What If Ireland Defaults? (11 page)

Read What If Ireland Defaults? Online

Authors: Brian Lucey

The striking feature of Figure 3.2 is that over the twelve years' horizon, only six countries of the Eurozone have managed to post a cumulative external surplus, while only one country (Finland) has managed to live within its means both in terms of external balance and fiscal balance.

Another striking feature of the graph is that France was running dual external and fiscal deficits. Germany â another paragon of âstability' â ran structural deficits on the fiscal side, i.e. spent beyond its means when it comes to government expenditure outside what is needed to correct for recessionary imbalances. Ditto for the Netherlands.

For Ireland, âexports-led growth' is, alas, historically not an engine of external balances. The cumulated current account deficit for the country is -19.5 per cent of GDP. Reversing twelve years of that experience will require re-wiring our economy, preferences, political and institutional structures, etc. â all long-term and exceptionally hard to achieve measures.

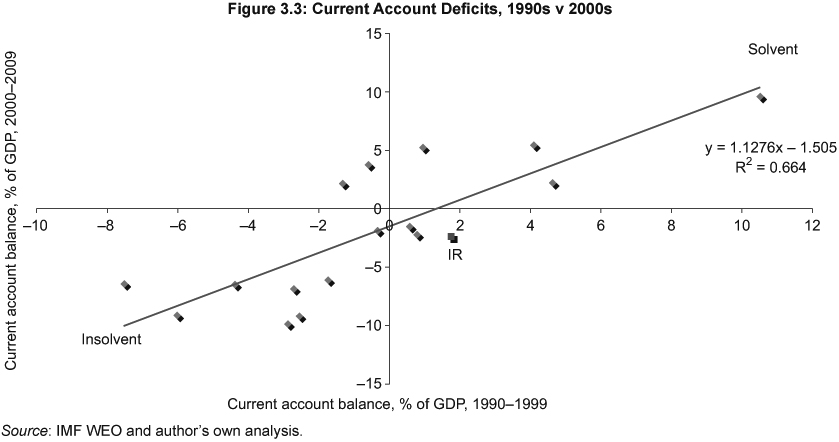

The fact is, deficits are sticky and thus very hard to reverse. Past deficit experience shapes much of the future performance, as illustrated in Figure 3.3.

Once you are insolvent for a decade (1990s) you are highly likely to remain insolvent for the next decade as well (2000s). And the headwinds against Ireland reversing that and moving into strong surpluses in its current account in years ahead are strong. If we look at the transition from the 1990s external balance position to the 2000s position, the following holds for the Eurozone:

- Finland and the Netherlands stand out as the only two countries that managed to improve their surpluses on the current account side between the 1990s and 2000s averages.

- France, Belgium and Luxembourg are the only three countries that managed to retain surpluses, but their performance weakened between 1990s and 2000s.

- Malta was the only country that managed to reduce its external deficits between the 1990s and 2000s in terms of averages.

- Portugal, Greece, Estonia, Cyprus, the Slovak Republic, Spain, Ireland, Slovenia and Italy all saw average deficits of the 1990s deepening in the 2000s.

- Only two economies, Austria and Germany, managed to reverse previous deficits (in the 1990s) to surpluses in the 2000s.

That means that, historically, the chance of reversing an average current account deficit in the previous decade to a surplus in the next decade is 2 to 17 or less than 12 per cent. Not an impossible feat, but an unlikely one.

Current account deficits do appear to correlate closely to general government deficits and structural fiscal deficits. Thus insolvency of the deepest (across all three measures) variety was the domain of ten out of seventeen member states when it comes to the last twelve years of Eurozone history. Another five member states are insolvent by two out of three criteria. Lastly, only two member states â Finland and Luxembourg â have actually been fully solvent since 2000.

