What If Ireland Defaults? (15 page)

Read What If Ireland Defaults? Online

Authors: Brian Lucey

In the Irish case, no debt write-downs of senior bondholders were considered or allowed, while large amounts of emergency liquidity assistance were given by the ECB to Irish banks via the Central Bank of Ireland to allow private banks to continue their operations.

The risk of the creation of emergency liquidity assistance for a private bank is borne by the national central bank that decides to fund the private bank in that manner. The emergency liquidity assistance being given is equivalent to the promissory notes being written for the damaged Irish banks, discussed above, in that the national government, itself in rough shape economically, must have the appearance of guaranteeing large amounts of capital. The implicit lender of last resort â the ECB â waits to learn whether it will be required, or not. In the event of an Irish default, it certainly would be.

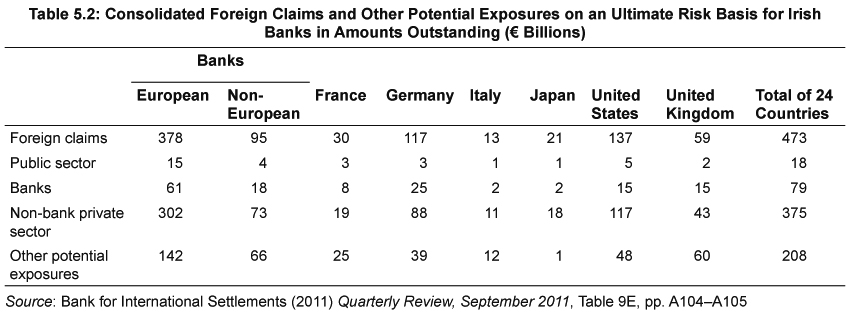

Finally, to get a clear(ish) picture of who might be affected by any default, we have to ask who our creditors are. The Bank for International Settlements

7

publishes annualised data on debt holdings by banks and by country. These statistics are skewed in the case of Ireland by the presence of large banking conglomerates â hence the use of the â(ish)' above â but Table 5.2 gives the debt position as of March 2011 for Ireland's banks.

We can see from Table 5.2 that Ireland's public sector has just over â¬18 billion held in European and non-European banks, with foreign claims amounting to close to â¬473 billion outstanding at the end of March 2011. The non-bank private sector in Ireland has â¬302 billion in European banks and â¬73 billion in non-European banks. The liabilities of the banking system in Ireland are roughly four times the yearly income of the nation. The liabilities of the banking system matter in the consideration of any Irish default. The reason for this is simple: Ireland's banks are guaranteed by the sovereign, and are inextricably bound to the state via the banking guarantee and by the provision of emergency liquidity assistance. Any change in the terms of debt settlement agreements between a sovereign and its creditors will perforce damage the banking sector.

What default strategies might the Irish economy employ? Let us work under the assumption that Ireland remains within the Euro currency and therefore is not permitted to require senior bondholders to âburden share' in the losses of the banks they invested in.

It is important to note that the rest of the debt either accrued to this point or locked in via the EU/IMF loan arrangement is either sovereign debt or a mixture of local and savings debt and the promissory notes written to cover the losses some private banks sustained following the collapse of the construction sector.

Remembering that a sovereign default is simply not paying interest or a principal owed to creditors, there are several default strategies a government might employ.

The first default strategy is the ânuclear' option of reneging on most of the outstanding debt of the nation. There are very few examples of this type of default outside of wartime episodes, where the debtor nation feels it need not pay back the debts accrued to an aggressor. The post-war category includes civil wars, and examples of these defaults would be China in 1949, Czechoslovakia in 1952 and Cuba in 1960. In these cases, the debt reneged upon is characterised as âodious'.

The second type of default is partial, and occurs following a credit bubble. These are by far the most common, and Russia's default in the 1998 (discussed in Chapter 7 of this book) is the largest recent example.

The third type of default is a âsoft' default, or a restructuring of privately held debt over time. So the debtor agrees to repay the full amount but over a longer time horizon with perhaps a lower interest rate. This is a default in that the interest applied to the restructured loan will typically not yield the same return as the original debt contract. Examples of post-war debt restructuring abound, especially in the 1970s and early 1980s, and include Turkey in 1978, Romania in 1981 and Poland in 1981. Almost every Latin American economy defaulted or restructured their debts in this period as well.

Ireland really has two choices: it can default on its sovereign debt or try to recoup some of the losses on promissory notes. The first option should be resisted until all other options have been exhausted. The second option carries no fiscal or monetary consequence beyond a renegotiation with the ECB over the terms of the repayment of the promissory notes. This is a default, as defined here. But it is also not a default. No credit default swaps will be triggered; no credit ratings will be damaged. The Irish state is agreeing, through a third party, to pay itself less and over a longer time. This would be a very Irish default.

