The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (52 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

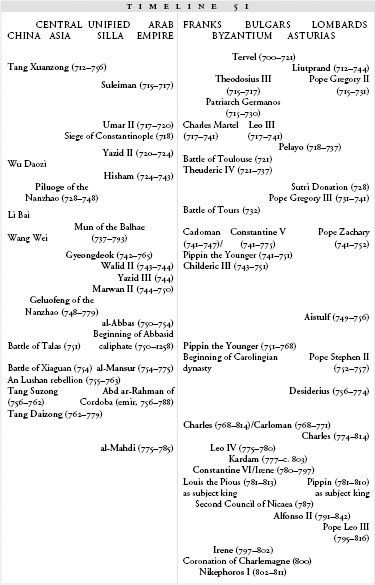

51.1: The Empire of Charlemagne

But whether or not Leo was guilty was almost a side issue. The

position

of the bishop of Rome had to be unassailable. If the pope spoke for God, he could not be removed by the same sorts of earthly machinations that had brought Constantine VI to a wretched end. Yet in order to protect the office of the papacy from becoming another throne to be contested and won by force, Constantine would have to exercise force on its behalf.

He delayed taking action, thinking the problem through. Ultimately, it seems, his advisor Alcuin swayed his mind, pointing out that Charlemagne was now the only remaining representative of God in the known world who still had any power to right wrongs.

There have hitherto been three persons of great eminence in the world, namely the Pope, who rules the see of Peter…and you have kindly informed me what has happened to him. The second is the Emperor who holds sway over the second Rome—and common report has now made known how wickedly the governor of such an empire has been deposed…. The third is the throne on which our Lord Jesus Christ has placed you to rule over our Christian people, with greater power, clearer insight and more exalted royalty than the aforementioned dignitaries. On you alone the whole safety of the churches of Christ depends.

15

As the last protector of the church, Charlemagne’s duty was clear.

So, in 800, Charlemagne sent the pope home to Rome with an armed bodyguard. He followed, marching “in full martial array,” with his army into the city. When he arrived, Leo put his hand on the copy of the Gospels in St. Peter’s Cathedral and swore, in the presence of onlookers, that he was guiltless of any wrongdoing. With Charlemagne and his soldiers standing by, the oath was effective.

16

Charlemagne lingered in the city until Christmas Day. He went to morning mass, knelt for the prayers, and as he began to get to his feet, Leo III came forward and put a gold crown on his head. The crowd, which had been coached, cheered: “Long life and victory to Charles, the most pious Augustus, the great, peace-loving Emperor, crowned by God!” He had been crowned

imperator et augustus

, two titles that belonged to the emperor of Rome—titles that, in the eyes of the Byzantine court, had long ago been transferred to Constantinople.

17

But in the eyes of Charlemagne, the title of emperor had been unclaimed until his coronation. The official description of the event, written afterwards by a Frankish cleric, explains, “When, in the land of the Greeks, there was no longer an emperor and when the imperial power was being exercised by a woman, it seemed to Pope Leo himself and…to the whole Christian people, that it would be fitting to give the title of emperor to the king of the Franks, Charles.”

18

Charles’s biographer Einhard claims that Charlemagne knew nothing about the plan to crown him and denied ever wanting the imperial title. But he is the only writer who assumes such massive ignorance on the part of the sharp-minded and wary king. The crowning on Christmas Day was simply a formal recognition of an authority that Charlemagne had been claiming for some time: the authority to stand as the protector of faith, guarantor of civilization, and highest civil power in the Christian world.

In Constantinople, the coronation was scorned as meaningless. But Irene was not in a good position to defend herself as the true protector of the faith and guarantor of civilization. Her rule had been chaotic, murderous, and ineffective. In 802, her finance minister led a coup against her and removed her from the throne. He forced her to go into exile within the walls of a monastery she had built herself, and was crowned emperor in her place as Nikephoros I.