And, of course, Ireland stands out once again, with:

- Relatively solvent external balances averaging 1.74 per cent of GDP in 1990â1999 (fourth strongest) yielding to an average annual current account deficit of 2.35 per cent over 2000â2009 period (seventh worst performer in the Eurozone)

- Mildly insolvent public finances in 1990â1999 (with average general government deficits of 0.90 per cent of GDP; third best performance in the Eurozone) yielding to a 1.02 per cent average deficit in 2000â2009 (twelfth best performance in the Eurozone)

- Substantial structural deficits in the 1990â1999 period (with an average structural deficit of 3.09 per cent; the eleventh highest in the Eurozone) yielding to a 6.14 per cent average deficit in the 2000â2009 period (second highest after Greece)

It is worth noting that in the 1990s Irish current account surpluses were subject to potentially higher tax revenue capture than they are today. A combination of lower corporate tax rates and increased reliance on multinational corporations to produce these surpluses (evidenced by Ireland's widening GDP/GNP gap â the gap that reflects outflows of payments from Irish-based multinational corporations) suggest this much.

Selective Restructuring as the Only Option

Put against the requirement for double-digit current account surpluses in order to deflate the current debt overhang in the Irish economy, the above historical record is not encouraging. Growing out of debt is unlikely to be a sustainable strategy for Irish economy.

The traditional tool-box for dealing with balance sheet recessions includes:

- Growth-supporting external demand

- Availability of cheap investment financing from abroad

- Devaluation-driven improved cost competitiveness

- Deep and swift institutional reforms

- Significant excess capacity for absorption of FDI

Hardly any of the above tools are available to Ireland today.

From this vantage point, restructuring of Irish debts appears to be no longer a policy choice, but a policy necessity. The only remaining question, therefore, is how such restructuring can be configured to minimise adverse effects on the Irish economy.

Given the analysis above, it is clear that the options available to Ireland are:

- Option 1: Restructure official government debt, which is expected to peak at circa 116 per cent of GDP in 2013â2014

- Option 2: Restructure banking sector debts, especially those that represent quasi-governmental liabilities, such as the promissory notes to the Irish Bank Resolution Corporation (IBRC, formerly Anglo Irish Bank), amounting to under â¬30 billion

- Option 3: Restructure household debt

- Option 4: Restructure private corporate debt

Option 4 can be ruled out from the start as it will constitute a market-distorting support for incumbent enterprises. In addition, corporate debt restructuring can be dealt with through both normal liquidation and receivership processes. Furthermore, absent independent monetary policy capacity, restructuring corporate debts in a systemic fashion will have the most adverse impact on the banking sector balance sheets and will lead to significant debt transfers from the private sector to the Exchequer. It is perhaps revealing to note that the Irish government's approach to resolving the banking crisis to date, exemplified by NAMA, attempted exactly this type of restructuring with NAMA purchasing only business loans related to land, development and property investments.

Option 1, while attractive from the fiscal short-term sustainability point of view, carries substantial costs for any Exchequer that is running deep (greater than 1â2 per cent) structural deficits. The requirement for securing external funding to finance gradual adjustments to fiscal deficits means that this option is de facto shut for Ireland.

This suggests that the only two options open for Ireland are Options 2 and 3: restructuring of some banking sector debts and some household debts. The two options are not only feasible, they are actually complementary. This complementarity implies an overall reduced cost of undertaking such restructuring and is driven by the fact that much of the household debt in Ireland is held on domestic banks' balance sheets. Further complementarity is implied by the fact that some of the banking sector debts are directly linked to the government debt â via the promissory notes and NAMA bonds which have been used as collateral for borrowings from the Central Bank of Ireland and the ECB. In other words, restructuring banking sector debts by reducing sector liabilities to external lenders will free resources to draw down some of the assets written against the households and the Exchequer.

The upside to such a drawdown is to reduce the probability of future defaults by the households and to bring loan-to-value (LTV) ratios closer to the level where any foreclosures that might still arise will be carried out at no loss to both the banks and the households. Core benefits, however, are much broader. Restructuring current household debt levels will reduce the overall rates of mortgage default and will simultaneously compensate households for the greater burden of recent banks bailouts and public debt increases.

