The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (15 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

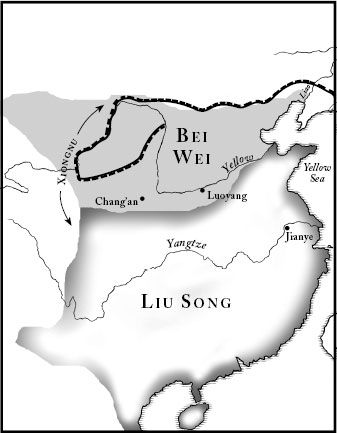

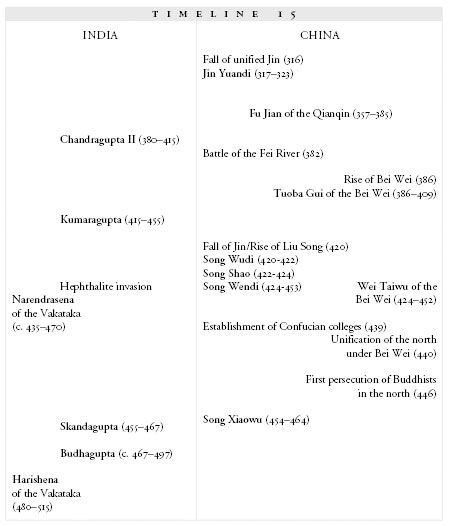

Between 420 and 464, the Liu Song displace the Jin, the Bei Wei of the north brew magic potions, and the first state persecution of Buddhists begins

A

FTER ITS EXILE

to the south, the dynasty of the Jin barely lasted a century. In an attempt to keep a strong core of aristocratic support, the emperors had begun to grant tax relief, exemption from military service, and other advantages to the descendents of the oldest families that had fled from Luoyang. As a result, the noble families of southern China had developed a keen interest in genealogical tables called

jiapu

, which would demonstrate their right to claim these privileges. These tables were becoming more and more complex as the aristocratic families took more and more pride in tracing real physical connections to the past—something that the ex-nomads of the north would never be able to do.

Privilege led to power, and the power of the aristocrats finally brought an end to the Jin. The general Liu Yu, who had helped put down the pirates of the “demon armies” fifteen years earlier, managed to ingratiate himself with the landowning families whose estates had been threatened by piracy and pillage. He gained their loyalty and their support, and in 420 Liu Yu forced the Jin emperor, Jin Gongdi, to abdicate.

Like his predecessors, Liu Yu chose to make the abdication legal, rather than simply getting rid of the emperor; the myth of the Mandate demanded that he gain the throne by virtue, not force. He sent a letter to Jin Gongdi, ordering the emperor to make an edict proclaiming that since Liu Yu had preserved the empire, it was only just that its rule be handed over to him. His army, standing behind him, gave Jin Gongdi a good reason to comply. A ceremony in a building erected specially for this purpose sealed the transfer of power, and Jin Gongdi retired into private life.

1

Now the general became emperor under the name Song Wudi, founder of a new dynasty: the Liu Song.

*

The Jin had ended. Now the two strongest powers in China were the Liu Song of the south and the Bei Wei—still one among several states—to the north.

15.1: The Liu Song and the Bei Wei

Two years after his accession, Song Wudi removed the living memory of the previous dynasty. He ordered one of the court officials to poison Jin Gongdi, now in his late thirties and living peacefully in the capital city. The official, still loyal to the Jin family, wavered in indecision for some time; finally, deciding that the choice lay between killing the man he still thought of as the rightful king of his country and being put to death by Song Wudi for failing his commission, he drank the poison himself.

Song Wudi sent a second official with another dose of poison. When the deposed Jin Gongdi greeted him at the door, he saw at once what was happening. But he refused to be poisoned, something that would have allowed Song Wudi to pretend that Jin Gongdi’s death was natural. Instead, the official smothered him—which allowed Song Wudi to carry on the pretense almost as well. According to tradition, he met with his officials the next day to receive news of the death and wept copiously. Then he gave the murdered king a glorious royal funeral, with hundreds of mourners lamenting around the tomb.

2

Wrapped in the mantle of legitimacy, Song Wudi now reigned as unquestioned emperor of the traditional Chinese realm. But he had been in his late fifties when he took power, and the year after he did away with Jin Gongdi, he took to his bed with his last illness. He passed his throne to his nineteen-year-old son, Shao, a wild teenager who ruled for a little over a year before the throne was taken by Song Wudi’s second son (Shao’s older half-brother), Song Wendi.