Now, what would the consequences for such a default be in Europe? We must always consider the political economy of each situation Ireland finds herself in. Assuming Ireland remains steadfast in its application of austerity policies, and assuming the stability of the Eurozone was at stake, a renegotiation of Ireland's emergency liquidity assistance, or the promissory note structure, would give precedent to other nations to act in a similar manner.

For the ECB, the creation of assets by national central banks with banking systems in trouble is anathema. Yet the dilution of the promissory note structure would, in all likelihood, have no significant effects on the balance sheet of the ECB, beyond the creation of an expectation that the ECB would move to shore up the balance sheets of its wayward national central banks via emergency liquidity assistance measures.

In summary, then, at the end of 2011 Ireland has few options to default, when considering the political economy of a nation inured to austerity policies, bent under EU and IMF conditionality, and zealous to remain in the Eurozone. The benefits of a default are not paying back all of one's debts. The costs come when new debt must be raised, and when trade depends upon certainty. Markets are forward looking, but they do remember sovereign defaults â for a while, at least. The Eurozone will not tremble at the restructuring of our debts, owed only to ourselves.

Endnotes

1

In this chapter I use gross national income (GNI) rather than gross domestic product (GDP) or gross national product (GNP). Gross national income is similar to gross national product but also deducts indirect business taxes and EU taxes and subsidies. The difference between gross national and gross domestic product is that while GDP includes the income of the multinational sector, GNP does not.

2

Karl Whelan (2010) âPolicy Lessons from Ireland's Latest Depression',

Economic and Social Review

, Vol. 41, No. 2, pp. 225â254.

3

Colm McCarthy (2010) âFiscal Consolidation in Ireland: Lessons from the Last Time' in Stephen Kinsella and Anthon Leddin

Understanding Ireland's Economic Crisis: Prospects for Recovery

, Dublin: Blackhall Publishing, pp. 103â116, and Stephen Kinsella (in press) âIs Ireland really the Role Model for Austerity?',

Cambridge Journal of Economics

.

4

Stephen Kinsella and Anthony Leddin (2010)

Understanding Ireland's Economic Crisis: Prospects for Recovery

, Dublin: Blackhall Publishing, for an overview of how the crisis came about in the early 2000s.

5

Constantin Gurdgiev, Brian M. Lucey, Ciaran Mac an Bhaird and Lorcan Roche-Kelly (2011) âThe Irish Economy: Three Strikes and You're Out?', working paper available from SSRN:

6

Hyman P. Minsky (1986)

Stabilizing an Unstable Economy

, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

7

Bank for International Settlements (2011)

BIS Quarterly Report, Q4 2011

, available from:

How to Survive on the

Titanic

: Ireland's Relationship with Europe

Megan is Head of European Economics at Roubini Global Economics and previously worked as a senior economist with the Economist Intelligence Unit.

The prospects for the Eurozone do not look good. A number of weaker Eurozone countries â Greece, Ireland and Portugal â are being kept on life support by bailout packages with terms and conditionality that may well end up killing the patients. Italy and Spain are increasingly looking insolvent and will probably be forced to seek bailouts as well. Without growth in the region, a negative feedback loop of austerity and recession has already begun. In order to regain competitiveness and return to growth, a number of Eurozone countries are likely to opt to abandon the common currency. However, against this very grim backdrop Ireland has been held up by EU leaders as a bright light. The small, open economy has been a model student in terms of complying with the terms of its bailout agreement and hitting all of its targets. The EU, European Central Bank (ECB) and International Monetary Fund (IMF) (the so-called troika) see Ireland's performance as a vindication of their response to the crisis, with competitiveness gains and economic growth reported in the first half of 2011.

But any good news in Ireland must be set against the enormous costs the country has had to bear. It experienced a depression in 2008â2010, the state has been saddled with the private debt of the banking sector, the public has seen five austerity budgets and counting, and unemployment has remained stubbornly high. For these reasons, since the beginning of the Eurozone crisis in 2008 the public, and more recently members of the Irish political elite, have increasingly questioned whether the benefits of Eurozone membership still outweigh the costs. This question will only increase in relevance if, as is likely, other countries drop out of the common currency in an effort to regain competitiveness. Ireland's calculus in determining whether to stay in the Eurozone or exit is unique because of its reliance for economic growth on the output of multinational corporations (MNCs), many of which use Ireland as a springboard into the single market. To leave the Eurozone would be to risk deterring these MNCs by undermining Ireland's position within Europe. It is in Ireland's best interest to remain in the Eurozone in order to protect the country's relationship with the EU and, therefore, its growth model.

