The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (83 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

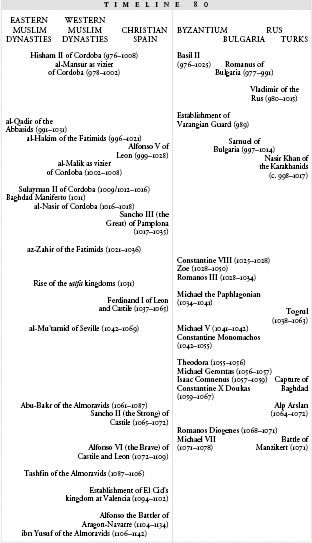

80.1: The Battle of Manzikert

Togrul’s triumphs in the south made the Byzantine army nervous; Michael the Aged did not inspire confidence in them. In 1057, the soldiers in Constantinople proclaimed their own commander, Isaac Comnenus, as emperor in the old man’s place. Michael the Aged offered to make him heir to the throne instead, but the people of Constantinople rioted, clamoring for Isaac. Michael VI had neither the energy nor the ambition to fight popular opinion. He abdicated peacefully and became a monk, dying two years later in his bed.

Constantinople celebrated the coronation of the new emperor. At last a soldier sat on the throne, a man who could drive back the Turkish advance. “All the populace of the city poured out to honour him,” Psellus writes. “Some brought lighted torches, as though he were God Himself, while others sprinkled sweet perfumes over him…. There was dancing and rejoicing everywhere.”

14

Unfortunately their hopes were dashed. Isaac Comnenus had a short and unimpressive tenure as emperor. He almost immediately made himself unpopular at court by proposing massive government reforms, and then—before he could carry most of them out—he grew ill, probably with pneumonia, and died. In his place, the bureaucrat Constantine Doukas was crowned, and although Constantine Doukas managed to stay in power for eight years, he paid little attention to the Turkish advances in the east. Not until 1068 did Constantinople get another soldier on the throne: the general Romanos Diogenes, who was crowned as Romanos IV, senior co-emperor along with Constantine Doukas’s sons.

Togrul, sultan of the Turks, had died of old age in 1063, leaving no sons. His nephew Alp Arslan (the name means “valiant lion”) had inherited his power and now led the Turks. He had his eye on the Byzantine land in Asia Minor and Romanos, recognizing the danger of Turkish growth, finally organized a campaign against the eastern border. Driving forward against the Turks, he pushed into the land they had already taken. In 1070, in a series of hard-fought battles, he managed to drive them back across the Euphrates. His years of campaigning had taught him the best way to deal with the lightly armed, fast-moving Turkish cavalry: keep the army bunched together, not spread out into a line, with bowmen protecting the slow, heavily armed cavalry on all sides.

15

Alp Arslan’s retreat had been a strategic one, allowing him to regather his forces. In 1071, he advanced again into Byzantine territory, and Romanos marched out to meet him at the head of sixty thousand soldiers.

But this time Romanos IV suffered from a severe attack of overconfidence. He didn’t know exactly where Alp Arslan and the bulk of his army had camped, and rather than holding his men together until he could get firm intelligence, he divided his army in half and sent thirty thousand men off to attack a nearby fortress. He marched with his remaining men to the city of Manzikert, right on the frontier between Byzantine and Turkish territory, and captured it.

All this time, Alp Arslan was just beyond Manzikert, keeping tabs on the emperor’s movements. Three days after the capture of Manzikert, as Romanos IV advanced cautiously into Turkish territory, he met what appeared to be a band of Turkish raiders. He drew up his army in a single line to drive them back. They retreated in front of him; delighted with his victory, he led the Byzantine troops after them, pursuing them on into the late afternoon.

But the raiders were merely the front edge of Alp Arslan’s massive force. As soon as the sun set, the Turks surrounded the strung-out army and massacred them in the twilight. “It was like an earthquake with howling, sweat, a swift rush of fear, clouds of dust,” one of the survivors later wrote. “Each man sought safety in flight.” Most of the Byzantine troops were caught and killed as they tried to escape; Romanos IV was captured and taken back to Alp Arslan’s camp as a prisoner. The other thirty thousand soldiers disappeared from history; in all likelihood they too were ambushed and slaughtered.

