The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (35 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

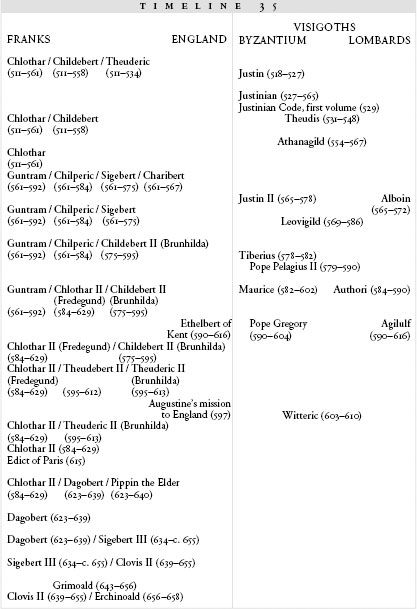

Between 589 and 632, a North African becomes emperor, the Persians besiege Constantinople, and new kingdoms of Slavs and Bulgars appear

W

HILE

G

REGORY THE

G

REAT

was coping with the Lombards, the Byzantine emperor Maurice was dealing with the Persians—an ever-present challenge that continually distracted him from the plight of his remaining lands in the west.

The first part of his reign had been complicated by Khosru’s son and successor Hurmuz, an ambitious and aggressive young man who spent over a decade battering the Byzantine frontier. The war had been long, dirty, painful, and expensive, and Maurice was tired of it. Nor had the war been popular with the Persians; the Persian army had not made any real or permanent gains, and the nobles at the court in Ctesiphon were embarrassed by the stalemate. Hurmuz had alienated them even further by trying to woo the Christians in Persia (“Just as our royal throne cannot stand on its two front legs without the two back ones,” he had told the Zoroastrians at court, “our kingdom cannot stand or endure firmly if we cause the Christians to become hostile to us”).

1

Finally one of Hurmuz’s generals revolted against his king. His name was Bahram Chobin, and he had earned a great reputation for himself by beating off a Turkish invasion on the far eastern border. Hurmuz, hoping for victory, had then dispatched him to the Byzantine frontier to press the war against Maurice, but in 589 Bahram lost a battle on the banks of the Araxes river to Byzantine forces. Hurmuz was furious. He sent his general a dress to wear, along with an insulting letter dismissing him from command.

2

Bahram refused to give up his post, so Hurmuz sent troops to remove him by force. The troops promptly defected to Bahram’s side, and the general marched on Ctesiphon. By the time he got there, the nobles at court had already seized Hurmuz, blinded him (he was killed in prison not much later), and put his son Khosru II on the throne.

This was not quite what Bahram had in mind, and he threatened to kill Khosru II unless the young man relinquished the throne. He had most of the army on his side, so Khosru II fled from the city—into Byzantine territory. Maurice was the only other king strong enough to fight Bahram, and as soon as Khosru got across the border, he sent a letter to Constantinople begging Maurice for help.

Maurice saw the chance to bring the war with Persia to an end. He sent a Byzantine army back to Ctesiphon with Khosru II, and after a protracted battle Bahram was forced out of the city. He fled eastward to the Turks (who first welcomed him and then helped Khosru II by assassinating him), and Khosru II took back his throne.

3

In exchange for the help, Khosru II now agreed to a truce with Maurice and gave him back some of the frontier cities that had been captured decades earlier by the Persians. The two kings sealed the treaty with a marriage: Maurice sent one of his daughters to Ctesiphon to become Khosru II’s wife. As Khosru II was an inveterate collector of women (one Persian writer insists that he had a harem of ten thousand), this was not as meaningful as it might seem; nevertheless, peace descended over the frontier for the first time in almost twenty years.

Finally Maurice could pay some attention to the west. He still had territories in Italy and North Africa, both under the supervision of the military governors known as exarchs; the exarch in Ravenna had a counterpart in Carthage, both men holding command of such soldiers as Maurice had been able to spare, along with the civil authority to make and enforce laws. He also had a trouble spot on the Danube border. The exarchs were not facing any immediate crises, so Maurice decided to deal with the Danube problem first.