19

The following year, Nikephoros I approached Charlemagne by way of ambassadors and suggested a treaty that would protect the city of Venice, still Byzantine-loyal, from Frankish occupation. Eventually the two men came to an agreement, the

Pax Nicephori

. Nikephoros I and Byzantium would keep control of Venice and its important port. In return, Charlemagne would receive a generous annual payment.

The terms made it very clear that this was a treaty between equals. But in signing it, Nikephoros I gave himself the imperial title, yet refused to call Charlemagne “Emperor.”

Between 786 and 814, Abbasid merchants spread across the west, Charlemagne becomes Protector of the Faith in Jerusalem, and the Bulgarian khan Krum nearly brings Constantinople down

T

HE

A

BBASID CALIPH

Harun al-Rashid was more willing than Nikephoros I to court Charlemagne’s goodwill. As an Abbasid ally, Charlemagne could not only halt Byzantine expansion to the west but also help guard Abbasid interests against the breakaway Umayyad realm in al-Andalus, the Emirate of Cordoba.

Those interests had more to do with trade routes than with conquest. Harun al-Rashid had been elevated to the caliphate in 786, after the death of his father, al-Mahdi, and very soon had earned himself the nickname “The Righteous.” One of his first acts as caliph was to lead the annual pilgrimage to Mecca in person, and when he arrived in Arabia he gave enormous money gifts to the leaders of both Mecca and Medina. “Through Harun, the light has shone forth in every region,” declared one of his court poets, “and the straight path has become established by the justness of his conduct. He is a leader whose greatest concern is with raiding the infidels and the Pilgrimage.”

1

In actuality, al-Rashid was more interested in trading than raiding. He did not completely neglect the ongoing war with Byzantium, but during the first fifteen years of his caliphate he was more concerned with security and prosperity than with conquest; most of his energies went into establishing and guarding trade routes. Ten years after his accession, he moved his court from Baghdad to Ar Raqqah, which was closer to the northern trade routes into Khazar territory. Thanks to a semi-peace with the Khazar khan, Arab merchants were now able to travel up north through the Caspian Gates (the pass through the mountains just west of the Caspian Sea) to the Volga river, where they could trade not only with the Khazars but also with Scandinavian merchants. By the eighth century, adventurers from the northern Scandinavian kingdoms had crossed the Baltic Sea and built little trading posts southward along the rivers that reached down into Europe; they offered furs, exotic and luxurious to the Arab buyers, and they wanted gold and silver coins, which were scarce in their own lands.

2

Al-Rashid’s care for the trade routes meant that the Arab hand reached into far distant lands that had remained untouched by conquest. Embassies between Charlemagne’s court and al-Rashid’s imperial palace at Ar Raqqah travelled back and forth; the Arab ambassadors took the sea route from the Mediterranean coast, south around Italy and up to the port city of Genoa, and then travelling north to Charlemagne’s court at Aachen (his newly chosen capital city). With the ambassadors, al-Rashid sent gifts: a water-driven clock, a chess set, spices, and an albino elephant named Abu’l-Abbas, which had been captured from an Indian king. Charlemagne liked the idea of a war elephant. He took it on campaign with him when he had to fight against invading Scandinavians to the north, which undoubtedly startled them.

3

Al-Rashid’s coins ended up even farther away than his elephant. Sometime around the turn of the century, one of his merchants paid a gold dinar into the hands of a Scandinavian trader, who took it north and used it to buy goods from an Anglo-Saxon merchant, who sailed home with the coin and landed at a port in the English kingdom of Mercia. Mercia, which by this point had expanded to cover a good bit of the southeast of England, was under the rule of King Offa, a Christian monarch who considered himself almost equal to Charlemagne in dignity.

*

Offa even suggested, by way of diplomatic correspondence, that his son and heir should marry one of Charlemagne’s daughters—which Charlemagne found so presumptuous that he closed Frankish ports for a while to Mercian ships.

