The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (50 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

Rather than executing Desiderius, Charles imprisoned him in a monastery in northern Francia. Desiderius’s son and heir fled to Constantinople, where he took refuge at the imperial court. Charles, at twenty-seven, was now the king of all the Franks and Lombard Italy as well. In 774, he claimed the traditional Iron Crown of the Lombards (so called because the Lombards believed that the iron band inside it was beaten from one of the nails from Christ’s cross), and the Lombard kingdom ceased to exist. It was the first of the great, empire-expanding victories that would earn him the name Charles the Great or “Charlemagne.”

Exalted by his victories in the northeast and southeast, Charlemagne then set his sights on the southwest.

Abd ar-Rahman’s seizure of the Emirate of Cordoba had not sat well with all of the Muslims in al-Andalus. In 778 a group of dissidents in the northeastern part of al-Andalus, led by the chief administrator of the region, Sulayman al-Arabi, invited Charlemagne to help them get rid of the Umayyad rule. They promised him that the city of Zaragoza, well inside the borders of the emirate, would open its gates and welcome him in so that he could use it as his base of operations.

This must have seemed like a good idea, but it ended in disaster. Charlemagne marched to Zaragoza with his men, visions of conquering al-Andalus in his head. When he arrived at its walls, however, the governor of the city—who had up until this point been in alliance with Sulayman and the dissidents—changed his mind and refused to let him in. Charlemagne camped outside the walls for weeks, but the gates never swung open. Without a walled city to protect him, he was finally forced to withdraw back through the Pyrenees. He was furious, and on the way home he sacked the fortress of Pamplona as he passed it.

This, like his destruction of the Irminsul, was a miscalculation. Pamplona was not firmly in the control of the emir of Cordoba. It was instead the home of the Vascones, a tribe that had been in Hispania before the Romans arrived and had survived in the mountains through the Roman occupation, the Visigoth takeover, and the arrival of the Arabs.

*

They were tough, independent, and resourceful, and they took vengeance on Charlemagne as he went back through the mountains towards his own kingdom. At the Pass of Roncesvalles, the Vascones attacked the end of the Frankish column, wiping out the baggage train and killing the rear guard “to the last man.” They were lightly armed and experienced in the mountains, and after the slaughter they disappeared into the rough terrain. The Franks, weighed down by their own weapons and armor, were unable to pursue them.

12

The ambush was disproportionately devastating to Charlemagne, because a number of his officers and personal friends were in the rear when the Vascones descended. Among them was a man whom Einhard calls “Roland, Lord of the Breton Marches”—the nobleman who governed the Frankish territory on the western coast, just above the mouth of the Loire. Stories were told about the minor ambush until it had been transformed into a pivotal battle; Roland became the hero of the first French epic, the twelfth-century

Song of Roland

, which turns the bloody incident into a major conspiracy between the Arabs of Zaragoza and a traitor within Charlemagne’s own camp. In the epic, four hundred thousand Arabs descend on the rear of the Frankish army, and Roland refuses to blow his horn for help until he has fought to the end of his strength. When he finally does blow the horn, Charlemagne rides back from the front of the column to help, but the force of the horn’s sound has shattered the bones of Roland’s skull.

Charlemagne then takes vengeance on the Arabs, with the help of God:

For Charlemagne a great marvel God planned:

Making the sun still in his course to stand.

So pagans fled, and chased them well the Franks

Through the Valley of Shadows, close in hand;

Towards Sarraguce by force they chased them back

And as they went with killing blows attacked.

13

But in reality, the Battle of Roncesvalles ended Charlemagne’s ambitions in al-Andalus. He never pushed his way past the Pyrenees again.

Between 751 and 779, the Brilliant Emperor falls in love with his son’s wife, and loses her, along with his throne

W

HEN

G

AO

X

IANZHI

arrived back home after the Battle of Talas, he discovered that his emperor was in trouble.

Tang Xuanzong had been on the throne for forty years, leading the Tang into the most brilliant era of its existence. The empire was at the very height of its power and size. The arts flourished. Tang porcelain, as clear and thin as glass, was prized by every country that bought goods from the trade route that stretched from China toward the west: the Silk Road. The Tang painter Wu Daozi created portraits and murals so breathtaking that he was rumored to have opened a painted door in one of his landscapes and stepped through. Tang poets composed verses that would endure for centuries. Li Bai, whose reputation had spread empire-wide, wrote in the new “regulated” style, orderly and metered:

Cut water with a sword, the water flows on;

Quench sorrow with wine, the sorrow increases,

In our lifetime, our wishes are unfulfilled.

1

Wang Wei, poet and painter, wrote

jueju

, “cut-short” quatrains that glanced at a truth and then away, leaving the reader to seek the deeper meaning.

A morning shower in Weicheng has settled the light dust;

The willows by the hostel are fresh and green;

Come, drink one more cup of wine,

West of the pass you will meet no more old friends.