Prospects for the Eurozone Are Grim

Before considering the prospects for Ireland's relationship with Europe, it is necessary first to canvass the likely future of the Eurozone and EU. By the end of 2011, the region's crisis had shown no signs of stabilising and had spread beyond weaker Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece and Spain (the PIIGS) and well into the core. Not only were Italian and Spanish bond yields shooting up to clearly unsustainable levels, but Belgian, Austrian and French bond yields had risen sharply as well. Meanwhile the prospect of weaker countries leaving the Eurozone was becoming increasingly likely.

Response a Bust

The crisis response by EU leaders so far has been lacklustre at best. The main component of the response for weaker countries facing unsustainable borrowing costs in the markets has been a bailout package from the EU and IMF accompanied by strict conditionality. The conditionality is meant to ensure measures are implemented to achieve two things: to boost the countries' competitiveness and to rein in their fiscal dynamics. However, if we use these two objectives as our metrics for success, this plan has been a clear bust everywhere in the periphery except arguably in Ireland. Using unit labour costs as an indication of competitiveness, Greece and Portugal have seen their unit labour costs fall only very mildly, while Ireland has had its unit labour costs fall more sharply. Using budget deficits as an indicator of fiscal developments, Greece's primary deficit (the government deficit excluding debt servicing costs) actually increased in 2011 compared with 2010. Portugal reduced its 2011 budget deficit by implementing a number of one-off measures but this will not work in the future, particularly as Portugal's gross domestic product contracts. According to the troika's quarterly assessment, Ireland was ahead of the budget deficit reduction targets in 2011 as stipulated by the bailout programme.

In the case of Greece, EU leaders went beyond providing a bailout programme with strict conditionality, allowing Greece to negotiate a voluntary debt exchange with its creditors, dubbed private sector involvement (PSI). According to the terms of this exchange, banks holding Greek government debt would agree to accept longer-dated bonds, effectively writing down their holdings by at least half. But the effectiveness of this strategy is questionable. While PSI helps to address a country's debt stock problem, it does not address the flows of debt that a country like Greece will continue to accrue in the absence of structural reforms and economic growth.

Greece as a Model

EU leaders have gone out of their way to insist that Greece is a unique case. However, it seems much more likely that Greece will become a model for how to handle weaker countries in the Eurozone. At the time of writing (early 2012), Greece faces a stark choice in terms of how to return to growth. The country can either continue along its current path, implementing harsh austerity measures and savagely cutting wages and prices in an attempt to undergo an internal devaluation and regain competitiveness. This would involve tolerating up to a decade of recession or depression. Alternatively, Greece could abandon the Euro, reissue the drachma and see it devalue massively. The result would be a much faster boost in competitiveness and return to growth.

Leaving the Eurozone would certainly be painful and messy for Greece. However, some of the deterrents against leaving, such as the prospect of sovereign and bank default, seem increasingly likely even within the Eurozone, which impacts the costâbenefit analysis of Eurozone membership. Furthermore, it would be in everyone's best interests â the core countries, the peripheral countries, the ECB, the IMF and Greece â for a Greek Eurozone exit to be as managed and negotiated as possible. It therefore seems likely that it will be handled much like a divorce. Greece and the EU would decide that they simply do not belong together, and the EU would offer bridge financing and take efforts to protect its own banking system as it facilitates Greece's exit from the common currency.

Any managed exit by Greece wouldn't take place in a vacuum. Once Greece exits, Portugal would likely face the same choice about competitiveness and growth. It too would choose to exit the Eurozone. Ireland would face the same decision, and while it may choose to follow suit it would be misguided to do so. This rippling wave of potential exits from the Eurozone would not stop with the three countries currently in receipt of bailout funding. Ongoing efforts to provide a backstop for the huge financing needs of Italy and Spain look insufficient to do anything more than buy some time. Eventually, these two countries will also face the same question as Greece: they can either return to growth via a decade of austerity and recession/depression or they can choose to leave the Eurozone in as managed a fashion as possible.

Changing the Rules of the Game

A break-up of the Eurozone as outlined above is very likely, but it is not inevitable. If a number of conditions are met, the common currency can stick together. First and foremost, the Eurozone must return to growth. For this to happen, the ECB must provide massive amounts of quantitative and credit easing. Second, the ECB must talk down the Euro aggressively so that it is at parity with the US dollar. However, given that the Eurozone is one of China and the US's biggest export markets, it is questionable whether China or the US would tolerate such a weak Euro. Third, core countries would need to provide fiscal stimulus measures to trickle into the periphery. The chances of all three of these measures occurring simultaneously are extremely low.

Beyond these measures to stimulate growth in the Eurozone, EU leaders would need to fundamentally change the structure of the Eurozone so that it includes either fiscal transfers or joint assets and liabilities (in the form of Eurobonds). In late 2011, EU leaders (except for UK Prime Minister David Cameron) agreed in theory to treaty changes (dubbed the âfiscal compact') that were touted as the first step towards fiscal union. At the heart of these changes is more fiscal discipline, with more automatic sanctions imposed on countries that miss fiscal targets. These are not steps towards fiscal union. Rather, the treaty changes proposed institutionalise the asymmetric adjustment occurring in the Eurozone, whereby the peripheral countries are forced to make all of the adjustment while the core countries do not adjust at all. Not only is this a surefire recipe for recession in the peripheral countries, but it also indicates how far EU leaders are from accepting fiscal transfers or Eurobonds.

