 763, al-Mansur sent an Abbasid army to al-Andalus, in an attempt to bring it back to the Abbasid empire. When Abd ar-Rahman fought back and defeated it, al-Mansur decided that it would be wisest to abandon al-Andalus to the Umayyads in order to keep manpower strong in the east.

The Umayyad caliphs had slowly shifted their base of power closer and closer to the Mediterranean Sea, ending up in Syria, closer to the center of the Islamic empire. But the Abbasids had recentered themselves in the lands that had once been Persia, putting distance between themselves and the western part of the empire.

11

They also grew increasingly autocratic. Al-Mansur, like his brother, began his caliphate with murder; he arranged the assassinations of a number of prominent Shi’a leaders who had refused to support the Abbasid claim to power. He continued on as he had begun, ruthless and authoritarian, using his network of spies to root out dissent and ordering his enemies beaten, imprisoned, and executed. His intelligence was so frighteningly efficient that he was rumored to have a magic mirror that told him who was loyal and who was planning revolt.

12

The center of Baghdad, which contained his elaborate royal residence, was home to more and more ornate buildings—a whole complex that housed the caliph and all of his family in royal luxury. In the hands of al-Mansur, the spiritual authority of the caliph took a definite second place to political ambitions, and the Abbasid caliph began to look more and more like an emperor.

13

Between 737 and 778, the pope anoints the king of the Franks, the king of the Franks protects the pope, and the Iron Crown of the Lombards goes to Charles the Great

I

N

737,

THE DO-NOTHING KING

of the Franks, Theuderic IV, died, and Charles Martel did not bother to appoint another ruler. He was mayor of the palaces of the Franks,

dux et princeps Francorum

, the most prominent Christian warrior in all of the old Roman lands, and he had more power than anyone else in the western landscape—with the possible exception of the Lombard king Liutprand.

So when Pope Gregory III fell out with Liutprand in 738, he appealed to Charles Martel for help. The argument began with the duke of Spoleto, who defied an order given by the Lombard king and then fled to Rome for sanctuary. When the pope refused to hand him over to the king, Liutprand expressed his displeasure by taking back bits of the brand-new Papal State and occupying them himself. Cut off from Constantinople, Gregory had no one else to help him, and so he sent a desperate message to Martel. “In our great affliction, we have thought it necessary to write to you,” Gregory began. “We can now no longer endure the persecution of the Lombards…. You, oh son, will receive favor from the same prince of apostles here and in the future life in the presence of God, according as you render speedy aid to his church and to us, that all peoples may recognize the faith and love and singleness of purpose which you display in defending St. Peter and us and his chosen people. For by doing this you will attain lasting fame on earth and eternal life in heaven.”

1

The letter earns Gregory III partial credit for first articulating one of the goals that would motivate later crusaders: salvation, offered to those who fought in the name of the church. Unfortunately, it didn’t work with Charles Martel. The

dux et princeps Francorum

sent a present back to Gregory but declined to get involved. He and Liutprand had fought side by side at least once, and making enemies of the Lombards would gain him absolutely nothing (apparently he wasn’t convinced by Gregory’s redemptive rhetoric).

2

The standoff in Italy dragged on for several more years and was finally resolved by the death of everyone involved; Charles Martel and Pope Gregory III died in 741, and Liutprand died in 744 after an astounding thirty-two years as king of the Lombards. It had been a relatively minor political tangle, but Gregory’s appeal to Charles Martel had revealed a shift in the landscape. In a universe where the protection of the Byzantine emperor had been whisked away, the bishops of Rome were on their own, forced to make alliances with whatever power might be willing to protect them.

In 751, even the nominal claim of the emperor to rule in Italy was destroyed. The Lombards captured Ravenna, under the guidance of the aggressive new Lombard king Aistulf, and took the last exarch captive. A few patches of Italian land remained loyal to the emperor—the city of Venice, notably, declared itself still Byzantine—but now there was no Byzantine government on the peninsula. Constantinople had no representative, Venice and the other Byzantine cities were forced to govern themselves, and the pope was entirely on his own.