2

But the flowering of the arts at court could not disguise the rot at its roots. The Brilliant Emperor, now nearing seventy, had become obsessed with his son’s young wife Yang Guifei. He had forced his son to divorce her and had taken her for his own consort. Her cousin, the official Yang Guozhong, had been given more and more power at court through her influence; she was fond (perhaps overly fond) of the army officer An Lushan, and the Brilliant Emperor pliantly awarded An Lushan greater and greater authority. He had dismissed his chancellor Zhang Jiuling, a man who had gained his position through examination (he was famous for his wisdom, his asceticism, and his stern moral compass; he once gave the emperor advice, rather than a present, for his birthday), and in his place had appointed the dictatorial, privileged aristocrat Li Linfu.

3

And the expansion of the empire had not come without cost. Resentment was building over the extensive military campaigns that the Brilliant Emperor ordered. “White bones are the only crop in these yellow sands,” wrote Li Bai, after one protracted war against the northern barbarians,

There seems no end to the fighting.

In the wilderness men hack one another to pieces,

Riderless horses neigh madly to the sky….

The blood of soldiers smears grass and brambles;

What use is a commander without his troops?

War is a fearful thing—

And the wise prince resorts to it only if he must.

4

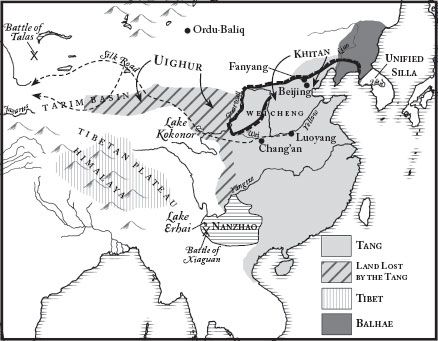

The emperor’s growing preoccupation with his personal life meant that the generals on the frontiers took more and more authority themselves, even as wars multiplied. In 751, while Gao Xianzhi was struggling with the Arabs to the far west, the Khitan invaded the north once again and a year-long struggle to drive them out began. The peace with Tibet disintegrated, and Tibetan attacks and raids on the central Asian frontier intensified.

At the end of that same year, a southwestern tributary kingdom of the Tang rebelled. The Nanzhao kingdom had coalesced in the land around Lake Erhai, out of six tribes known to the Chinese as the Bai. As with so many other newborn nations, this one could trace its existence back to the conquering instincts of a single personality: the Bai chief Piluoge. Twenty years earlier, Piluoge had not only claimed the rulership of all six tribes, but also burnt the chiefs of the other tribes alive. His rise had been so meteoric that, barely a decade after seizing power, he had managed to make a match between his grandson and a princess of Tang descent.

The Brilliant Emperor had seen Piluoge’s strengthening domain as a useful buffer between the Tang border and the hostile soldiers of Tibet, and had bestowed a title on Piluoge; he even invited the new king and his grandson to come and celebrate the marriage in Chang’an itself. But Piluoge’s successor Geluofeng now took advantage of the weakness he saw in the Tang and went on the attack. The Tang governor of the southwest territories sent an army to respond, but Geluofeng and the Bai army handed them an unexpected and embarrassing defeat.

5

50.1: New Kingdoms and the Tang

*

A few months later, the aristocratic minister Li Linfu died, and the consort Yang Guifei used her influence to have her cousin Yang Guozhong appointed as next chancellor of the Tang. This was not a bad thing; Yang Guozhong was ambitious and not averse to working his family connections for his own gain, but he was also loyal to his emperor. Once admitted to the inner workings of the government, he grew increasingly worried about his cousin’s marked preference for the general An Lushan. In his opinion, An Lushan was not only ambitious, but unprincipled, and he feared that the general was plotting against the throne.

6

In 754, a second victory by the Nanzhao gave the general An Lushan his chance. A large Tang force under another general had been sent south to punish Geluofeng for daring to defeat the southwest border force, but at the Battle of Xiaguan, the Tang army was massacred. Almost all of the survivors were killed by plague as they limped home. It was said that two hundred thousand soldiers died fighting the small southern kingdom, and this merely heightened the anger and discontent of an army that had already been embarrassed by the defeat at the Battle of Talas three years before.

In 755, An Lushan declared himself an open rival to the Brilliant Emperor, with a royal capital of his own at Fanyang, the northern military garrison where his command had been centered for some years. He commanded over a hundred thousand men, a mixture of well-trained soldiers and northern horsemen recruited from the Khitan. They followed him south along the Yellow river to the fortress at Luoyang, a center of administration for the east of the empire, which they captured without difficulty. Here, An Lushan lingered, resting his army and preparing for an attack on Chang’an itself.

7

The Brilliant Emperor was furious. He gave Gao Xianzhi, commander at the Battle of Talas, the task of campaigning against An Lushan—and, when the veteran general did not meet with quick success, had him beheaded. In order to pacify the emperor, the loyal chancellor Yang Guozhong then planned an enormous frontal assault—against the advice of military advisors who recommended circling the rebel forces, cutting them off from the supplies and reinforcements coming from Fanyang, and waiting them out.