Song Wendi became king in 424 and held onto power for twenty-nine years, bringing the new dynasty to a brief high point. Known as the “Reign of Yuanjia,” these twenty-nine years combined successful war (mostly against the nomadic Xiongnu tribes; Song Wendi led a three-year campaign that drove them to the west) and competent administration. In 439, the emperor established four Confucian colleges, each staffed by distinguished Confucian scholars, for the purpose of training the young men of his empire in the principles and precepts of Confucian literature—something that made them better officials and bureaucrats.

3

Soon the Liu Song kingdom in the south had a northern counterpart. In 440, the Bei Wei king, Wei Taiwu, managed to conquer the remaining northern states to unify the north under his rule. The Bei Wei, which had existed as a kingdom since 386, would rule as a northern empire for the next century.

Now the split between north and south was complete.

T

HE

B

EI

W

EI

, like the other northern kingdoms, was made up of people who had not long before been nomadic. Slowly, over the last century, they had begun to settle under a single king, to centralize, to develop laws and regular armies and diplomats. By the time the Bei Wei unified the north, the kingdom had already adopted many of the traditions and ways of the south. The king Wei Taiwu had a Chinese advisor, Cui Hao, who brought Chinese administration and Chinese law into the king’s court and helped him to implement it. In their own eyes, the Bei Wei were mostly Chinese.

4

But Wei Taiwu retained one bit of the nomadic tradition: like a warleader, he kept a harsh and autocratic hand on his people. He organized his kingdom into a strict hierarchy. The countryside was divided into communes, or

dang

, each one with its own administrator. Each

dang

was divided into five villages (

li

), with a leader in each village reporting to the

dang

administrator; each

li

was made up of five

lin

, or neighborhoods; each

lin

consisted of five families.

5

To this tight structure, Wei Taiwu added something that was new in the north: a state religion.

He had been deeply influenced by his Chinese minister Cui Hao, who followed a weird and idiosyncratic version of Taoism. Classic Taoism taught nonaction, withdrawal from the world of strife and politics in order to focus on personal enlightenment. The mythical Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove, a group of Taoist philosophers who were said to have lived in the previous century, were the model for perfect Taoist detachment: they “revered and exalted the void, and nonaction…drank wine to excess, and disregarded the affairs of this world, which seemed to them like duckweed.”

6

Originally, Taoism had not paid much attention to the afterlife; promises of immortality were not part of its philosophy. But some decades earlier, a Chinese philosopher named Ge Hong had begun to teach a new kind of Taoism. This Taoism encouraged its followers to seek enlightenment through magical elixirs that would lift the drinker to a higher spiritual level and—as a side effect—bring eternal youth. Ge Hong claimed that his family had received three texts from a divine being, the “Scriptures of the Elixirs” (or “Taiqing texts”), with instructions on how to create these magical potions. What earlier Taoists had achieved through philosophy, fifth-century Taoists could achieve with chemical aids; Ge Hong, the Timothy Leary of Chinese Taoism, had turned Taoism into something more like a cult than a philosophy.

7

In 415, one of the chief teachers of this new kind of Taoism, Kou Qianzhi, left the mountain where he had been living as a hermit and came into the Bei Wei, ending up at Wei Taiwu’s court. Wei Taiwu, already enamored with this new Taoism, welcomed him and built him a temple, putting him (and his disciples) up at taxpayers’ expense. In 442, Kou Qianzhi gave the emperor a book of charms: “After this,” the historian C. P. Fitzgerald writes, “every Emperor of the Wei dynasty used to proceed to the Taoist temple at his accession and obtain a charm book.”

8

Taoism had become something completely new: a state religion that lent its magical powers to support the emperors and their claim to power.

Wei Taiwu’s enthusiasm for his new religion led him to defend it with the sword. In 446, Wei Taiwu was forced to put down a rebellion led by a guerilla fighter who had stored weapons in Buddhist temples. Wei Taiwu was convinced that Buddhist priests had been part of the conspiracy to overthrow his magically confirmed reign. He began by outlawing the religion: “I am determined to destroy every trace of Buddhism from my kingdom,” he announced, in an official edict declaring Buddhism anathema. “I have been appointed by Heaven to establish the right and to sweep away what is false.”