4

Once in Mercia, the merchant used the coin to buy a night’s lodging from an innkeeper, who later that year used it to pay the king’s tax-collector. And so it came into the hands of Offa’s silversmith, who was mulling over the designs for the next year’s English coinage. He liked the pretty patterns on al-Rashid’s gold dinar and decided to copy them. The following year, the coins of the English monarch were minted with “OFFA REX” written on one side and, the Arabic words for “There is no God but Allah, and Muhammad is his prophet” on the other. The silversmith, of course, had no idea what the words said; “OFFA REX” is written right side up, but the Arabic letters are all upside down.

5

Back in Ar Raqqah, enriched by trade with such far-flung lands (and also by his practice of confiscating the goods of his wealthy subjects when they died), al-Rashid grew richer and richer. His splendor was so great that it became legendary. Less than two generations after his death, tales were already weaving themselves around him. Within a century, these tales would begin to take shape as the sprawling

Arabian Nights

: a thousand and one nights’ worth of stories about thieves and heroes, courtesans and queens, with Harun al-Rashid and his jester at the center of the adventures.

6

52.1: Coin of Offa of Mercia, showing inverted Arabic inscription copied from an Abbasid dinar.

Credit: © The Trustees of the British Museum/Art Resource, NY

Al-Rashid was also careful with the empire’s defenses. He fortified the eastern borders of the empire by making an alliance with the Tang emperor, Tang Shunzong, in order to check the power of the Tibetans, who threatened to push into Arabic land near the Oxus river. He defended the western borders by authorizing ongoing raids into Byzantine land, finally forcing Nikephoros I to hand over a sizable annual tribute in order to keep the peace: three hundred thousand dinars, which worked out to around a ton and a quarter of gold added to the caliph’s treasury each year.

*

In 807, al-Rashid granted Charlemagne yet another proof of the Frankish king’s high place in the Christian hierarchy. He agreed to make a decree that protected the Christian holy sites in Jerusalem, which was under Arab governance: Christian pilgrims would be allowed, without restriction, to visit the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (said to stand on Golgotha, the hill of the Crucifixion), the Via Dolorosa (“way of suffering,” the path taken by Christ on the way to his death), and the other landmarks of their faith. It was a decree that would naturally have been sent to the pope, the spiritual father of all Christians. But al-Rashid directed his pledge to Charlemagne and promised special treatment for Frankish pilgrims in particular.

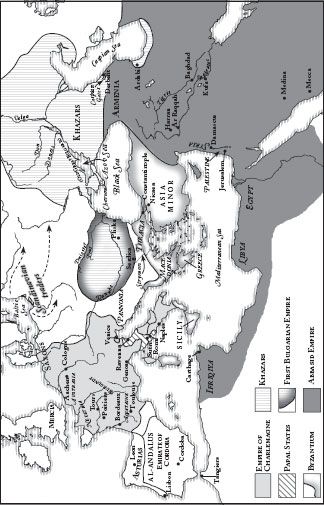

52.1: Expansion of the First Bulgarian Empire

At the same time, the bishop of Jerusalem sent two monks to Aachen so that they could present Charlemagne with the key to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre itself. Even though the pope himself had crowned Charlemagne as Protector of the Faith, these must have been sharp-edged little pills for Leo III to swallow.

7

Meanwhile the emperor of Constantinople, Nikephoros I, had been given little leisure to complain about Charlemagne’s usurpation of his role as emperor of the Romans. He was too busy worrying about the khan of the Bulgarians, who had rocketed (without much attention paid to him by contemporary historians) into a position as one of the great rulers of the west.

The Bulgarian khan was named Krum, and under his rule—which began sometime between 796 and 803—Bulgaria swelled into a major power. Krum’s southern territories lay directly against the Byzantine border, and Constantine VI’s disastrous attempt to defy the Bulgarian khan Kardam, Krum’s predecessor (and possibly his uncle), had clearly revealed just how vulnerable the Byzantine territory now was.