In the summer heat of July 756, six months after the fall of Luoyang, the Tang royal army marched to meet the rebels and was destroyed. One hundred and eighty thousand men fell, leaving no one to defend Chang’an itself. The Brilliant Emperor and the chancellor fled to the west. Ten days after the battle, An Lushan arrived at the walls of the capital and occupied it, almost unopposed.

On the road into exile, the Brilliant Emperor’s royal guard turned on the chancellor. They blamed him for the disaster, and despite the emperor’s objections, they surrounded and murdered both Yang Guozhong and his son. Then they demanded that the Brilliant Emperor hand over his consort, the beautiful Yang Guifei, for execution. She had helped Yang Guozhong rise to power; in their eyes, her partiality both for her cousin and for the rebellious An Lushan had helped bring Tang power down.

The emperor stalled, objected, refused, and then finally realized that he had no choice. Rather than handing her over to the angry soldiers, he ordered one of his loyal court eunuchs to kill her quickly. His grief was made famous, half a century later, by the poet Bai Juyi:

Covering his face with his hands,

He could not save her.

Turning back to look at her,

His tears mingled with her blood.

Yellow dust filled the sky;

The wind was cold and shrill….

Heaven and earth may not last forever,

But this sorrow was eternal.

8

The Brilliant Emperor retreated to the southern city of Chengdu, mourning all the way.

The An Lushan rebellion ended badly for both the Brilliant Emperor and for the rebel An Lushan. The emperor’s son Suzong, the heir apparent, forced the old broken emperor to abdicate in 756 and claimed the throne (in exile) himself. Meanwhile, in Chang’an, An Lushan had declared himself the emperor Yan. But he had contracted some disease that caused him to suffer from large and excruciatingly painful boils on his face, and he was growing increasingly short-tempered and paranoid. After months of unpredictable and cruel behavior, he was murdered in the middle of the night in 757 by one of his house servants.

9

An Lushan’s son picked up his banner, but Tang Suzong managed to re-enter Chang’an with his own soldiers later in the same year and drive the remaining rebels out. This didn’t end the fighting, though. Resistance continued for the next six years, in a long-drawn-out series of inconclusive battles. Tang Suzong died of a heart attack in 762, and his son Tang Daizong finally managed, in 763, to put down the last remnants of the An Lushan rebellion.

10

But the internationally feared power of the Tang was broken. Almost all of the border guard had been recalled to fight on one side or the other of the civil war, and the frontiers of the empire had begun to crumble. In late 763, while the new emperor Tang Daizong and his general were in Luoyang mopping up the remnants of rebellion there, Tibetan troops whirled all the way into Chang’an and looted it before withdrawing. For the next decade, Tibetan attacks from the southwest would be an annual event.

11

To the north and northwest, the Tang border suffered just as badly from the incursions of Uighur tribes. The Uighurs had been a vassal tribe of the Eastern Turkish Khaghanate, but they had broken away from their overlords and established their own kingdom, with its capital at Ordu-Baliq. Both Tang Suzong and his son Tang Daizong had hired Uighur mercenaries to help fight against the rebels, and the heavy payments that the emperors handed over had boosted Uighur wealth. The mercenaries had taken some knowledge of Chinese writing back home with them (along with loot stolen from both Chang’an and Luoyang), and this became the basis of a Uighur writing system; the imported culture sparked a transformation that gradually turned the tribes of warrior nomads into a more stable kingdom.

12

To the northeast of the empire, the Korean kingdom of Unified Silla, which now dominated most of the peninsula under the rule of King Gyeongdeok, felt the sting of the Tang civil war. The kings of Silla had gained their unified empire with the help of Tang forces, and they needed Tang support because their power over the peninsula was not unchallenged. Survivors of the destroyed Korean kingdom of Goguryeo had gathered in the north, where they had settled and intermarried with the semi-nomadic tribes of the Malgal and formed a new kingdom called Balhae. In the aftermath of the An Lushan rebellion, the Balhae king Mun took advantage of the lessened Tang presence to conquer the surrounding territory, until Balhae had grown even larger than Unified Silla to its south.

13

With so much fighting going on at the borders, the population of the Tang empire shifted away from the north and west, towards the central and southern lands. The ancient cities of the north fell into decline. By the time Tang Daizong died in 779, the Tang had lost all of its holdings in central Asia. The trade routes to the west had been disrupted and blocked. The generals who were tasked with protecting the shrunken outer reaches of the empire gained more and more power; neither the Tang emperor nor his ministers were able to check their growing independence. The surrounding peoples—Tibet, Nanzhao, the Uighurs, Balhae, Unified Silla—had shifted and changed. The An Lushan rebellion had reshaped not just Tang China, but the political landscape of the entire continent.

14