Unlike Charles Martel, though, the new

dux et princeps Francorum

was willing to protect Rome from hostile Lombards—in return for a favor.

After Charles Martel’s death, his two sons Carloman and Pippin the Younger had inherited his power, Carloman as mayor of the palace in Austrasia and Pippin the Younger in Neustria. The brothers had decided to put a figurehead king on the Frankish throne, which had been empty for seven years. Their choice was Childeric III; he was the son of the previous king, but his lineage was irrelevant since he took no part in governing.

Neither, after a few years, did Carloman. In 747, at the age of forty, he left his wife and children in the care of his younger brother and went to Rome to be consecrated as a monk. It was the culmination of a lifelong dream; despite his years in the mayor’s palace at Austrasia, he had, as Fredegar tells us, a “burning for the contemplative life.” According to Charlemagne’s biographer Einhard, Carloman tried to live in a monastery near Rome but was continually disturbed by Frankish noblemen coming to visit him. So shortly after his consecration, he travelled to Monte Cassino, to the monastery established by Benedict himself, where the rules of silence and isolation were strictly observed. “There,” Einhard writes, “he passed in the religious life what remained of his earthly existence.”

3

This left Pippin the Younger as sole mayor, and in 751 he decided to remove Childeric III and claim the throne himself. Yet that lingering regard for royal blood caused him to search for a greater sanction than himself for his usurpation of the throne.

And so he sent two men south to Rome with a brief message for the pope, Gregory III’s successor Zachary. The official chronicles of the Frankish kings,

Annales Regni Francorum

, give us a terse account:

[They] were sent to Pope Zachary to ask whether it was good that at that time there were kings in Francia who had no royal power. Pope Zachary informed Pippin that it was better for him who had the royal power to be called king, than the one who remained without royal power. By means of his apostolic authority, so that order might not be cast into confusion, he decreed that Pippin should be made king.

4

Zachary, facing the hostile Aistulf, was willing to trade the church’s approval for protection from the Lombards.

Pippin ordered Childeric III tonsured and sent to a monastery, where he died five years later, the last of the Merovingians. Pippin was crowned the first king of the Carolingian dynasty in the city of Soissons, in a brand-new sacred ceremony that involved anointing with holy oil in the manner of an Old Testament theocratic king.

*

Zachary died in 752, but his successor, Pope Stephen II, was careful to put himself in a position to reap the benefits of that coronation. In 754, he travelled north into the lands of the Franks and re-anointed Pippin in an even more elaborate ceremony, which also included the anointing of his sons, seven-year-old Charles and three-year-old Carloman, as his heirs. “At the same time,” according to an anonymous addition to Gregory of Tours’s history of the Franks, “he bound all the Frankish princes, on pain of interdict and excommunication,

†

never to presume in future to elect a king begotten by any men except those confirmed and consecrated by the most blessed pontiff.”

5

He had tied the Frankish king’s power to the authority of the pope, and King Pippin responded by marching across the Alps down into Italy, driving Aistulf out of the papal lands and the lands once governed by the exarch, and giving all of them to the pope. Aistulf’s army was badly defeated, and he was forced to recognize Pippin as his overlord. After Aistulf was thrown from his horse while hunting, and died in 756, Pippin chose the Lombard nobleman Desiderius to be the next king of Italy. In half a decade, he had become not only king of the Franks but the de facto ruler of Italy as well.

6

Pope Stephen II didn’t do badly either. He now ruled over a much expanded papal kingdom, which included both Rome and the old imperial center of Ravenna. To justify his possession of these lands, he presented Pippin with a document that (he claimed) had been written by Constantine and had been in the possession of the church ever since. In it, Constantine explained that the fourth-century pope Sylvester had healed him of a secret case of leprosy. In gratitude, he decreed that the papal seat “shall be more gloriously exalted than our empire and earthly throne,” that the pope would henceforth be supreme over “the four chief seats [of the church]—Antioch, Alexandria, Constantinople, and Jerusalem—as also over all the churches of God in the whole world,” and that Constantine himself was handing over to the pope “the city of Rome and all the provinces, districts and cities of Italy…. We are relinquishing them, by our inviolable gift, to the power and sway of himself and his successors.”