8

Nikephoros knew this. Around 805, Krum invaded the territory of the once-great Avars and folded it into his own, which brought his empire directly to the eastern border of Charlemagne. Deciding not to wait until Krum became even more powerful, Nikephoros declared war on the Bulgarians and began to arm his troops.

It took him over a year to get the troops on the road, partly because he had to put down a palace rebellion in the middle of his preparations. But by 808, he was moving troops into the Strymon river valley, on the southern Bulgarian border. Krum’s men descended on them before they were at full strength and drove them back, killing a number of soldiers and officers and (even more damaging) capturing all of the money Nikephoros had sent along with his generals to use for payroll—eleven hundred pounds of gold, according to Theophanes.

9

Hostilities now began in earnest. In 809, Krum led his army against the city of Serdica, a frontier city within Byzantine territory, and captured it, slaughtering six thousand Byzantine soldiers and hundreds of civilians. Nikephoros did not handle the defeat well. The officers who had escaped the massacre, afraid that they would be blamed and executed, sent him a message asking for immunity. When he refused, they all deserted and joined the Bulgarian army.

10

It took Nikephoros I (who was again distracted by yet another rebellion at home, this one brought about by his decision to raise everyone’s taxes) more than a year to prepare his army for a return attack. He had decided that the only appropriate response was to wipe Krum out entirely, and to that end he imported soldiers from Thracia and Asia Minor to beef up the depleted forces at Constantinople. In 811, the Byzantine army marched towards Krum’s headquarters at Pliska, just west of the Black Sea.

11

At first, Krum’s defenders were defeated and pushed backwards as the Byzantine army advanced. Alarmed by the ferocity of the approaching troops, Krum decided to abandon Pliska. Nikephoros arrived at the Bulgarian capital on July 20, at the head of his army, and ordered his men to slaughter the population, take the goods, and burn the place down: “He ordered that senseless animals, infants, and persons of all ages should be slain without mercy,” Theophanes writes. He finally had the upper hand, and he refused to listen to a message from Krum suggesting a treaty.

12

But Krum was not finished. He had retreated, along with every man he could recruit, into the mountains through which the Byzantine army would have to march on their way home, and had built a wooden wall across the pass. On July 25, heading for Constantinople in triumph, Nikephoros and his men ran directly into the wooden wall. The Bulgarians attacked the trapped army as it piled up in front of the barrier. Nikephoros, fighting at the front, was killed almost at once. Soldiers who tried to climb the wall and escape fell into an enormous ditch that the Bulgarians had dug on the other side and filled with burning logs.

13

The Byzantine troops were slaughtered. Krum turned out to be no more gracious in victory than his opponent. He beheaded the emperor’s corpse, stuck the head on a pole, and—once the flesh had rotted off—had the skull coated in silver so that he could use it as a drinking goblet.

Meanwhile, Nikephoros’s son and second-in-command, Staurakios, had escaped, badly wounded by a blow to his spine. His companions hauled him back to Constantinople, where he was crowned emperor in his father’s place while lying on a litter. But Staurakios’s wound proved incurable. He sank into paralysis, and by October was forced to give power over to his brother-in-law Michael Rangabe. Early the next year, Staurakios died. For months, he had suffered from pressure ulcers on his back, and the wounds turned gangrenous: “No one could bear to approach him because of the foul stench,” Theophanes writes.

14

Krum suggested to Michael Rangabe that it was time for a truce, but even when the Bulgarian king began to approach Constantinople—by early 812, most of Thracia was in Bulgarian hands—the new emperor refused to come to terms. Krum was the second (or perhaps third) most powerful sovereign in Europe for a time, but his skull-goblet represented a world of savage barbarity. In Michael Rangabe’s eyes, Krum was a khan, not a king; a wild man, not an equal; a barbarian, not the ruler of a western kingdom. In such a strait, Michael Rangabe decided that it would be more palatable to make his treaty with Charlemagne. The Frankish king might be presumptuous, but he was Christian, and the Franks were at least two centuries past dismembering enemies and using their body parts for tableware.