9

He then ordered his men to slaughter all of the Buddhist monks in the empire, starting in the capital Chang’an. The killings began; they were only mitigated, in part, by Wei Taiwu’s son, the crown prince Huang. Huang was himself a Buddhist, and when he discovered that his father was about to issue the edict, he sent secret messages to all of the Buddhist priests he could reach, warning them to flee. Many of them did. But not all; many more were captured and put to death, and the Buddhist temples across the entire Bei Wei empire were reduced to rubble.

O

NCE HE HAD PUT DOWN

the rebellion and killed the (alleged) conspirators, Wei Taiwu suggested to Song Wendi of the Liu Song that the two Chinese empires make a permanent peace, sealed with a marriage alliance. In his own eyes, his empire was just as Chinese as the south. Song Wendi not only disagreed but was so insulted by the barbarian attempt to behave like an equal that he invaded the Bei Wei territory twice.

10

The invasions damaged his own army and accomplished nothing. And despite its indignation over the barbarian presumption and its own claims to be a legitimate royal family, the Song was weakening while the Bei Wei prospered. Song Wendi’s younger son Song Xiaowu became emperor in 454 and ruled for ten years; contemporary chroniclers pointed to his reign as a time when the Mandate began to fade. Song Xiaowu was frivolous and pleasure-centered. He preferred hunting to state business, and instead of addressing his officials and nobles of the court by their proper titles (something in which they placed great stock), he gave them undignified nicknames.

So shallow and worthless was he that when he died, ten years after his accession, his son and heir showed no grief upon hearing the news. His lack of proper sentiment shocked his ministers: “The dynasty will not be long before it perishes,” they cried.

11

The natural affection between father and son had been warped; the natural order of things was twisted and distorted; the kingdom would soon follow the same path.

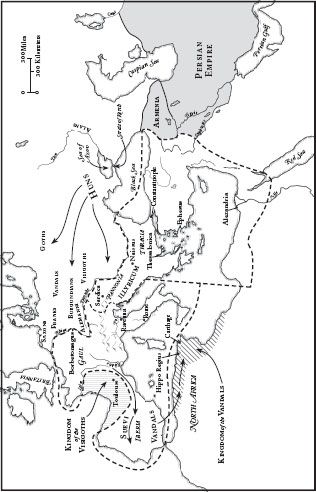

Between 423 and 450, the Vandals build a pirate kingdom in North Africa, and the bishop of Rome becomes the pope while Aetius takes control of the western empire and the Huns approach its borders

W

HILE THE EASTERN

R

OMAN EMPIRE

hosted theological councils, the western empire struggled for survival. Britannia had been abandoned; under Wallia and his successor, the Visigoths prospered in southwestern Gaul, allies of Rome but a sovereign state in their own right; and despite the efforts of a combined Roman and Visigothic army, the Vandals had managed to take over much of Hispania, forming their own kingdom there and shaking off all Roman attempts to retake the former province.

The western emperor Honorius died in 423. After a scuffle for power that occupied the best part of a year, his nephew Valentinian III (six years old, son of Honorius’s sister Placida and her second husband, the general Constantius) was crowned as emperor. Placida, the little boy’s regent, was soon forced to appoint as

magister militum

the Roman soldier Aetius, the hostage who had been sent first to the Visigoths and then to the Huns.

Aetius had been returned by the Huns some time earlier, although we have no record of exactly when. But in his years with the Huns, he had developed a friendship with his hosts. After Honorius’s death, Aetius—twenty-five years old, hardened by exile, and accustomed to tricky situations—made it clear to Placida that his Hun friends would descend on Ravenna unless he was given the highest military post in the west. Placida gave him both the title and the authority that went with it.

Meanwhile, another part of the western empire disappeared.

In 429, the king of the Vandals in Hispania, Geiseric, built a fleet of ships and sailed across the mouth of the Mediterranean Sea. He then began to march along the North African coast, conquering his way through Roman provinces and independent African kingdoms alike. By 430, he had reached the Roman city of Hippo Regius. His army laid siege to it while the elderly bishop Augustine lay inside, suffering from his final illness. The siege dragged on for eighteen months; the man who had written of the ultimate triumph of the kingdom of God died with Vandals still surrounding his city and no hope of relief.

When Hippo fell, Geiseric marched on to Carthage. It was defeated and overrun in 431; Geiseric lined up the Roman soldiers who had defended it, forced them to swear an oath that they would never again fight against a Vandal army, and then let them go. North Africa was lost to Rome.