Mortgages arrears and pressures on household budgets arising from the income and wealth effects of increasing costs of mortgage financing and the continued deterioration in asset values in the Irish property sector are immense. Per the latest data available to us, in Quarter 3 of 2011 there were 773,420 outstanding mortgages in Ireland. Of these, 62,970 mortgages were in arrears more than 90 days, up 55.6 per cent on same period a year ago. In addition, 36,376 mortgages were ârestructured' but are currently âperforming' â in other words, paying at least some interest. Adding together all mortgages in arrears and repossessions, plus those mortgages that were restructured but are not in arrears yet, 100,230 mortgages (13 per cent of the total), amounting to â¬18.3 billion (or 16 per cent of the total outstanding mortgage amount), are currently at risk of default, are defaulting or have defaulted. Given the trend to date, we can expect that by the end of 2011 there will be some 107,000â110,000 mortgages in distress in Ireland. By the end of 2012 this number may rise to over 161,000 or some 21 per cent of the total mortgage pool in the country. When considered in the light of demographic distribution and vintages, mortgages that are likely to be in arrears around the end of 2012/the beginning of 2013 can account for up to 30 per cent of the total value of mortgages outstanding. This is a simple corollary of the fact that the mortgage crisis is now impacting most severely families in their 30s and 40s, with more recent and, thus, larger mortgages signed around the peak of the property bubble. These households are facing three pressures in today's environment.

Firstly, they are experiencing above-average unemployment and income pressures. Per the Quarterly National Household Survey, in Quarter 2 of 2011, the unemployment rate for persons aged 25â34 was 16.5 per cent and the unemployment rate for those aged 35â44 was 12.4 per cent; both well ahead of the 8.95 per cent average unemployment rate for older households. By virtue of being more concentrated in the middle class earning categories, they are also facing higher tax burdens than their lower earning younger and more asset rich older counterparts.

Secondly, they are facing higher costs of living, further depressing their capacity to repay these mortgages. In September 2011, the prices of petrol and diesel were some 15 per cent above their levels a year previously, and bus fares were up 10.8 per cent. Since the time these families bought their houses (circa 2005â2007), primary and secondary education costs increased 21â22 per cent, and third level education costs rose 32 per cent. On average, larger families require greater health spending, the cost of which rose 16 per cent above 2005â2007 levels. The three categories of costs described above comprise circa 20 per cent of the total household budget for an average Irish household and above that for mid-aged households with children.

Thirdly, as their disposable incomes shrink and mortgage costs rise (mortgage-related interest costs are up 17.2 per cent year on year and 11 per cent on 2006), the very same households that are hardest hit by the crisis are also missing vital years for generating savings for their old age pension provisions and the most active years for entrepreneurship and investment.

In short, courtesy of the crisis and the government policy responses to it to date, Ireland already has a âlost generation' â the most economically, socially and culturally productive one. And this generation is now at the forefront of the largest homemade crisis we are facing â the crisis of mortgage defaults and personal bankruptcies. Against this backdrop, the forthcoming Personal Bankruptcies Bill should form a cornerstone of the government's policy.

Bringing household debt to sustainable (growth-supportive) levels in the case of Ireland implies a write-down of circa â¬40â50 billion and can be financed via a direct write-down of the banks' borrowings from the Central Bank of Ireland. In addition, restructuring bank-held government promissory notes to zero coupon 30-year notes will achieve Exchequer savings of circa â¬44â50 billion over the ten years' horizon, depending on the various estimates of the total cost of these notes financing. Finally, taking a direct write-down of 20â25 per cent of Irish banks' borrowings from the ECB will allow for the write-downs of the mortgage debts to the scenario that would bring them in line with the situation where the maximum extent of the current negative equity for primary residences will be no larger than 15 per cent. The combined measures will reduce the overall debt levels of the Irish Exchequer closer to more sustainable 80 per cent of GDP levels (relative to 2010â2012 GDP) and household debts to 90 per cent of GDP.

In the current global economic environment and given the severity of the total real economy debt overhang in Ireland, the above restructuring, which does not involve any non-banking sector participation by private investors or public debt holders, is the lowest cost feasible solution for the crisis. Given the extremely low probability of the Irish economy being able to achieve sutained levels of growth that would be required to âgrow out' of the current debt crisis, it is virtually inevitable that some debt restructuring will take place sooner or later. The longer such a restructuring is delayed, the more severe will be the cumulative losses sustained by the economy in the periods prior to the restructuring and the weaker will be the economy to re-start growth post-restructuring. It is, therefore, imperative that the Irish government leads the markets with a concerted policy response designed to reduce our real economy's debt overhang.