Eurozone Break-Up the Death Knell for the EU?

According to the Treaty on European Union, a country cannot exit the Eurozone without also exiting the EU. But this is a legal technicality, not a practical, moral or ideological necessity. Legal impediments can easily be overcome by agreeing and writing new rules. The EU existed without a common currency before the introduction of the Euro. Those countries that are currently in the EU but do not use the Euro benefit significantly from the single market. It is in all EU member states' best interests to keep the common market together, and consequently it seems likely new legislation to allow for this will be agreed.

Ireland's EU Relationship: It's Complicated

The Irish public has been increasingly ambivalent about EU membership for more than a decade. Previously, sentiment towards the EU was overwhelmingly positive, reflecting a wide range of benefits that were associated with membership. There were direct economic gains, both in terms of structural funds received from the EU as well as, crucially, the massive expansion of the market into which companies based in Ireland could sell. More generally, EU membership contributed to a national feel-good factor. It was seen as a way of emerging from the UK's shadow to act on an equal footing with Europe's major powers in the numerous EU policy areas requiring unanimous decisions.

However, Ireland is deeply protective of its sovereignty and anti-European sentiment emerged and hardened in response to EU treaty revisions that were perceived by many to encroach too far on Ireland's right to make decisions for itself. This was highlighted in 2001 and 2008 when Ireland rejected the Nice and Lisbon treaties, respectively. Both treaties were subsequently approved at the second time of asking, but for critics of the EU these second votes were simply further evidence that Brussels was contemptuous of democracy at the national level.

Anger directed at the EU has intensified and widened since the eruption of the Eurozone crisis, largely in response to key terms of Ireland's EU/IMF bailout, such as the ECB's insistence that senior bondholders in Ireland's zombie banks be made whole (repaid in full) by the taxpayer. There is now a clear dichotomy in Irish society and politics between those who argue that Ireland's national interest lies in unilaterally breaking with the terms of the bailout, and those who argue that Ireland's core interests lie in being anchored within European political and economic structures, even if the price is compliance with bailout rules that are perceived to be unjust.

The European question is an increasingly important driver of the country's domestic politics. While the current coalition government of Fine Gael and Labour has not rocked the boat with Europe since taking office, on the campaign trail both parties sought to woo voters by adopting a more confrontational stance than usual. Moreover, the government's relative meekness in office (the Minister for Finance, Michael Noonan, has repeatedly called for debt relief from the troika only to back down immediately when rebuffed) has seen it lose support to the populist left-wing nationalism of Sinn Féin, previously a fringe party with its roots in the Northern Ireland conflict, but now the second most popular party in Ireland according to one opinion poll in late 2011.

In order to lessen the attraction of Sinn Féin's message of easy unilateralism, the government has sought to up the stakes by highlighting the risk that Ireland might end up outside the Eurozone. After EU leaders agreed in principle the terms of their âfiscal compact' in late 2011, Minister Noonan announced that any Irish referendum on the changes would amount to a vote on whether the country would remain in the Eurozone.

Ireland's Growth Model Tied to the EU

If even the finance minister is openly acknowledging the possibility of Ireland leaving the Eurozone, is that the best course of action for the country? The answer is no for two main reasons: an Irish exit is more likely than others to be disorderly and the risk to Ireland's growth model from exiting is likely to be even greater than for other countries.

The longer Ireland continues to comply with its bailout agreement, the greater its debt burden becomes. If the Eurozone is going to fall apart anyhow, some would argue the Irish government should stop saddling itself with ever higher debts from making bondholders of zombie banks whole or repaying the promissory notes that were used to pour cash into those banks as the crisis was unfolding. This argument holds even more weight if Greece and Portugal default on their sovereign debt and choose to exit the Eurozone. If other countries are not repaying their bondholders, why should Ireland?

The answer to this depends in part on how the exit process is handled. I have argued that Greece and Portugal will agree with the troika that they are not meant to be in the common currency, and their exit will be managed and orderly. However, it is doubtful that the troika will agree Ireland should follow suit and leave the Eurozone. Ireland stands apart from the other bailout countries in that it has not only hit all of its bailout targets, but it shown some signs of a return to growth as well (albeit followed by further contraction). The EU has gone out of its way to praise Ireland for being a model student, complying with all the bailout rules and vindicating the troika in its insistence that austerity is the best path towards competitiveness and growth. It is unlikely the troika will turn around and accept that its plan for handling the crisis is misguided and that Ireland could potentially be insolvent.