Before long Geiseric decided to concentrate his energies on his North African holdings. He abandoned Hispania and ruled as a North African pirate-king, his headquarters at Carthage, master of a powerful Vandal kingdom that had sprung up as quickly as a mushroom. Aetius,

magister militum

and now the most powerful man in the western empire, made no effort to fight for the Roman territories across the Mediterranean. He sent the nominal emperor Valentinian III off to visit Constantinople, where Valentinian (now nineteen) married his co-emperor’s daughter, creating a blood alliance between the two halves of the empire. While the emperor was away, Aetius went to war in Gaul.

North Africa was lost, the Visigoths were firmly established in southwestern Gaul, and Hispania was too far to recapture; parts of it now fell into the hands of another Germanic tribe, the Suevi, and the Visigoths began to push their way into the land vacated by the Vandals. But Aetius had no intention of losing the land on his northwestern frontier as well. He had already put down a rebellion of the Germanic Franks who lived within the Roman borders as

foederati

; now he mustered his army and marched against the Burgundians, yet another Germanic tribe who had settled in the Rhine valley as

foederati

. Their king, Gundahar, had established his capital at Borbetomagus (later the city of Worms) and was showing worrying tendencies towards independence.

Aetius hired Hun mercenaries to fight with him against the Germanic upstarts. In a brutal battle in 437, the Romans and Huns together destroyed Borbetomagus, crushed the Burgundians, and killed Gundahar. The slaughter survived in the tales of the Germanic tribes, and came down into the

Nibelungenlied

, the Song of the Nibelungs; the Burgundian king Gundahar, whose name is rendered Gunther, welcomes the dragon-slayer Siegfried to his court at the epic’s beginning, and at the end travels to the land of the Huns and is murdered by treachery.

Aetius had now used the Huns for years to establish his own power. But the Huns were not tame mercenaries, and Aetius was about to find himself the loser in his dangerous game.

16.1: The Approach of the Huns

Up until this point, the Huns had not launched any sort of sustained assault on the Romans. Stories of their unearthly ferocity and strength had become a staple of Roman history: “They made their foes flee in horror,” says Jordanes, “because…they had, if I may call it so, a sort of shapeless lump, not a head, with pin-holes rather than eyes.”

1

But the Huns were not yet a great threat to the empire; Hun raids, when they troubled the borders, were damaging and scary, but the Huns always withdrew.

The Huns had not been able to sustain an attack because they had never been a single unified force. Like the Germanic barbarians, they were a coalition of tribes with no particular loyalty to each other. “They are not subject to the authority of any king,” Ammianus Marcellinus writes, “but break through any obstacle in their path under the improvised command of their chief men.” They did not plant or tend crops; instead, they drove cows, goats, and sheep in herds across the countryside, which meant that it took a lot of pasture to feed a group of Huns. So they had remained in small nomadic knots, easier to support, economically more stable than a massive monolithic force. They had no strategy for taking over the world. They were simply trying to survive.

2

But even while Aetius was hiring those independent bands of Huns to fight for him, Hun society was changing. Over the preceding decades, they had made their way from the bare foraging ground east of the Black Sea, into the relatively rich and cultivated land of the Goths, land that allowed at least the possibility of feeding themselves in a new way and coalescing into a much larger group. Sometime around 432, the warrior chief Rua—uncle of the young hostage Attila, who had been returned to his own tribe after spending some years at Ravenna—had managed to extend his power over Hun tribes unrelated to his own. By 434, Attila and his brother Bleda had succeeded their uncle as joint chiefs over an expanding Hun coalition. Six years later, Attila and Bleda led their combined Hun army in an attack on a Roman fort on the Danube. They continued to rampage up and down the Roman side of the river, flattening forts and towns, before they withdrew in 441 and agreed to negotiate a truce.

3

For two years, the Huns kept the truce. Then, in 443, they headed for Constantinople with battering rams and siege towers. Theodosius II, evaluating the approaching force and deciding that it would be prudent to settle rather than fight, paid them off and agreed to a crippling yearly tribute. Once again the Huns retreated, and another temporary silence descended over them.

Not long after the retreat from Constantinople, Attila killed his brother Bleda and proclaimed himself the single, unopposed king of his people. In the breathing space provided by their truces with the eastern and western empires, the Huns were mutating from a loose coalition into a ruthless conquering horde. The Huns, wrote the exiled bishop Nestorius in his lengthy defense of his own beliefs (a book that touches only briefly on outside events), had been “divided into peoples” and were only robbers who “used not to do much wrong except through rapacity and speed.” But now they were a kingdom: “very strong, so that they surpassed in their greatness all the forces of the Romans.”