4

The Slavs were now crossing over the river in boats to raid the Byzantine lands on the other side. Maurice began to lead his soldiers to the new battlefield, but halfway to the Danube he changed his mind and went back to Constantinople. This did not endear him to the men who were being sent far away from home to fight a fierce enemy. The Slavs had begun to take on a frightening, Hun-like reputation: “refusing to be enslaved or governed,” in Maurice’s own words, “bearing readily heat, cold, rain, nakedness, and scarcity of provisions.”

5

Despite his retreat from the front, Maurice had done his research. He wrote a handbook for his men, the

Strategikon

, describing everything that contemporary generals knew about the Slavs. He warns them to attack in winter, if possible, when the trees are bare, since the Slavs are expert at guerilla tactics and prefer to fight in the deep woods; he tells them to look out for clusters of reeds in the river, since the Slavs might be lying on the bottom, breathing through the hollow stems; he suggests that since the Slavs have multiple chiefs instead of one king, it might be worthwhile trying to bribe some of them to turn against the others.

It isn’t clear how useful these tips were, since the Slavs continued to push across the Danube. These invasions were joined by regular assaults from the Avars, who had come up behind them. Fighting on the northwest border of the empire continued for a full ten years, until the troops were exhausted and battered. Maurice grew more and more unpopular. In 599, the leader of the Avars offered to return twelve thousand Byzantine prisoners of war in return for a generous payment; Maurice refused, and the Avars executed all twelve thousand, which darkened the mood of the army even more.

Then in 602, Maurice—whose treasury must have been all but empty—sent orders to the front: The troops would not be returning home over the winter, as was usual. Rather, to save travel costs and supplies, they would camp across the Danube, foraging in enemy territory for enough food to sustain them.

6

The army refused. Instead, they picked one of their own officers, a man named Phocas, and declared him to be their new general. As his first act, Phocas announced that the army was going home, and began to lead the soldiers towards Constantinople.

Maurice, who had no friends left in the army, rounded up the Blues and Greens, armed them, and told them to defend the city against the approaching troops. Apparently he thought that Phocas intended to take the throne; in fact, the army had sent a letter to Maurice’s son and heir, Theodosius, asking him to take the reins of power away from his father. Theodosius had declined, and it is not clear just how much trouble Maurice was in. But he had created a brand new crisis by arming the Blues and the Greens, who, although reduced in number since Justinian’s day, were still thugs. They stayed on the walls of the city, behaving like a garrison, for a day and a half and then started fighting each other. A mob set fire to the house of one of the senators. Rioting spread throughout the city.

7

That night, Maurice decided to flee. He had gout, which made his journey to the harbor slow and painful. With his wife and sons he finally made it to a ship, and the royal family fled across the strait to the city of Chalcedon. There, Maurice stopped. But he sent his son Theodosius on towards Persia with a letter to Khosru II, asking him to shelter the Byzantine crown prince in return for the favor Maurice had done for him, ten years earlier.

Meanwhile Phocas had arrived at the city, and the army and the Greens had proclaimed him emperor. The Blues, who were the weaker party, retorted that Maurice was still alive, so another emperor could not be crowned. Phocas decided to remedy this problem. He sent a trusted officer across the water to Chalcedon, where the soldier found Maurice and four of his sons and murdered all five of them. Another assassin followed young Theodosius on his path towards Ctesiphon, caught up with him in Nicaea, and killed him.

8

The heads of all six men were brought back to Constantinople and staked out for the people to see, remaining on public view until, as the contemporary

Chronicle of Theophanes

tells us, “they began to stink.” There was a good and practical reason for this: Phocas wanted to make sure that everyone knew Maurice and his heirs were dead. But despite the display, the rumor persisted that Theodosius had made it into Persia and was at the court of Khosru II; the head of the heir to the throne had been too disfigured for easy identification.

9

At first Phocas was popular simply because he was not Maurice. The army was relieved to have a military man in charge; the people of Constantinople hoped for change; and Gregory the Great, in Rome, wrote a fulsome letter welcoming the new emperor to the throne. “Glory to God in the highest,” he began, “who changes times and transfers kingdoms…. We rejoice that the benignity of your piety has arrived at imperial supremacy. Let the heavens rejoice, and let the earth be glad, and let the whole people of the republic, hitherto afflicted exceedingly, grow cheerful.” Maurice had abandoned Rome, and although Phocas had in turn abandoned the Danube frontier (the land was now in the hands of the Slavs), Gregory hoped for better things from the new emperor.