16

Alp Arslan, rubbing salt in the emperor’s wounds, treated him with honor, fed him from the sultan’s own table, and set him free—after extracting from him solemn vows of friendship and peace. Romanos, in a state of high embarrassment, began the journey back to Constantinople; just as the Battle of Manzikert had destroyed most of the Byzantine army, so the captivity and the oath had destroyed his reputation. Michael Psellus himself declared that Romanos’s young co-emperors, the sons of Constantine Doukas, had no obligation to let the humiliated ruler back into the city. A handful of trusted men, including members of the Doukas family, set off to intercept Romanos on his way home. They captured him, blinded him, and left him in a monastery to die.

17

Now the oldest son of Constantine Doukas, Michael VII, became senior emperor, an event marked by a second coronation in October 1071. But he ruled over a changed map. The sultan of the Seljuq Turks had established a new Turkish outpost in Asia Minor, in lands that had once been Byzantine: a vassal ruler, the sultan of Rum, presided over this new Turkish state. The Turks had rooted themselves into Asia Minor and intended to remain; the massacre of the army at Manzikert had made it impossible for the Byzantines to muster a force large enough to drive them out.

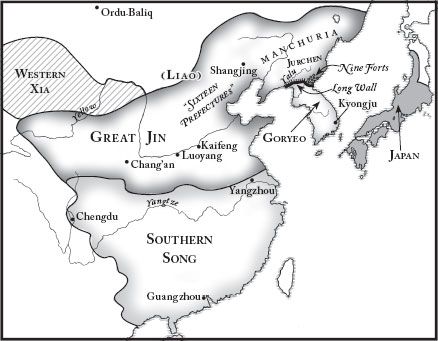

Between 1032 and 1172, the Jurchen sweep down from the north, and the Song are driven from the Yellow river valley

T

HE

S

ONG DYNASTY

had not lost its fascination for those on the outside. In 1032, the strongest outsiders lived in the kingdom of the Western Xia, and they had their eyes fixed on the wealth and culture of the Song.

The Western Xia had been nomads who wandered up from the south. Between 982 and 1032, their great chief Li Deming had managed to organize the tribal confederation into a state. He had ambitions to educate his son, Li Yuanhao, into a true monarch. Just before his death in 1032, Li Deming sent seventy horses as a gift to Song Renzong, asking for a copy of the Buddhist scriptures so that he could complete Li Yuanhao’s training.

1

Apparently the Song emperor ignored the request, because in 1035 Li Yuanhao, now ruler of the Western Xia state, asked for the scriptures again. This time, his envoy returned with the books. The volumes of Buddhist teachings helped to support Li Yuanhao’s efforts to become the emperor of a civilized nation rather than the warleader of a tribal confederation: to be a monarch as great as the ancient Chinese monarchs meant accepting the religion of the Chinese throne (even though the Buddhism held by the Song court did not stretch back nearly to the times of the semidivine Sage Emperors).

At Li Yuanhao’s public enthronement, carried out once the Buddhist scriptures were in hand, his ministers declared him to be Sage of Culture and Hero of War, like the emperors of the distant Chinese past. The title has survived because Li Yuanhao had thrown his energies behind the creation of a script for his native Tangut language, a complicated system based on Chinese principles; using the new lines and strokes, his chronicler recorded the details of his coronation. Li Yuanhao knew that without books of their own, his people would have no past. Without a past, they could never claim to be equal to the Song.

2

In 1038, he sent a letter to Song Renzong, demanding official Chinese recognition of his new status. The letter lists all of the reforms Li Yuanhao instituted in the Western Xia lands, including his creation of written language for the Tangut. It then gets to the point: “Now that the dress regulations have been completed,” he writes, “the script put into effect, the rites and music made manifest, the vessels and implements prepared…I was enthroned as Shizu, Originator of Literature, Rooted in Might, Giver of Law, Founder of Ritual, Humane and Filial Emperor. My country is called Great Xia, and the reign era is called ‘Heaven-Conferred Rites, Law, and Protracted Blessings.’ I humbly look to Your Majesty the emperor, in your profound wisdom and perfection, whose benevolence extends to all things, to permit me to be invested as the ‘ruler facing south’ in this western land.”

3

The polite request covered over steely determination. Thirty years earlier, the Song emperor’s father had been forced to recognize the Liao ruler as an emperor with status equal to himself, and now the Western Xia ruler wanted the same. Unlike the great dynasties of the past, the Song did not dominate the east. It was only one kingdom in a landscape of kingdoms; it was not notably more prosperous than its neighbors; but the Song emperor had something the northern and western kings did not. He had the sheen of millennia of tradition, and they wanted some of that gloss for themselves.