4

W

ITH THE

H

UNS

on their very doorstep, the emperors of eastern and western Rome occupied themselves with a quarrel over theological power. In 444, the new bishop of Rome, Leo I, wrote an official letter to the bishop of Thessalonica, informing him in no uncertain terms that the bishop of Rome, as the heir of Peter, was the only churchman with the authority to make final decisions for the entire Christian church. The bishop of Thessalonica had, in Leo’s view, overstepped himself by bringing another bishop up before the civil court in his province. No matter what the reason for this arraignment, Leo scolded, only Rome had the right to exert authority over other bishops:

Even if he had committed some grave and intolerable misdemeanour, you should have waited for our opinion: so as to arrive at no decision by yourself until you knew our pleasure…. Though all priests have a common dignity, yet they have not uniform rank; inasmuch as even among the blessed Apostles, notwithstanding the similarity of their honourable estate, there was a certain distinction of power, and while the election of them all was equal, yet it was given to one to take the lead of the rest. From which model has arisen a distinction between bishops also…the care of the universal Church should converge towards Peter’s one seat, and nothing anywhere should be separated from its Head.

5

Leo did not depend only on this letter to establish his authority. He appealed to the throne, and in 445, Valentinian III (still dominated politically by his

magister militum

Aetius) agreed to make a formal official decree that recognized the bishop of Rome as the official head of the entire Christian church. Leo the Great, the bishop of Rome, had become the first pope.

His claim to imperially sanctioned power infuriated the bishop of Alexandria. The bishops of Rome and Alexandria had been allies at the 431 council in Ephesus, but since then, the power of Alexandria had grown. Now the bishop of Rome saw the current bishop of Alexandria, Dioscorus, as his primary competition both for theological power and for the ear of the emperor.

Dioscorus was just as suspicious of Leo the Great, and he tried to flex some theological muscle in return. Although both men were monophysites (“one-nature” supporters),

*

Dioscorus’s version of monophysitism was more extreme than Leo’s; he insisted that “the two natures of Christ became a single divine nature at the incarnation,” an interpretation that almost veered back over into heresy again, since it tended to remove Christ’s humanity from view.

6

In 449, Dioscorus called a hasty church council in Ephesus and talked the bishops who were able to arrive on short notice into signing documents that affirmed

his

version of monophysitism as orthodox. According to later accounts, some of the bishops signed blank papers (the theological content was filled in later), while others who didn’t sign simply found that their names mysteriously had appeared at the bottom of pro-monophysite statements. All of this earned the council the title “Robber Council,” or the Latrocinium—a term condemning the council as illegitimate.

†

Dioscorus then wrapped up this performance by declaring the bishop of Constantinople a heretic and by excommunicating the absent bishop of Rome, a clear attempt to usurp the authority of Rome by transferring it to Alexandria. Leo I responded by excommunicating everyone who had been at the council.

Since they had all now excommunicated each other, the struggle for theological power appeared, temporarily, to be at an impasse. And at that moment, while the bishops were declaring each other to be anathema, two of Attila’s lieutenants appeared in Constantinople, carrying a threat from their king.

The lieutenants were a mixed pair: one was a Hun, the other a Roman-born man of Germanic blood named Orestes. Their threat was couched in diplomatic terms. Attila accused the eastern empire of breaking the terms of its truce with him, and demanded that ambassadors (“of the highest rank”) be sent to meet him at Sardica to resolve the issue.

7

Theodosius II and his advisors, meeting hastily together, organized a small party of ambassadors to travel back to Attila’s headquarters. One member of the party, the historian Priscus, later wrote of the Roman journey into Hun-occupied territory. Passing the sacked city of Naissus, where Constantine the Great was born, they saw that it had been reduced to heaps of stones and rubble. So many bones of the dead city’s defenders littered the ground that the party was unable to find a clear space to camp for the night.

8

On the journey, the eastern Roman embassy found its paths intersecting with an embassy from Ravenna, also hoping to negotiate a peace with Attila. Together the representatives of both halves of the empire finally arrived at Attila’s headquarters, on the other side of the Danube, a village he had built to be his temporary capital. Priscus was stunned by the workmanship: it was, he says, more “like a great city” than a village, built of “wooden walls made of smooth-shining boards…dining halls of large extent and porticoes planned with great beauty, while the courtyard was bounded by so vast a circuit that its very size showed it was the royal palace.”

9