7

This document had been forged by some talented cleric, and the ink on it was barely dry. Pippin, who was not an idiot, undoubtedly knew this. But the popes had given him the authority he craved, and in return he was willing to award them power over Rome and the surrounding lands. The forgery, known as the “Donation of Constantine,” gave the transfer of authority a spurious sort of legitimacy.

But as long as no one examined it closely, spurious legitimacy served the purposes of everyone involved perfectly well.

F

IVE YEARS AFTER

al-Andalus became entirely independent from Baghdad, King Pippin of the Franks died.

He left his crown jointly to his sons Charles, now twenty-one, and Carloman, eighteen.

*

Both young men had been anointed along with him in 754 and so could claim to rule with the approval of God. They divided the administration of the empire, although not along the traditional Neustrian-Austrasian lines; instead, Charles ruled the northern lands and the coast, and Carloman took control of the southern territories.

Two years after his accession, Charles married the daughter of Desiderius, the king of the Lombards whose accession Pippin had supervised. “Nobody knows why,” writes Einhard, “but he dismissed this wife after one year.” In her place, he married an Alemanni girl named Hildegard, who was only thirteen years old. This gave him a useful connection with the eastern region of his empire where the sometimes-troublesome Alemanni people lived. Naturally, it infuriated the Lombard king, who proposed to Carloman that they unite together to destroy Charles; but in 771, just as the plan was being formed, Carloman died.

8

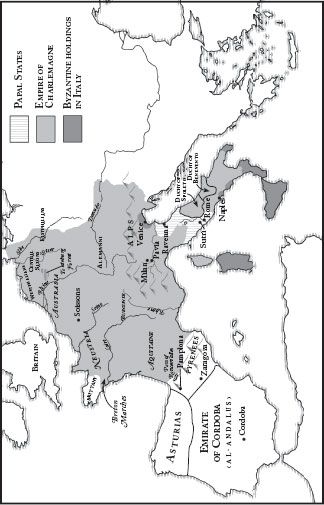

49.1: Charlemagne’s Kingdom

49.1: The Iron Crown of the Lombards, made of gold and precious stones with the iron band (said to be a nail from Christ’s cross) visible inside.

Credit: Scala/Art Resource, NY

Charles now ruled as sole monarch of all of the Frankish lands. Almost at once, he began to enlarge them through conquest. In 772, he set off to fight against the Saxons, just across the Rhine river. He was not yet thinking about the south, where the Lombard king Desiderius was still planning an attack. First, Charles wanted to expand his empire to the north; the land around the Rhine was rich, and the Saxon tribes were not well united. They fell into three main divisions—the central Saxons on the Weser river, the Eastphalians on the Elbe, and the Westphalians closer to the coast—but rarely fought together.

9

Charles pushed into the Saxon land in 772 and beat his way through the disorganized Saxon resistance into the Teutoburg Forest, where he ordered his men to destroy the most sacred shrine of the Saxons: the Irminsul, a great wooden pillar representing a tree trunk which symbolized the sacred tree that supported the vault of the heavens. He intended to show the Saxons that, as the God-appointed Christian king, he dominated both the Saxons

and

their gods. But the destruction of the Irminsul would haunt him. The Saxons were not politically united enough to mount a strong defense, but they held a single set of religious beliefs, and for decades to come the destruction of the Irminsul remained in their memories.

10

Leaving the Saxons temporarily subdued, Charles returned home and prepared to march into Italy. The following year, he crossed the Alps, set on punishing Desiderius for his plots and aiming to claim Italy for his own.

Desiderius and the Lombard army met him in the north of Italy, but Charles pushed the Lombard king back into his capital city of Pavia and laid siege to it. The siege lasted nearly a year; Charles (in the words of his biographer) “did not stop until he had worn Desiderius down and had received his surrender.”

11