If he didn’t yield it, they were ready to fight for it. Song Renzong declined to bestow the title of emperor on the western upstart, and in 1038, the Western Xia army invaded. Thirty years of peace had softened the Song border troops. One chronicler notes that less than half of the soldiers were still able to draw the heavy crossbows used in battle, and almost none of the officers or troops had combat experience.

4

Between 1038 and 1042, the Western Xia overran the forts along the western frontier. Li Yuanhao advanced his men cautiously, not attempting to capture more of the difficult rocky terrain than he could defend. Slowly the western reaches of the Song were eaten away, and in 1042 the situation grew worse when the Liao to the north demanded another chunk of Song territory for themselves. Song Renzong offered to increase the annual tribute instead; this avoided a two-front war but drained the Song treasury even further.

5

By 1044, he had decided to make peace. He still refused to recognize the Western Xia ruler as a real emperor, but he paid out yet more annual tribute to buy a truce. Li Yuanhao agreed to the compromise. Six years of fighting had stressed his own army, and even though he had failed to get the legitimization he craved, the money was an effective salve to his wounded personal pride.

The Song, meanwhile, had turned their attention back towards military matters. Apparently the war with the Western Xia had forced the Song generals to scramble for information; by 1044, the last year of the war, a band of scholars commissioned to put together a compendium on techniques of war had finished their work. The volume,

Wujing Zongyao

, describes a pump-powered flame-thrower that could hurl naphtha, the same “Greek fire” used by the defenders of Constantinople; it also explains how to make explosive black powder from coal, saltpeter, and sulfur, the first time in history that the formula for gunpowder appears in writing.

The purchased truce lasted for some time on both the northern and western borders, giving the Song time to rebuild their military might. Song Renzong raised taxes to pay for the tribute as well as a newly expanded national army. He also ordered new standards put into place for new army recruits. They would have to pass an eye exam, as well as tests in running, jumping, and shooting. This time, the temporary peace would be used to prepare for the next war.

6

T

HE PEACE LASTED

for almost fifty years. The Liao had earned official imperial recognition from the Song empire, along with cash payments; the Western Xia had received only the cash but had decided to be content.

And then another tribe, making the same journey from nomadic wanderings to settled empire, blew in from the north at the beginning of the twelfth century and swept down onto the settled kingdoms. They were the Jurchen, tribes who spoke a language distantly related to the Turkish tongues. They lived mostly on the wooded plains north of Goryeo, in the lands later called Manchuria; some of the western groups had come under the rule of Liao and were known as the “Civilized Jurchen,” but the eastern bands were still free and wild. The Song and Liao courts called these the “Raw Jurchen,” and they roamed beyond the control of either emperor.

7

Late in the eleventh century, one of the eastern Jurchen clans, the Wanyan, began to conquer its Jurchen neighbors—the first clear step on the path to nationhood. Some of the Jurchen under attack fled south into Goryeo.

Since the days of its founder Wang Kon, the kingdom of Goryeo had declined to chase after the Song stamp of approval. It had fought its own border wars against the Liao, who made periodic attempts to expand into Goryeon territory, but a great border war in 1018 had shattered the Liao army, and since then the two countries had been more or less at peace. Until now, the nomadic Jurchen to the north had been more of an annoyance than a military threat: “The people of the northeast frontier frequently suffered from the Jurchen horsemen who came to invade and rob,” remarks the contemporary chronicler Choe Seung-no. To keep them out, the eleventh-century kings of Goryeo built a Long Wall that stretched from the mouth of the Yalu river, over three hundred miles inland.

8

The wall was effective against random wanderers, but it didn’t stem the flood of refugees from other Jurchen tribes, fleeing from the ambitious Wanyan. When the Wanyan demanded that the refugees be returned, the Goryeon general Yun Kwan led a special army, “The Extraordinary Military Corps,” north to fight against them.

Unlike the regular Goryeon army, which was largely made up of foot-soldiers, the Extraordinary Military Corps had a full division of cavalry, which was more effective against the mounted Jurchen. In 1107, the Extraordinary Military Corps pushed its way into Jurchen territory and built a series of defensive positions known as the Nine Forts in order to protect the northern territories.