10

But Phocas immediately fell into another war, this one with Persia. Khosru II, who had spent the last few years strengthening his control over his empire, saw his chance to expand. He declared war on Phocas, claiming that Theodosius, the son of Maurice, had indeed survived and was with the Persian army.

Skirmishes began along the border, and the Persian army crossed the frontier in 605; Khosru stationed forces in Armenia, invaded Syria, and stormed through Asia Minor. Meanwhile Phocas, worried about the security of his crown, had been executing possible challengers to the throne left and right. He burned alive the general Narses, who had opposed his reign but who had also been responsible, in the past, for defeating the Persians; Theophanes says that Persian children “shivered when they heard his name” and that “the Romans were greatly distressed at his death, but the Persians joyfully exulted.” He executed all of Maurice’s male relatives, killed the commander of his bodyguard for plotting against him, and then sanctioned the deaths of Maurice’s widow and her three daughters. The Greens turned against him, and he reacted by forbidding anyone with Green affiliations to take part in politics.

11

At that point, North Africa rebelled.

The leader of the rebellion was none other than the exarch of Carthage, an old man and a lifelong civil servant who saw the empire crumbling before his eyes. Thracia and Pannonia were gone, and the Persian army was pressing across Asia Minor almost all the way to Chalcedon. In 610, the exarch assembled a fleet under the command of his son, Heraclius, and sent it towards Constantinople.

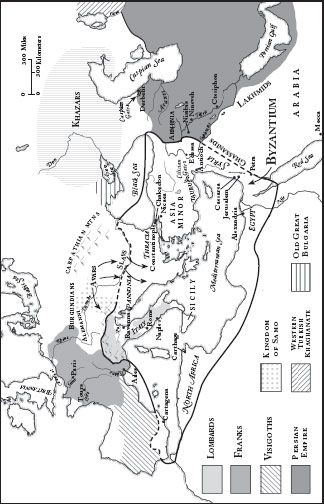

36.1: The Empire Shrinks

When the Byzantine commander at Alexandria in Egypt heard of the expedition, he too joined. The combined force sailed into the harbor at Constantinople on October 4 and found the gates open, the people waiting for them, and Phocas already under citizen’s arrest. As Heraclius entered the city, Phocas was burned alive in the Forum.

12

Heraclius was crowned emperor and found himself at the helm of a mess. “He found,” Theophanes tells us, “that the Roman state had become exhausted. The Avars were devastating Europe, and the Persians had destroyed the Roman army in their battles.” There were few veterans left alive among the troops.

13

The Persians, almost unopposed, conquered Edessa and took the city’s precious relic, the Mandylion, off to some archive in Ctesiphon. The following year, Caesarea fell into Persian hands as well. Simultaneously, the last remnants of the western kingdom crumbled. The Visigothic noble Sisebut seized the crown of the Visigothic kingdom by force in 612 and began to drive the Byzantines out of the lands they held along the coast of Hispania. He captured the imperial cities along the seaboard and, in the words of the Frankish chronicler Fredegar, “razed them to the ground. The slaughter of the Romans by his men caused the pious Sisebut to exclaim, ‘Woe is me, that my reign should witness so great a shedding of human blood!’” His crisis of conscience didn’t stretch to giving the land back, though. He had recaptured the peninsula, and the Visigothic kingdom had reached its height of power.

14

Heraclius decided to sue for peace, even if it came on poor terms. He sent envoys to Khosru II, offering to pay tribute to bring an end to the war. But Khosru II was winning, and he refused. He had already consolidated his power in the northeast of the Arabian peninsula by executing the Lakhmid king and annexing his kingdom; in 614, he marched across to the northwest of Arabia and destroyed the power of the Arab Ghassanids, who had helped protect Syria on behalf of Constantinople.

He then besieged Jerusalem. The city fell. The Persians, who were irate over the length of the siege, stormed in and massacred the population. “Who can relate the horrors that were seen there?” wrote Antiochus Strategos, who pieced together the story from eyewitness accounts. “They destroyed persons of every age, massacred them like animals, cut them in pieces, mowed them down.” Families were herded into the dry moat around the city and put under guard until thirst and heat killed them. In all, nearly sixty-seven thousand men, women, and children died under Persian swords. The most precious relic of Jerusalem, a fragment of the True Cross, joined the Mandylion in the Persian archives.

15