9

In 1115, the Wanyan clan of the Jurchen came under the rule of a younger brother named Akuta, and their fortunes began to change. Akuta realized the need for ceremonial kingship, for an established bureaucracy, for a history—for all the things that, time and time again, had turned wandering nomads into a settled state. Like every other aspiring king on the northern plain, he wanted the Song stamp of approval, but he was willing to work up to it. Instead he sent a message to the Liao emperor, demanding that the

Liao

extend the formal recognition that Akuta was a Great Holy and Enlightened Emperor. He wanted his clan to be known, from now on, by the Chinese name “Great Jin” he intended to wear royal robes and ride in a jade-encrusted carriage, and (incidentally) he wanted the Liao to pay an annual tribute, almost as large as the tribute the Song paid to

them

.

10

The Liao resisted, and the Jurchen attacked. With short-sighted enthusiasm, the Song emperor Huizong agreed to make an alliance

with

the Jurchen

against

the old northern Liao enemy. Song Huizong was not a military man; he had been on the throne since 1100 and spent much less time governing than he did building Taoist temples, endowing Taoist monasteries, and studying Taoist teachings.

In this he was encouraged by the flattery of a self-centered Taoist priest named Lin Lingsu, who assured the emperor that he was the incarnation of the supreme deity “Great Imperial Lord of Long Life.” This convinced Huizong that he was indeed a Son of Heaven, possessor of the Divine Mandate; and he occupied his days with painting, poetry, tea ceremonies, and Taoist rituals.

11

He was swayed into the alliance with the Jurchen when Akuta promised that after the joint conquest of the Liao, the Song could reclaim the southern reaches of the old Liao empire: this land had once been the Chinese “Sixteen Prefectures,” and it had been in enemy hands for a century. Retaking the Prefectures would shore up the Divine Mandate with a real display of victory. So Huizong sent his army to help conquer the Liao, paying no mind to the expanding power of the Jurchen themselves. In 1122, the combined armies reached the Liao capital and took the emperor captive; the remains of the Liao army and a hundred thousand refugees fled west, away from the conquerors.

12

But the Jurchen refused to hand over the Sixteen Prefectures. Akuta had died, and had been succeeded by his young brother, who took the Chinese name Jin Taizong; but probably neither brother had ever intended to follow through on the promise. Instead the Jurchen marched into Song territory, heading for the Song capital of Kaifeng.

Under Song Huizong’s rule, the carefully built system of trained local militia had fallen to bits, and the Jurchen broke through the Song defenses with little difficulty. By the end of 1125 they had crossed the Yellow river and were in sight of the city.

Song Huizong, jolted out of his overconfidence, tried to escape from responsibility for the looming defeat by faking a stroke, abdicating, and ordering the royal robes placed on his heir, his twenty-five-year-old son, Qinzong. Qinzong refused to take on the thankless job; when the robes were draped on his shoulders, he pushed them off and told his father that to accept them would be disloyal and unfilial. Huizong, who was pretending that his right side was paralyzed, wrote a message with his left hand ordering his son to take up the Mandate. “He still strongly declined,” says one account, so

Huizong ordered the eunuchs to forcibly carry him to Blessed Tranquility Hall and put him on the throne. Qinzong was definitely unwilling to walk, so the eunuchs forcibly carried him. He struggled with them and passed out from holding his breath. After he recovered they resumed carrying him to the western chamber of Blessed Tranquillity Hall, where the grand councilors met and congratulated him.

13

The Jurchen carried out their conquest of Kaifeng over several stages (demanding tribute, withdrawing, returning and demanding hostages, withdrawing), but by 1127 the game was over. The city was no longer able to hold out, and the Jurchen stormed its walls and began to steal treasure, food, animals, and women.

Song Qinzong, whose reign had not been one of courageous nobility, rounded up the daughters of the common people so that the Jurchen would rape them first, but the invaders soon broke into the houses of the nobility as well. The city was looted, burned, and then placed under enemy rule. Both Song Qinzong and his father were captured and taken, along with scores of other prisoners, back to the north. Huizong died in prison not long afterwards, but Qinzong lived for the next three decades in captivity.

14

The Song era was over. Refugees from the Song court fled their city, taking with them Qinzong’s younger half-brother Gaozong. They proclaimed him emperor in exile at Lin’an, far to the south. The Song had ended; the dynasty that would rule in the south for the next century was called the “Southern Song,” but it was only a weak remnant of previous glories.

*

Even worse, the northern land that now lay in Jurchen hands was the cradle of Chinese culture, the valley where the most honored of its divine kings had lived, the home of the great deeds that had made the ancient Chinese empire the envy of its nomadic neighbors. The poems of the Southern Song are filled with longing for the abandoned lands: